Journal Name: Scholar Journal of Applied Sciences and Research

Article Type: Research

Received date: 09 October, 2018

Accepted date: 25 October, 2018

Published date: 05 November, 2018

Citation: Elheky MA (2018) Hedging in Scientific and Social Texts: A Comparative Analysis of Business and Social Texts. Sch J Appl Sci Res. Vol: 1, Issu: 8 (10-19).

Copyright: © 2018 Elheky MA. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Hedging is a significant resource for academics in anticipation of the reader’s possible rejection of their propositions. Little is known about how hedging is expressed or the functions it serves in different disciplines or genres. English for Specific Purposes (ESP) students are often advised to avoid hedges and to adopt a detached style in their writings. The ability to hedge statements appropriately is essential to effective academic success. In this paper, there is an exploration of the importance and frequency of hedges in scholarly articles in two different disciplines (business and social). It presents the results of a review of 40 scholarly articles, discussing the importance, frequency and realization of hedges in both business and social articles. Thirty business and thirty social articles are selected from ProQuest database and compared to identify the frequency of hedges used in both kinds of texts. The results show that it is the social texts which are mostly frequented according to the use of hedges in comparison with business texts. This study can, therefore, make an important contribution to the understanding of the practical reasoning and persuasion in business and social writing.

Keywords

Hedging, Scientific Texts, Social Texts, Business Texts, Genre.

Abstract

Hedging is a significant resource for academics in anticipation of the reader’s possible rejection of their propositions. Little is known about how hedging is expressed or the functions it serves in different disciplines or genres. English for Specific Purposes (ESP) students are often advised to avoid hedges and to adopt a detached style in their writings. The ability to hedge statements appropriately is essential to effective academic success. In this paper, there is an exploration of the importance and frequency of hedges in scholarly articles in two different disciplines (business and social). It presents the results of a review of 40 scholarly articles, discussing the importance, frequency and realization of hedges in both business and social articles. Thirty business and thirty social articles are selected from ProQuest database and compared to identify the frequency of hedges used in both kinds of texts. The results show that it is the social texts which are mostly frequented according to the use of hedges in comparison with business texts. This study can, therefore, make an important contribution to the understanding of the practical reasoning and persuasion in business and social writing.

Keywords

Hedging, Scientific Texts, Social Texts, Business Texts, Genre.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, a growing interest has been noticed in genre-based language studies. Genres are kinds of spoken and written discourse systematized by a discourse community. Each genre has distinctive features. Such features can be linguistic, paralinguistic, contextual, and pragmatic.

Hedging is a typical feature of academic writing. Hedging is a mechanism that can be used to manage attitude, preposition, and information within a piece of writing. Hedging involves using a tentative language to distinguish between facts and claims and in case that writers are not perfectly certain about the facts they convey such as “it appears likely that” or “arguably” [1]. Hedging is essential in academic writing. Hedging is also used to maintain objectivity. Objectivity is usually linked to the credibility of the writer. Using hedging or avoiding it comes to be an art. Inappropriate use of hedging might violate the written paper.

The common belief is that academic writing, especially scientific papers, is fact-based [2]. It is intended to convey facts and actualities. However, academic writing is currently perceived to adopt a significant feature; the concept of hedging. Hedging is used in varying degrees in genres. It is less apparent in scientific texts than humanistic texts [3]. Certainty is more present in scientific texts than humanistic ones. Academic genres require writers to take the expected audience into account and to have an insight about their background knowledge and reactions to the text [4].

The concept of hedging is a complex research area within the areas of linguistics, pragmatics, semantics, and philosophy. Hedging is defined differently in these areas. In pragmatics, hedging is associated with politeness, mitigation, and vagueness. A hedge can be defined as a strategy that describes a preposition or as one of the lexicosyntactical elements that is utilized to modify a preposition [5]. The convention now is that a certain degree of hedging is used, and it corresponds to an established style of writing in English.

Based on the literature, hedging denotes interpretations and allow writers to express their attitudes to the actuality of the statements they accompany, thereby giving unproven claims warily and indecisive assertions. Yet, very little is known about the function of hedging and how it is expressed in different genres. A considerable amount of research has been conducted on scientific texts such as medicine, biology, engineering texts, but still a less-focused research effort is made on business texts. According to the nature of social texts, it appears that hedging should be used more in that genre of texts rather than business texts. No much evidence can be found in literature to prove this. This study aims to shed light on the frequency of hedges in both business and social texts.

Furthermore, some studies proposed that hedging appears to be unobserved by L1 and L2 readers and this was called “Lexical Invisibility Hypothesis”, suggested by Low [6]. He mentions that respondents of a questionnaire do not notice boosters (such as clearly and obviously) and hedges in most of the questions of a questionnaire.

Consequently, learners are not aware of hedges as a characteristic of academic writing and of the functions they perform in the relationship between the writer, the reader, and context. How writers make a distinction between facts and opinions and how they evaluate certainty is essential in the meaning of academic texts.

Particularly speaking, this paper seeks to answer two questions:

- How frequently hedging is used in business and social texts?

- What are the similarities and differences between business and social texts with regard to hedging frequency?

A typical function of language is to establish cultural communication. There are cross-cultural variations and such variations establish a pragmatic awareness of discourse communities. Pragmatic awareness is to enhance learners’ sensitivity to such differences. Teaching the different types of writing is crucial as it makes learners aware of the notion that writing in their mother tongue differs from that of the target language they are pursuing [7]. Pragmatic awareness assists in deciding upon the paralinguistic choices. This competence plays a role in knowing how the text is suitable to the style of writing in the second language.

Recent researches in written texts denote an increasing interest in the interaction between the reader and the writer. A considerable number of studies concentrated on textual analysis, organizational patterning, and specific text features such as hedging, modalities, and reporting verbs [8]. There is a common belief that scientific texts are based on factual information, and caution and scientific honesty are present in scientific community. Social authors may wish to make cautious statements by using statements associated with uncertainty and using a tentative language known as hedges. Through hedging, writers in academic contexts are nicely placed to show whether they are certain or doubtful about their statements and to what extent they are confident of their claims [9]. Through hedging, readers are given some space to adjudge the truth value of the assertion. Examples of hedging include may, assume, unclear, and perhaps.

Hedges are devices that provide a space for negotiation. They manage to give alternative views of the statements. Hedging goes back to a paper introduced by Lakoffs [10] titled “Hedges: A study in meaning criteria and the logic of fuzzy concepts”. The claim of Lakoffs was that the concepts of Natural Languages (NL) can be fuzzy and vague. He rejected the idea of his contemporary logicians that NL concepts are either true or force. The interest of Lakoffs was not centered upon how hedges are employed pragmatically, but he concerned himself with the logical properties of words like quite, greatly, rather, so, too and phrases such as generally speaking and how such words and phrases can make things more or less fuzzy. From that time on, hedging has been pursued in Speech Acts Theory and oral discourse. Hedging was also embraced by language pragmatists and academic discourse analysts.

Definition of Hedging

There has been a little agreement on the term of Hedging. Cabanes [11] defines hedging as a lack of ultimate commitment to what the utterance propositionally conveys. Through hedging, writers attempt to show how their statements are accurate and, simultaneously, they care for saving their faces in case that their judgments undergo any possible falsification. Also, another definition is presented by Hyland [7] that defines hedging as modifiers of the writer’s accountability for the truth value of what he expresses or as descriptors of the weightiness of the information presented and the attitude of the writer towards such information. The rationale beyond using hedging is to imply the meaning of uncertainty for the text and that the author is not sure about what he discusses in the text. This definition implies that hedging is utilized as a way of securing the readers’ acceptance and motivation. Hedging can be used in various linguistic forms such as the conditional statements, verb choice, modifiers, and personal viewpoint statements [12]. This means that hedging is an activity that softens facethreatening as readers are given alternatives and make their own interpretations and this is a sort of politeness towards readers. Also, hedging is a way of qualifying categorical commitment and facilitating discussion” [13]. Hedging is, thus, seen as the device by which the writer can convey his beliefs and subjective viewpoints about his claims.

Jalifafr and Shoostari [14] convey that hedges, with their function as mitigators, are used as a strategy for preserving status that seeks to make the inappropriate speech act a more appropriate one with the speaker’s status in the situation. This means that hedges are used in speech acts to make up for the unsuitability of the speech act that is used in writing or speaking.

Reasons for Hedging

Different reasons have been identified by different researchers for hedging. Below are some of these reasons:

- a) Authors use hedging in order to tone down their utterances and minimize the risk of opposition. This is to avoid scientific imprecision and personal accountability for what is presented [15].

- b) Authors need to inform readers that what they claim is not clear-cut and the final word on the topic. Incomplete certainty does not inevitably mean that there is a vagueness or confusion. Hedges can be considered as techniques for reporting results more precisely. They reflect the real understanding of the writer and can call for a negotiation over the state of knowledge under investigation. The lack of robust evidence and accredited data may make academic writers prone to use hedging as they may not be able to account for stronger claims [16].

- c) Hedging can be used as a positive or negative politeness strategy through which the author tries to be modest and not assuming that he has the powerful knowledge. Hedging is used for rationalization in order to establish a relationship between readers and writers or speakers and listeners as well as securing a certain level of acceptability in the society. As the claim gets a popular acceptance, it can then be reported without hedging [17].

- d) Now, it is the convention to use a certain degree of hedging. Hedging becomes a feature of an established writing style in English [18].

Types of Hedging

Content-Oriented Hedges

Such types of hedges aim to mitigate the connection between the suppositional content and the manner of representing reality. They hedge the correspondence between what the author claims about the world and what the world is perceived to be like [2].

Writer-Oriented Hedges

Such types of hedges are regarded as strategies that intend to protect the writer from what results from conveying his personal commitment. Impersonal constructions such as the passive voice are in place, avoiding straightforward reference to the author [1].

Reader-Oriented Hedges

This type is concerned with the relationship between the reader and the writer. Writers pay attention to the interactional impacts of their statements and entreat the reader as a colleague who is able take part in the discourse with an open mind [19].

Hedging Devices

Hedging can be expressed in more than one way. Jalifafr [20] mentions the following devices as the most common hedging devices: (Table 1)

Table 1: Source: Jalifafr [20]. The most common hedging devices.

| 1 | Introductory verbs: | e.g. look like – seem – appear – indicate – suggest |

| 2 | Certain lexical verbs: | e.g. believe – assume – think |

| 3 | Certain modal verbs: | e.g. may – will – should – could - shall |

| 4 | Adverbs of frequency: | e.g. often – usually – sometimes |

| 5 | Modal adverbs: | e.g. perhaps, probably – clearly – certainly |

| 6 | Modal adjectives: | e.g. certain – probable – possible- definite |

| 7 | Modal nouns: | e.g. assumption – possibility – probability |

| 8 | That clauses: | e.g. it can be suggested that ……, there is a hope that …. |

| 9 | To-clause + adjective | e.g. it may be possible to …, it is significant to…. |

Hedging and Gender

Research on gender differences suggests than females are more concerned with matching, compatibility, and social relationships than males [21], so it is easier to convince them than males.

In their study, Tabrizi [3] examined changes in the attitudes of males and females after reading a hedged text. The study revealed that there are statistically significant differences between the two genders. Females achieved high scores than men because they have shown acceptance of others’ different views and emphasizing with other people. Also, Mazhari [22] claims that women use hedges more than men in order to avoid being wrong in their judgment.

Hedging across Cultures and Languages

Hedging differs from one language to another. Hedging can be noticed in all-natural languages, but using hedges is influenced by the structure of the language. For example, politeness is conveyed differently by English and German speakers [22]. To make requests, English speakers use more hedges than the German ones. English speakers use more hedges as they think that their requests will be regarded as less polite if no more hedges are used.

Also, the use of hedges differs from one culture to another. Conducting a study on commitment and detachment in English and Bulgarian, Varttala [15] noted that commitment is used in Bulgarian higher than its usage in English. English writers use a higher degree of detachment as they are more hesitated in making forward claims and to avoid facethreatening acts.

Furthermore, Swales [18] conveys that French and Dutch students encounter a difficulty in using modal verbs appropriately in English. He claims that students cannot distinguish between the accurate differences between the modal verbs and they are not able to use them frequently as the native speakers.

Empirical Studies

The importance of hedging has been reported by a considerable number of studies. Hedging is utilized to report results, account for findings, make inferences out of evidences, convince readers, and set up interpersonal ties between readers and writers [15]. Despite the significance of hedging, Hyland [7] mentions that very little is known about the use and frequency of hedging in different genres. The study of hedging gives insights into how knowledge is created and how it is tackled by scholars. Scientific writers attempt to persuade their readers of the precision of their claims by using hedged devices of doubt and uncertainty.

Hedging was investigated in scientific writing. Cabanes [11] compared hedging in English and Spanish architecture project descriptions. The study concluded that hedging is used to serve three functions: it expresses politeness towards the audience, it protects the writer from claims that may be wrong, and it implies the degree of precision that the writer considers in his text. Tabrizi [3] conducted a more recent study in which she compared hedging in biology and ELT texts. The study was conducted on (60) research articles and it was concluded that hedges are most frequently used in ELT texts than biology texts. In a study conducted by Hyland [23], around 27 articles on molecular biology published between 1990 and 1995 were examined and it was revealed that modality is a significant way of expressing hedging. Furthermore, Ignacio and Diana [9] studied hedging in three types of research articles; Marketing, Biology and Mechanical Engineering. They found out that hedging is used differently in the three areas.

Also, a further examination by Hyland of the metadiscourse features in seven biology articles revealed that scientists use hedging for two purposes; addressing the intended reader and conveying their personal attitudes towards what they claim [23].

Furthermore, Clemen [24] studied hedging in economic texts to provide evidence that hedges are found in economic texts. He conducted his study on 13 copies of the Economist through three months and the analysis was made on the columns of Economy and Marketing. He found out that hedging is normally used in economic texts and that various hedging devices are employed in the two types of texts, with modals being the most frequently used devices to express hedging.

Also, hedging was investigated within social texts in order to get a picture of how hedging devices is used in that genre. In their study, Salager-Meyer [5] conveyed that social texts are mostly associated with using hedged devices such as the passive voice and probabilities. In a study conducted by Malaskova [25], a comparison was made between research articles in humanities and social sciences in order to notice the similarities and differences in the occurrence of hedges in these two genres. The study concluded that formal and semantic variations appear to exist in hedges employed in linguistics and literary criticism research articles.

Hyland [7] investigated the use of boosters and hedges in mass communication research articles and concluded that boosters are used more than hedges and that mass communication writers are more confident about their claims than writers of biology. In addition, Martin [4] compared the frequency of hedging in Clinical and Health Psychology in English and Spanish research articles and concluded that English research articles involved more protection to the writer’s face than the Spanish research articles.

In academic writing, Mojica [21] investigated Filipino writers’ ways of showing commitment in their English academic papers. The study concluded that modals and probabilities are preferred forms of hedging. In a study conducted by Hyland [7], he concluded that EFL writers tend to use direct and unqualified writing and that stronger models are used as a way of showing commitment. Gries and David [26] studied two hedging expressions in data obtained from contemporary British English. They concluded that hedges are used differently in different genres [1]. Hyland [23] analyzed the use of directives and hedges in published articles, textbooks and second language student’s essays. He concluded that directives are used for different purposes across different branches of Knowledge.

Based on the literature of hedging, it is clear that hedging was studied in the context of scientific texts such as biology, engineering, and architecture. Also, hedging was studied in the context of social texts such as psychology and mass communication. Moreover, hedging was examined through comparative studies such as scientific and humanistic texts and scientific and ELT texts. None of the previous studies investigated hedging in business and social texts in the context of scholarly articles. The previous researchers focused mainly on the abstract parts of the researches rather than the whole body of the research. The intention here is to examine the frequency of hedges in the whole body of the research to understand which kind of texts need more usage of hedges.

Corpus

In order to notice hedges in both business and social texts, 40 scholarly articles were selected. For business articles, 20 business articles were selected. For social texts, 20 social articles were also selected. The articles were selected from the well know and prestigious ProQuest database. The articles selected were published in the period from 2006 – 2011. The articles were chosen randomly, and to secure a sufficient amount of data, the articles that contain more than 3000 words were only selected.

Procedures

The articles on both genres were downloaded from the database. All of these articles were all soft copies and the frequency of hedges were collected. The collection of hedges was made through the QB text analyzer software in the computer in order to reach the frequency of such cautious words. QB text analyzer software is a facility that gives a list of the vocabulary in a sample text. The software can be downloaded from the following link: http://www. brothersoft.com/qb---text-analyzer-31287.html. The number of hedges was counted by the software.

Analysis

(Table 2) The frequency of hedges was analyzed according to Jalifafr’s [20] classification of hedging words:

Table 2: Source: Jalifafr [20]. Classification of hedging words.

| 1 | Introductory verbs: | e.g. look like – seem – appear – indicate – suggest |

| 2 | Certain lexical verbs: | e.g. believe – assume – think |

| 3 | Certain modal verbs: | e.g. may – will – should – could - shall |

| 4 | Adverbs of frequency: | e.g. often – usually – sometimes |

| 5 | Modal adverbs: | e.g. perhaps, probably – clearly – certainly |

| 6 | Modal adjectives: | e.g. certain – probable – possible- definite |

| 7 | Modal nouns: | e.g. assumption – possibility – probability |

| 8 | That clauses: | e.g. it can be suggested that ……, there is a hope that …. |

| 9 | To-clause + adjective | e.g. it may be possible to …, it is significant to…. |

The frequency of words was found by the QB text analyzer software according to the above mentioned classification. Verbs were searched in their different forms; for example, the verb “appear” with all its different forms (appears – appeared – appearing) were considered.

The analysis moved as follows: the first category in the classification (Introductory verbs) were analyzed and the frequency of these words were found: (e.g. seem, appear. Think, doubt. Look like). The analysis then moved to the other categories respectively and the frequency of these hedges were calculated for the nine categories. The hedges of the nine categories were obtained in scientific texts and they were also obtained in the social texts. The next step was to estimate the overall usage of each hedge in each category. For example, the modal adverb “certainly” was used 20 times in scientific texts and 45 times in social texts and the same process was conducted for all hedging words within the nine categories. The results were shown in tables.

Results of the Study

This research is descriptive nature. Data collection is mainly based on a simple frequency count. Determining the differences in hedging devices in business and social texts from (40) scholarly articles is made employing Jalifafr’s [20] classification. The nine hedging devices are examined in each type of texts (20 scholarly articles for each type) and the QB-text analyzer was used to find the frequency of the words in each group.

The Frequency of Introductory Verbs for each Group

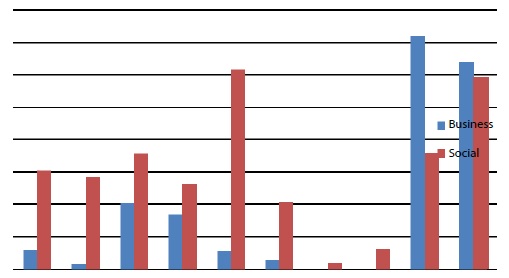

(Table 3) The first group in this classification as shown in table 4.1 is related to introductory verbs. This group consists of ten introductory verbs. Each verb is searched once for each article in business group and then each article in social group. For example. The verb “appear” with its all different forms (appeared, appearing, appears), as shown in table 4.1., is used 168 times in business articles and 264 times in social articles. The verb “believe” again with its all different tense forms (believed, believes, believing) is used 28 times in business articles and 208 times in social articles. As it is clear from the total results for the frequency of each verb, all of the introductory verbs are used much more frequently in social articles than in business articles except two verbs: indicate and suggest. These two introductory verbs are used much more frequently in business than in social articles (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Frequency of Introductory Verbs for each Group.

Table 3: The Frequency of Introductory Verbs for each Group.

| Text Type | Introductory Verbs | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seem | Tend | Likely | Appear | Think | Believe | Doubt | Sure | Indicate | suggest | |

| Business | 60 | 16 | 204 | 168 | 56 | 28 | 0 | 0 | 720 | 636 |

| Social | 304 | 284 | 356 | 264 | 616 | 208 | 20 | 64 | 360 | 592 |

The Frequency of Certain Lexical Verbs for each Group

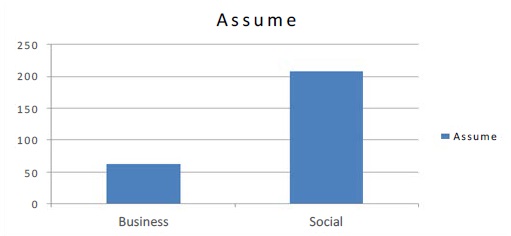

(Table 4) The second group in this classification is related to lexical verbs which consist only of one verb: assume. This verb, as it is clear from table 4.2., is used 62 times in business articles and 208 times in social articles. Again, in this group, the business articles are less frequented than the social ones (Figure 2).

Figure 2: The Frequency of Certain Lexical Verbs for each Group.

Table 4: The Frequency of Certain Lexical Verbs for each Group.

| Text Type | Certain Lexical Verbs |

|---|---|

| Assume | |

| Business | 62 |

| Social | 208 |

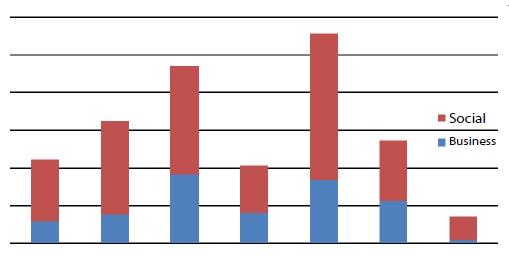

The Frequency of Certain Modal Verbs for each Group

(Table 5) The third group is related to certain modal verbs. It consists of seven modal verbs. Each verb has been searched for separately and it is clear from table 4.3. Again, modal verbs like the other verbs in table 4.2 and table 4.1 are much more frequented in social articles than in business ones. For example, the modal verb may has been used 912 times in business articles and 1436 times in social articles. Also, modal verb can has been used 840 times in business articles and 1944 times in social articles. Considering the total usage of all modal verbs in this group, it is valid that all modal verbs have been used more frequently in social than in business articles (Figure 3).

Figure 3: The Frequency of Certain Modal Verbs for each Group.

Table 5: The Frequency of Certain Modal Verbs for each Group.

| Text Type | Certain Modal Verbs | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Will | Would | May | Might | Can | Could | must | ||

| Business | 288 | 388 | 912 | 400 | 840 | 564 | 44 | |

| Social | 824 | 1236 | 1436 | 632 | 1944 | 796 | 316 | |

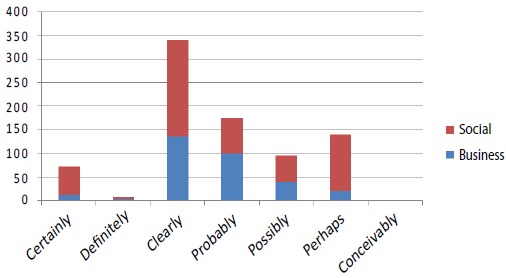

The Frequency of Modal Adverbs for each Group

(Table 6) The fourth group in this classification is related to modal adverbs. It consists of seven adverbs. As clear from the total results of the frequency of these words, modal adverbs are more frequently used in social than in business articles. For example, possibly is used 40 times in business articles and 56 times in social articles. It shows that this verb is more frequented in business rather than in social articles. However, the modal adverbs definitely and conceivably are used equally in each type of texts. Definitely is used 4 times is each type of articles and conceivably is used zero times (Figure 4).

Figure 4: The Frequency of Modal Adverbs for each Group.

Table 6: The Frequency of Modal Adverbs for each Group.

| Text Type | Modal Adverbs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certainly | Definitely | Clearly | Probably | Possibly | Perhaps | Conceivably | |

| Business | 12 | 4 | 136 | 100 | 40 | 20 | 0 |

| Social | 60 | 4 | 204 | 76 | 56 | 120 | 0 |

The Frequency of Adverbs of Frequency for each Group

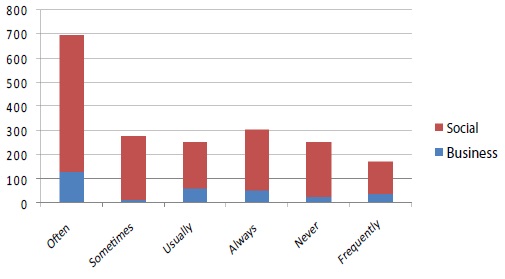

(Table 7) The fifth group in this classification is related to adverbs of frequency. This group consists of only six verbs of frequency. All of them have been used much more frequently is social articles than in business ones. For example, often has been used 128 times and 568 times in business and social articles, respectively. Always has been used 52 in business articles and 252 in social articles. Frequently has been used 36 times in business articles and 136 times in social ones. In the fifth group (modal adverbs), it is again that the social articles have the most frequently hedging words in comparison to business articles (Figure 5).

Figure 5: The Frequency of Adverbs of Frequency for each Group.

Table 7: The Frequency of Adverbs of Frequency for each Group.

| Text Type | Adverbs of Frequency | Often | Sometimes | Usually | Always | Never | Frequently |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Business | 128 | 12 | 60 | 52 | 24 | 36 |

| Social | 568 | 264 | 192 | 252 | 228 | 136 |

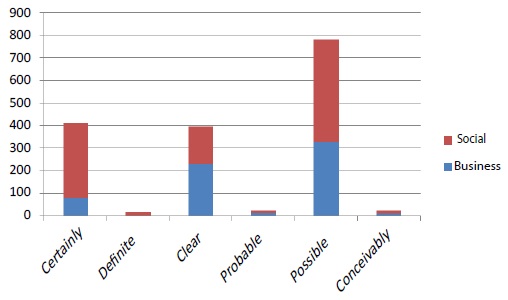

The Frequency of Modal Adjectives for each Group

(Table 8) The sixth group is related to modal adjectives. Like modal adverbs, this group consists of six modal adjectives. Unlike modal adverbs which were all more frequented in social than in business articles, the adjectives for the same modal adverbs were in different situation according to their usage of hedging words. Three of them, certain, definite, and possible were more frequent in social rather than in business articles. For example, certain has been used 80 times in business articles and 332 times in social articles. However, the other two adjectives clear and probable were both used more frequently in business articles than in social ones. Clear has been used 228 times in business articles and 168 times in social ones and probable has been used 16 times in business articles and 8 times in social ones. Conceivable has been used equally in each article type: 12 times in each article type. It then seems that modal adjectives have been used equally in each article type (Figure 6).

Figure 6: The Frequency of Modal Adjectives for each Group.

Table 8: The Frequency of Modal Adjectives for each Group

| Text Type | Modal Adjectives | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Certain | Definite | Clear | Probable | Possible | Conceivable | |

| Business | 80 | 4 | 228 | 16 | 328 | 12 |

| Social | 332 | 16 | 168 | 8 | 452 | 12 |

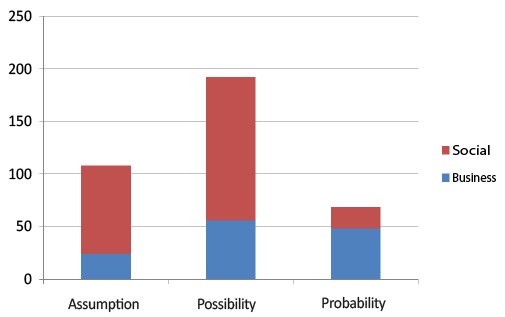

The Frequency of Modal Nouns for each Group

(Table 9) The seventh group in this classification is related to modal nouns. This group consists of three modal nouns: assumption, possibility, probability. Two of them: assumption and possibility have been used more frequently in social articles rather than in business ones. Assumption has been used 24 and 84 times and possibility has been used 56 and 136 times in business and social articles, respectively. However, probability has been more frequently used in business articles than in social ones. It has been used 48 times in business, but only 20 times in social articles. So, as it is clear, again here in the seventh group, that hedges are more frequent in social articles than the business ones (Figure 7).

Figure 7: The Frequency of Modal Nouns for each Group.

Table 9: The Frequency of Modal Nouns for each Group.

| Text Type | Modal Nouns | Assumption | Possibility | Probability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Business | 24 | 56 | 48 |

| Social | 84 | 136 | 20 |

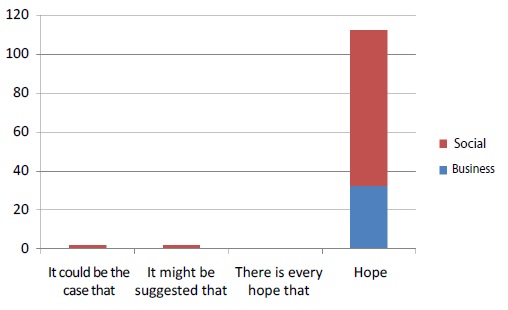

The Frequency of That-Clauses for each Group

(Table 10) The eighth group in this classification is related to that-clause. Inside this group, there are three kinds of that-clause and the noun “hope”. The first one, “it could be the case that”, has been used in none of business articles and used 2 times in social articles. The second one, “it might be suggested that”, has been used in none of business articles and used 2 times in social articles. The third one, “there is every hope that”. has been used none in both of article types. However, the word hope has been much more frequently used in social articles than in business ones: 32 times in business articles and 80 times in social articles. It is obvious that social articles need more hedging words whenever it comes to claim a statement, that’s why fuzzy words such as hope has been used much more in social than in business articles (Figure 8).

Figure 8: The Frequency of That-Clauses for each group.

Table 10: The Frequency of That-Clauses for each Group.

| Text Type | That-Clauses | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| It could be the case that | It might be suggested that | There is every hope that | Hope | |

| Business | 0 | 0 | 0 | 32 |

| Social | 2 | 2 | 0 | 80 |

The Frequency of Adjective + To-Clause for each Group

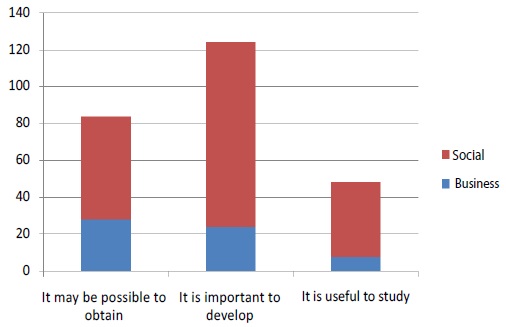

(Table 11) The last group in this classification is related to adjectives + to-clauses. It consists of three kinds of clauses and all of them are used more frequently in social articles than in business ones. For example, “it may be possible to obtain” has been used 28 and 56 times in business and social articles, respectively. Also, “it is important to develop” has been used 24 and 100 times and “it is useful to study” has been used 8 and 40 times in business and social articles, respectively. Again in the last group, hedging words have been used much more frequently in social articles rather than in business ones (Table 12) (Figure 9,10).

Figure 9: The Frequency of Adjective + To-Clause for each group.

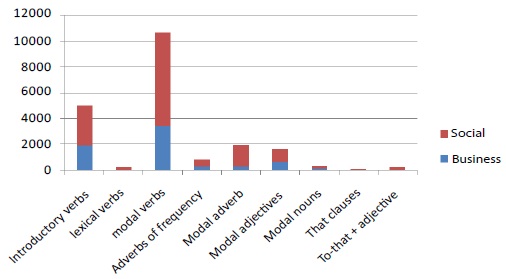

Figure 10: The overall Frequency of each Category in each Text Type.

Table 11: The Frequency of Adjective + To-Clause for each Group.

| Text Type | Adjective + To-Clause | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| It may be possible to obtain | It is important to develop | It is useful to study | |

| Business | 28 | 24 | 8 |

| Social | 56 | 100 | 40 |

Table 12: The overall Frequency of each Category in each Text Type.

| Text Type | Categories | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Introductory verbs | lexical verbs | modal verbs | Adverbs of frequency | Modal adverb | Modal adjectives | Modal nouns | That clauses | To-that + adjective | |

| Business | 1888 | 62 | 3436 | 312 | 312 | 668 | 128 | 32 | 60 |

| Social | 3068 | 208 | 7184 | 520 | 1640 | 988 | 240 | 84 | 196 |

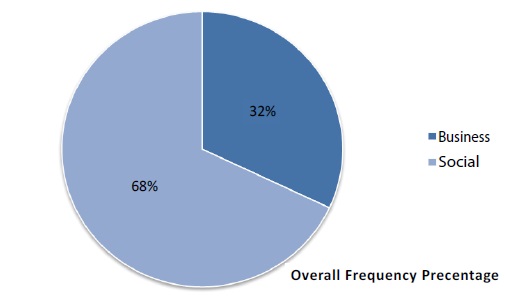

The Overall Percentage of Hedging Frequency

(Figure 11)

Figure 11: The Overall Percentage of Hedging Frequency.

Discussion of Results

Based on the findings of the comparison between hedging in business and social scholarly articles in the abovementioned part, it was the social group that had the most usage of hedging words in the whole body of texts. This finding corresponds with the literature that hedging is used differently in each genre such as the studies of Ignacio and Diana [9], Hyland [7], and Salager-Meyer [5].

That hedges are used most frequently in social texts than business texts were supported by a number of studies such as Clemen [24] and Ignacio and Diana [9]. The abundant use of hedges in social texts was also supported by the studies of Malaskova [25] and Salager-Meyer [5].

The use of hedging in academic writing is apparent and factual and this corresponds to the findings of Mojica [21], Gries and David [26], Hyland [7] and Hyland [23].

Among the nine groups of hedging, modals and probabilities are the most favored ways of expressing hedging and this corresponds with the what Mojica [21] conveyed that modals and probabilities are the most frequently used devices of hedging. The finding that probabilities are mostly used in social texts is supported by Salager-Meyer [5].

The study also reveals that hedges are used more frequently than boosters in both types of texts and this finding corresponds with the study of Low [6] in which he conveyed that hedges have a preference over boosters.

These findings are justifiable. The first justification could be the nature of the social sciences. When dealing with business articles as belonging to the scientific genre, there is no much doubt about the findings of the research. For example, if a research is conducted on medicine, sentences like “this medicine might be helpful for skin cancer” or “this drug may work on you if you want to treat your sore throat” cannot be used. As it is obvious, all these doubts can lead to the fact that no one will be able to use these drugs in the future because they can’t risk on their health. However, when dealing with social sciences, it cannot be sure about the results of researches on behaviors as social sciences try to explain and account the different behavioral patterns and such patterns are complex and vary from one to another. So, it is clear that words such as seem, may, might, etc. are going to be used frequently in social sciences. This finding is supported by Hyland [7], Hyland [23], Tabrizi [3], Ignacio and Diana [9], and Malaskova [25].

The second justification can be due to cultural differences. In literature review, differences in hedging in cultures and languages have been noticed by [22]. Some languages due to their nature use a lot of hedges in their texts. For example, English authors use more hedges than German authors. Since most of the researches have authors with different nationalities, it is obvious that the frequency of hedging words is going to be different due to the authors’ nationalities and this corresponds with what Varttala [15] said. Considering the nature of the texts too, the frequency of the hedging words is going to be much more in social texts with English writers rather than in social texts with German authors.

Conclusion

The goal of this paper was to answer the question of how frequently hedging is used in business and social articles. A number of scholarly articles from each genre was selected and analyzed according to Jalifafr’s classification of hedging devices that included nine categories: introductory verbs, certain lexical verbs, certain modal verbs, adverbs of frequency, modal adverbs, modal adjectives, modal nouns, that-clauses and to-clause adjective. The frequencies of nine categories of hedges were calculated and presented in tables.

The findings of the study revealed out that hedging is most frequently used in business articles than in social ones. In all of comparisons, it was the social articles that had the most frequency of the hedging words. Among the nine models within groups, it was the third model (modal verbs), both in business and social groups, which had the highest usage of the frequency of hedging words. This result can clarify the point that social writers apply more hedges than the business writers. In business papers, authors prefer to show their stance with much more confidence. In social papers, authors cannot talk so certainly about the results because they are dealing with human behaviors and it is impossible to guarantee a result so firmly, so, they fail to make watertight predictions or conclusions. Learners should understand the writer’s true stance relating to the topic being discussed. They should know how certainly the authors are expressing their ideas. A clear awareness of the pragmatic impact of hedges and an ability to recognize them in texts is crucial to the acquisition of a rhetorical competence in any discipline.

There is no references