Journal Name: Journal of Cardiovascular Disease and Medicine

Article Type: Research

Received date: 31 May, 2018

Accepted date: 14 June, 2018

Published date: 26 June, 2018

Citation: Porto CM, Silva VL, Filho BM, Leão RCH, Souto CCL, et al (2018) Association between Vitamin D Deficiency and Cardiovascular Risk Factors in Elderly. J Cardiovas Disea Medic 1:1 (43-52).

Copyright: © 2018 Porto CM, et al. This is an openaccess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

It is important to identify earlier cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly due to cardiovascular aging and associated chronic diseases. In addition to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, vitamin D deficiency is also a new risk factor. To evaluate the association between vitamin D deficiency with cardiovascular risk factors in elderly patients in outpatient cardiology clinics was performed Cross-sectional study. Clinical data were collected from patients aged over 60 years in cardiology clinics of UFPE, from November 2015 to March 2016. The variables were independent, vitamin D deficiency and dependent on age, sex, education, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, renal failure, dementia, stroke, dyslipidemia, depression, smoking, alcoholism, obesity, andropause, coronary artery disease, left ventricular hypertrophy or impaired left ventricular function and cardiac arrhythmia. They were used the chi-square test Person and, when necessary, Fisher’s exact test. Among the 137 elderly, was identified 91.2% were hypertensive; 35.0% with definite or possible coronary artery disease, 27.7% with cardiac arrhythmia or left ventricular hypertrophy. 65% of the elderly were deficient in vitamin D. More vitamin D deficiency risk were male gender, age ≤ 70 years, smokers, obese, diabetic, with scores compatible with dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary heart disease, ventricular hypertrophy left or reduction in left ventricular function. There was a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly, strongly associated with smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy or impaired left ventricular function.

Keywords

Vitamin D, Aged, Risk.

Abstract

It is important to identify earlier cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly due to cardiovascular aging and associated chronic diseases. In addition to traditional cardiovascular risk factors, vitamin D deficiency is also a new risk factor. To evaluate the association between vitamin D deficiency with cardiovascular risk factors in elderly patients in outpatient cardiology clinics was performed Cross-sectional study. Clinical data were collected from patients aged over 60 years in cardiology clinics of UFPE, from November 2015 to March 2016. The variables were independent, vitamin D deficiency and dependent on age, sex, education, ethnicity, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism, renal failure, dementia, stroke, dyslipidemia, depression, smoking, alcoholism, obesity, andropause, coronary artery disease, left ventricular hypertrophy or impaired left ventricular function and cardiac arrhythmia. They were used the chi-square test Person and, when necessary, Fisher’s exact test. Among the 137 elderly, was identified 91.2% were hypertensive; 35.0% with definite or possible coronary artery disease, 27.7% with cardiac arrhythmia or left ventricular hypertrophy. 65% of the elderly were deficient in vitamin D. More vitamin D deficiency risk were male gender, age ≤ 70 years, smokers, obese, diabetic, with scores compatible with dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary heart disease, ventricular hypertrophy left or reduction in left ventricular function. There was a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly, strongly associated with smoking, obesity, diabetes mellitus, dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease and left ventricular hypertrophy or impaired left ventricular function.

Keywords

Vitamin D, Aged, Risk.

Introduction

In addition to the cardiovascular risk factors common to individuals, in general, such as biological, lifestyle, metabolic and socioenvironmental, as regards the elderly population, are also the gradual reduction of cardiovascular reserves and the decline of functions endocrine diseases, increasing the risk of cardiovascular diseases [1].

Due to the modifications of the cardiovascular system inherent to aging, as well as the chronic diseases associated with this system, the adoption of a healthy lifestyle, with earlier identification and reduction of cardiovascular risk factors, was encouraged [2].

The literature is extensive, reporting an association between vitamin D deficiency with a higher prevalence of cardiovascular endpoints such as angina, acute myocardial infarction (AMI), heart failure (HF) and peripheral vascular disease, compared to individuals with higher levels of vitamin D. In addition, large prospective studies have also demonstrated this association between calcitriol deficiency and increased cardiovascular risk [3-7], as well as associated with higher risk of death [6,8,9] and a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis [10] due to the probable anti-inflammatory and antiatherogenic mechanisms of this vitamin, suggesting that vitamin D deficiency is a cardiovascular risk factor [11].

The 2010 Consensus for Vitamin D Nutrition Guidelines Consensus noted that more than 50% of older people worldwide do not have satisfactory levels of vitamin D [12].

High concentrations of vitamin D3 predict thirteen fewer years of mortality and cardiovascular disease (CVD) incidence [13]. A recent July 2015 study evaluating the longevity of centenarians and their relationship with vitamin D levels, comparing with patients with early AMI and healthy individuals from the same age group, found that centenarians had higher levels of vitamin D than normal adults and concluding that these levels of vitamin D because they confer physiological advantages and better cardiovascular function, are associated with successful aging [14].

This study has as an object the association between vitamin D deficiency and sociodemographic and cardiovascular risk factors in the elderly attended at a cardiology outpatient clinic.

Materials and Methods

It is an Epidemiological Study, Cross-Sectional and Analytical. The study sites were the Center of Attention to the Elderly of the Federal University of Pernambuco (UFPE) and the cardiology outpatient clinic of the UFPE Hospital das Clinicals. The selection of the population of this study was carried out from the analysis of records of the elderly, attended in these services, from November 2015 to March 2016.

The adopted age cut obeyed the Brazilian legislation, regardless of the health status of the person, according to Law No. 8.842 of 1994 [15]. Assuming a prevalence of 80% of vitamin D deficiency among the elderly, a drawing effect equal to one, the sample size equaled 137 records, corresponding to a 95% test power.

For inclusion in the study, it was admitted that they should be medical records of elderly patients, who presented for routine cardiac evaluation, attended by the researcher in a cardiology outpatient clinic, by referral or spontaneous demand, regardless of sex and motor restrictions.

The exclusion criterion was absence of record of all parameters of interest in the medical record or record of the elderly presenting a state of health compromised with indication of hospitalization, at the cardiological examination.

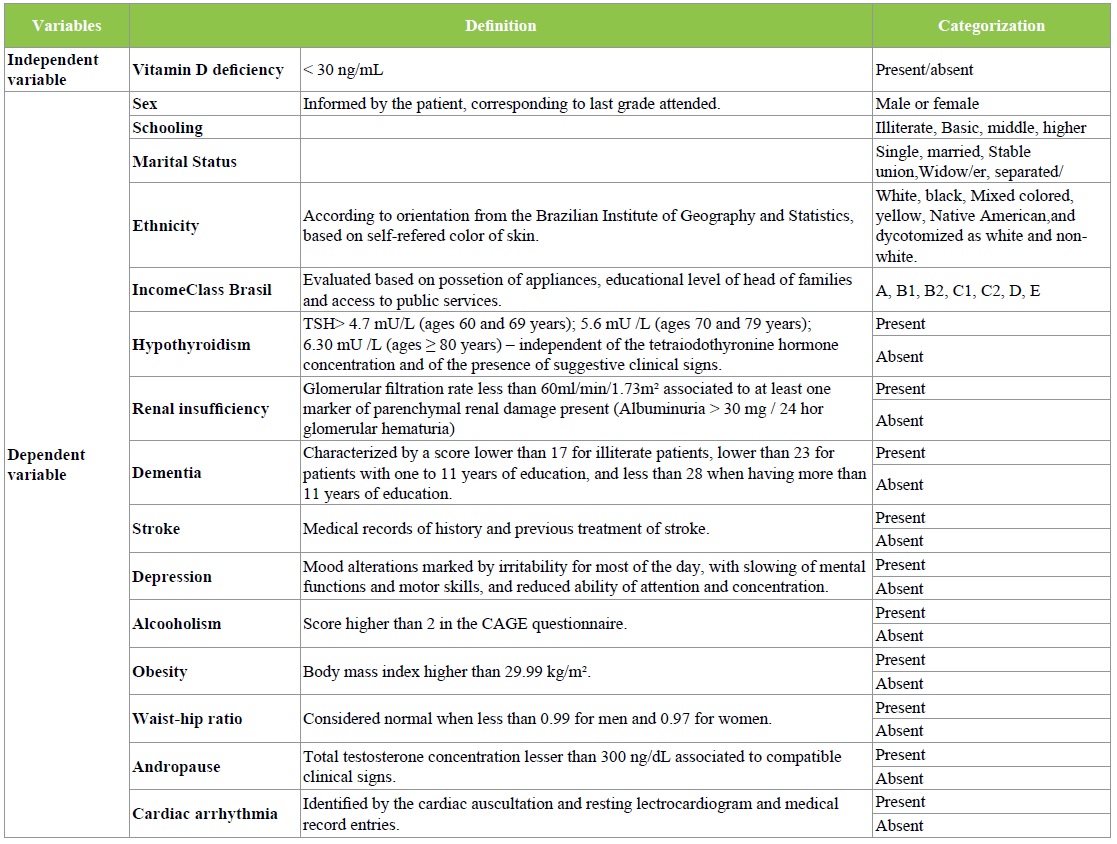

The study variables are characterized according to Table 1.

Table 1: Independent and dependent variables of the study, Hospital das Clínicas, Recife, 2015-2016.

The instruments of data collection were the copy of the protocol of cardiological investigation used in the ambulatory of Cardiology of the places of study, plus the Mental State Mini-Exam and the Geriatric Depression Scale. After approval of the research project by the Ethics Committee for Research on Human Beings, data collection consisted of requesting the File and Statistical Service of the study sites the patient records that obeyed the inclusion criteria of this study.

A database with all the dependent variables and the independent variable of this research, recorded in the medical records, using the Epi7 program, version 7.1.5.2, of the WHO was elaborated. The data were analyzed with the IBM/SPSS Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 20.0.

Hypothyroidism, renal insufficiency, dementia, cerebrovascular accident, cardiac arrhythmia, coronary artery disease (CAD), left ventricular hypertrophy, or reduction of left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) were considered as dependent variables: gender, education, marital status, ethnicity, depression, alcoholism, obesity, andropause, as well as the serum concentration of 25 hydroxyvitamin D was admitted as an independent variable measured by the chemiluminescence method (Architect Abbott®).

All variables on nominal or ordinal scales were summarized by absolute and relative frequency distributions, with subsequent dichotomization in order to integrate the inferential analyzes. In the bivariate analysis, Pearson’s Chi-square test and, when necessary, the Fisher’s exact test were used to test the association between the variables. All conclusions were taken using the significance level of 5%.

Ethical Considerations

This research obeyed the determinations of Resolution Nº 466, of 2012, of the National Health Council, which governs research involving human beings and was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Pernambuco under CAAE nº 47317715.6.0000.5208.

Data collection was authorized through the letters of consent from the Center for Elderly Care and Management of the Hospital das Clinicals of the Federal University of Pernambuco. The researcher undertook to maintain the confidentiality of the data and the identification of the patients in any publication.

Results

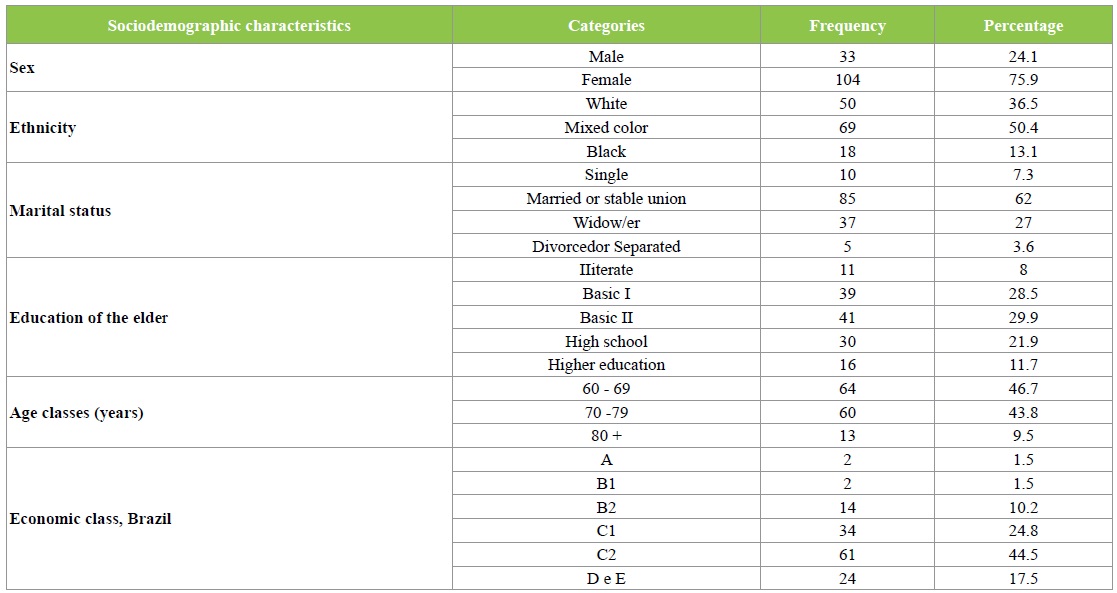

Analyzing the characteristics of the 137 elderly people surveyed, according to the data presented in Table 1, we found that 75.9% of them are female, 50.4% had brown skin color, 62% are married or have a stable union, and 69.3 % belong to class C. Of the elderly, 66.4% have a minimum level of education up to full elementary education II. The mean age of the studied group was 71 years (standard deviation = 0.6), about 47% of them, almost half, were less than 70 years old (Table 2).

Table 2: Distribution of sociodemographic characteristics of the elderly-NAI, Hospital das Clínicas, Recife, 2015-2016.

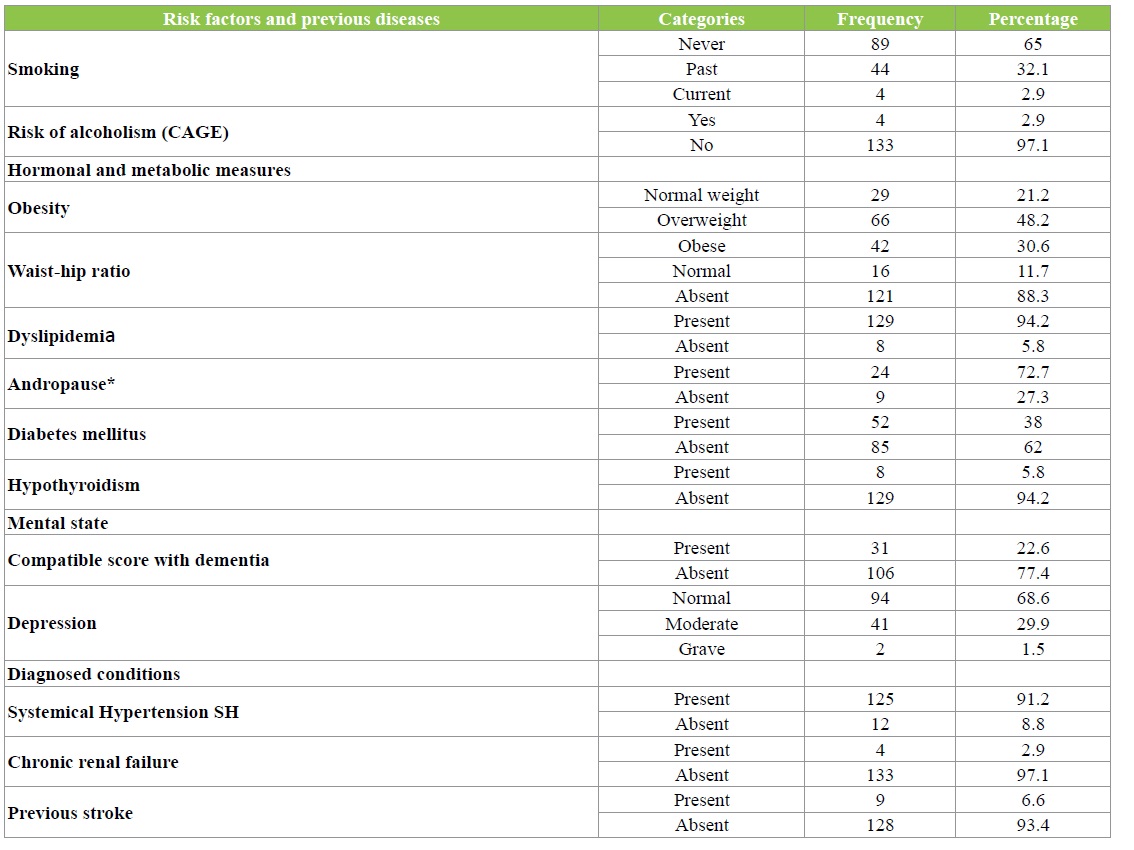

Analyzing the clinical variables of the present study, 78.8% of the elderly were overweight or obese, 72.3% had a waist/hip circumference index higher than normal and 94, 2% have dyslipidemia (Table 3).

Table 3: Frequency distribution of risk factors for cardiovascular disease and previous diseases of the elderly - NAI, Hospital das Clinicas, Recife, 2015-2016.

Regarding the assessment of mental state, in the cognitive evaluation, 22.6% of the elderly had a mini-mental test compatible with dementia, and 31.4% had a moderate or severe depression. In the cardiovascular evaluation, practically the majority have hypertension (91.2%), 35% with CAD defined or possible and 27.7% with cardiac arrhythmia, and the same percentage has LVH (Table 3).

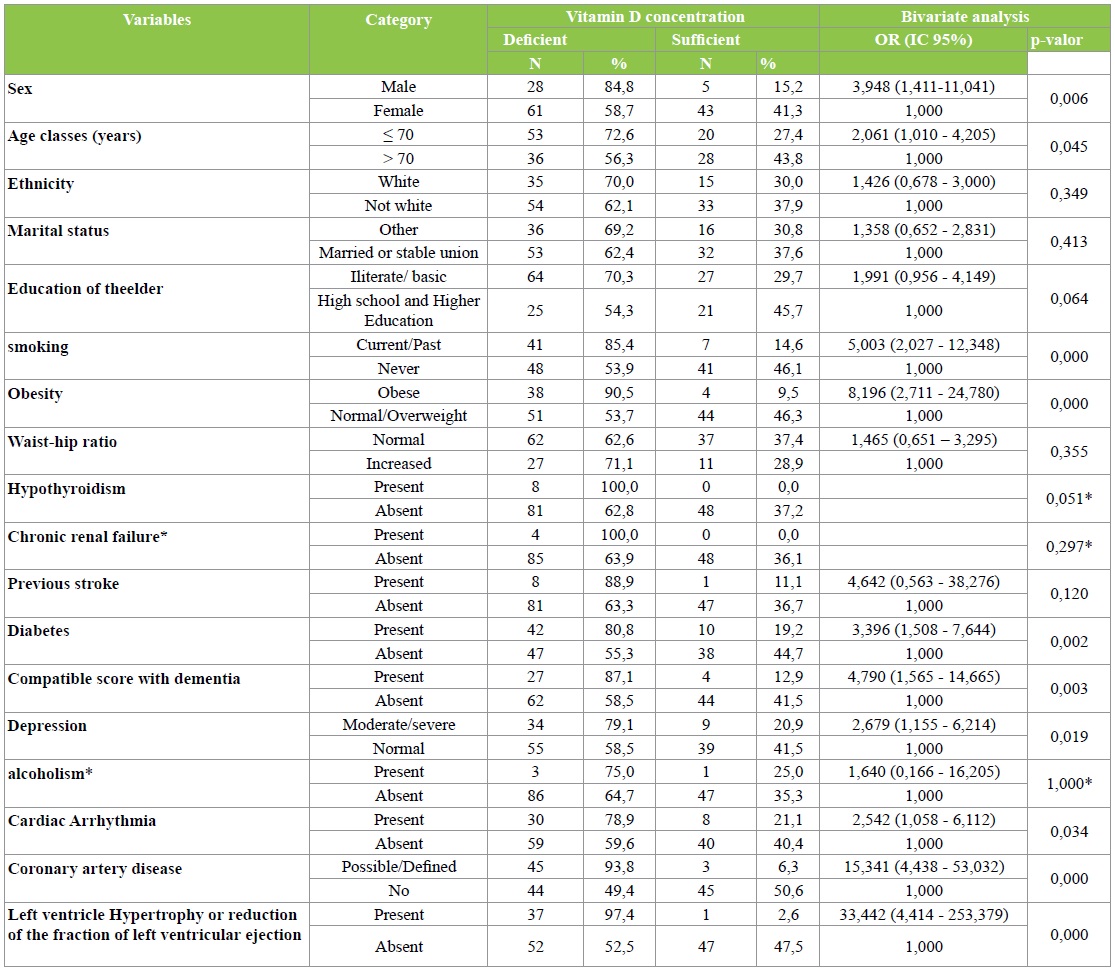

In order to verify the existence of association of the vitamin D concentration with the variables related to the socio-demographic characteristics of the elderly and the other clinical variables, Fisher’s exact test was applied and presented in Table 4 the results in which this association was significant. The elderly groups with the highest odds of presenting vitamin D deficiency were male, 70 years of age or older, smoking, obese, diabetic, with dementia score, with depression, cardiac arrhythmia, CAD and with LVH or Reduction of left ventricular ejection fraction.

Table 4: Association of sociodemographic and clinical variables with the concentration of Vitamin D – NAI, Hospital das Clínicas, Recife – 2016.

Discussion

The majority of the elderly in this study were overweight or obese, as well as having a waist index above normal, a high prevalence of dyslipidemia and systemic arterial hypertension, according to the literature, where aging is associated with a higher prevalence of alterations in glycemic metabolism, central obesity, dyslipidemia and hypertension, characterizing Metabolic Syndrome [16].

Although vitamin D deficiency is well documented in elderly people living in countries of the northern hemisphere, in Brazil there is evidence of a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency, as in a temperate climate study in São Paulo that demonstrated hypovitaminosis D in 43.5% of the active elderly, 87.6% of the elderly living in communities and 91.5% of those institutionalized [17]. In the present study conducted in Recife, northeast of the country, where the tropical climate predominates most of the time, we found a high percentage (65%) of vitamin D deficiency similar to NHANES III data [18].

The prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in the present study was also lower than that reported in the French population, mainly above 60 years (80.3%) [19], as well as in northern India, near the Himalaya, where the prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was 83%, associated with chronic stable angina considering the greater latitude of these countries [20], where the winters are longer and the individuals use clothes that cover practically the whole body, in contrast to the regions near the line of the Equator, Where sunny weather predominates most of the year.

Although there is no uniformity in the literature regarding cut-off points and dosage method, vitamin D deficiency is considered by the Institute of Medicine at a concentration of 25-hydroxyvitamin D less than 20 ng/mL and insufficiency when there are levels between 21 and 29 ng/ml [21].

However, this nomenclature changes. Thus, most studies consider deficient 25 (OH) D levels below 30 ng/mL, such as the Endocrine Society, the National Osteoporosis Foundation (NOF), the International Osteoporosis Foundation (IOF), and the American Geriatric Society (AGS). Severe deficiency when less than 20 ng/mL, but also the studies with results expressed in nmol/L classified the severe deficiency in the presence of levels below 25 nmol/L, moderate of 25 to 49.9 nmol/L, insufficiency of 51 At 75 nmol/L [21,22]. In this present study, the presence of 25 (OH) D levels below 30ng/ mL was considered as vitamin D deficiency.

As a justification for the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly, as related in this research, the literature exposes several factors, such as obesity, chronic liver or kidney diseases, diseases that impair fat absorption, lifestyle and environmental factors, such as institutionalization, reduction of outdoor physical activity, functional limitation [23], leading to less sun exposure and less outdoor activities, type of clothing, inadequate diet, use of medications that may interfere with vitamin D metabolism and, especially, reduced intake epidermal production of the vitamin D precursor due to skin atrophy due to aging [11].

The analysis of the previous clinical characteristics of the elderly sample of the present study underscores the importance of this approach, since about 30% of this elderly had a history of cardiac arrhythmia, Left ventricular hypertrophy (LVH) and CAD. In this study, a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was found in men, and it can be justified considering that women use vitamin D supplementation, because they are more affected than men by osteoporosis, as well as frequent health service are more subject to preventive medicine than men [24].

One of the limitations of this study did not quantify the elderly who were already using supplementation with vitamin D and it is worth mentioning that old women accompanied the services of this study are also accompanied by gynecologists and geriatricians, which are usually evaluated in a preventive or therapeutic as osteoporosis.

The clinical conditions presented by the elderly in this study, such as smoking, obesity, DM II, scores compatible with dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia, CAD, and LVH were related to a higher prevalence of vitamin D deficiency. The association between smoking and vitamin D deficiency, found in this study, may be related to inflammatory mechanisms present in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) [25], as well as the functional limitations and greater sedentary lifestyle that these patients with COPD present, with less time of sun exposure, as well as by accelerated skin aging due to smoking, renal dysfunction and use of corticosteroids in COPD [26].

The association between obesity and vitamin D deficiency found in this study was also demonstrated in in another study, when 10.331 participants were cross-checked, finding an inverse association between waist circumference and calcidiol levels and systolic blood pressure [27]. It is worth mentioning that obese elderly people, due to their greater difficulty in locomotion, are less exposed to the sun, have less vitamin D3 hepatic synthesis and are more absorbed by body fat deposits and thus have lower serum levels of 25 hydroxyvitamin D [28].

Regarding the association between vitamin D deficiency and diabetes in the present study, this was widely evaluated by several authors [29-32] as well as showing that the risk of DM II can be reduced by 41% if levels of 25 (OH) D are sufficient [33].

The finding of the association between vitamin D deficiency and cognitive decline, assessed by the Mental State Minisex of this study was similar to that reported by Llewellyn et al. [34-37] with vitamin D being considered an essential neurohormonal hormone in the function of brain regulation and protection, against cognitive decline and Alzheimer’s disease [38].

Depression is considered a cardiovascular risk factor, increased twice the risk of AMI and up to 2.5 years of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality [39] was correlated in this vitamin D-deficient research, being in concordance with works in the literature that found association between levels of vitamin D and depression [40-43]. A scientific research demonstrated the actions of this vitamin in the central nervous system, as well as the meta-analysis demonstrated a positive association between depression and vitamin D deficiency, indicates that vitamin supplementation may promote a significant improvement of this disorder and more recently, as demonstrated in a recent study conducted in teachers in Malaysia, where there was a high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency with low levels of this vitamin significantly associated with depression and worse quality of life [44-46].

The association between hypovitaminosis D and cardiac arrhythmia, mainly atrial fibrillation(AF) whose data were confirmed in the present study were also described by [6,47- 50], and several mechanisms to explain this association are described, such as the negative regulation of calcitriol over Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System (RAAS), reducing the oxidative stress, decreasing reactive oxygen species and inflammation [51], and prolonging the action potential through its role in the regulation of calcium metabolism [52]. However, other studies [53-55], based on the prospective cohort of the Rotterdam Study, evaluated the elderly with a 12-year follow-up, also did not find this association.

Although significant advances in primary prevention and treatment strategies for CAD, especially in the geriatric population, which are exposed to higher risks of worse outcomes after acute coronary syndrome, this remains the leading cause of death in developed countries [56].

In a recent study, evaluated octogenarians undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention, found that they had a 10.6 times higher risk of mortality after AMI with ST segment elevation, as well as acute stent thrombosis, previous AMI, Cardiac insufficiency, low left ventricular ejection fraction, ventricular arrhythmias and multiarterial lesions are the independent risk factors for in-hospital mortality in this population [57]. As explanation for these worse results of CAD in the elderly could be due to poor nutrition and low levels of vitamin D in this population favoring the pathogenesis of these complications [56].

The CAD in association with the vitamin D deficiency found in this study was related in many studies, such as the large prospective study of HPFS [3] and others such as the Framingham Offspring Prospective Study [58], Cardiovascular Health Study [59], Augsburg Case-Cohort Study [5], which revealed an inverse association between vitamin D levels and CAD. The interpretation for the association between CAD and vitamin D deficiency may be due to possible inflammatory mechanism induced by Vitamin D deficiency leads to oxidative stress and release of proinflammatory cytokines causing platelet activation and release by the bone marrow of immature platelets with increased volume and activated with a higher rate of collagen aggregation, high levels of thromboxane A2, favoring greater expression of glycoproteins Ib and IIb/IIIa, leading to an increased risk of CAD [60].

It was observed that evaluating epicardial coronary flow in 222 patients submitted to coronary angiography due to suspicion of ischemic heart disease, thickening of the intima and averages carotid ultrasound as a marker of subclinical atherosclerosis and dilation of the brachial artery mediated flow as an indicator of endothelial dysfunction, found strong association between vitamin D insufficiency and coronary slow flow as well as endothelial dysfunction and subclinical atherosclerosis were more prevalent among subjects with vitamin D insufficiency [7].

As to the percentage of elderly patients with poor left ventricular systolic function or LVH associated with vitamin D deficiency, in the present study, this correlation with literature data was demonstrated [61], as well as related to pathophysiological mechanisms by which vitamin D acts in LVH through of VDR receptor, inhibiting RAAS [62,63]. Calcitriol, through its VDR receptor regulates the proliferation, morphology and growth of cardiomyocytes, and reduces the expression of the Atrial Natriuretic Factor and increases the expression and nuclear localization of the VDR in these cells [64,65].

Vitamin D exerts its anti-inflammatory role in LVH, reducing IL-2, TNF alpha, interferon gamma, TH1 lymphocytes [66] and reducing the expression of TNFalpha and NF-kapa beta messenger RNA (In the present study, it was found that the TIMPs were able to inhibit the degradation of the extracellular matrix, which could prevent the evolution to HF [67]. VDR receptor type BSMI, which were related to LVH [68].

Was performed a cross-sectional study in elderly patients attending cardiology outpatient clinics of the UFPE, in Recife, from August 2015 to February 2016, in order to analyze the association between vitamin D deficiency and heart failure risk. Using bivariate logistic analysis, followed by multivariate logistic regression analysis, the authors found that among 137 elderly, the risk of heart failure was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency, male gender, obesity and cardiac arrhythmia. The increased risk of heart failure in this study was present in more than half of the elderly and was significantly associated with vitamin D deficiency (growing 12.2 times the risk of heart failure) [69].

Cardiovascular diseases in the elderly have been considered a challenge for public health, being causes of high mortality in this population, despite the greater disclosure of healthy aging, even in developed countries. Hence the importance of developing research to identify possible causes of cardiovascular risk, which could be directed to public health policies and actions and among such research, vitamin D deficiency.

The reduction of calcitriol leads to an increase in the production of PTH, extracellular matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs), Tumor Necrosis Factor alpha (TNF alpha), Advanced glycation end products (AGEs), reduction of carboxyglutamic acid matrix protein ( matrix GLA protein) which is a dependent vitamin K, associated with the reduction of arterial calcification, reduction of osteopontin, of Interleukin-10 and type IV collagen, changes that lead to the formation of arterial calcification which in turn increases the risk of DCV [70]. The other mechanism of increased CVD-induced vitamin D deficiency is the increase in ANP (Natriuretic Atrial Peptide), changes in cardiomyocyte contractility, and decreased synthesis of extracellular matrix inhibitors (TIMPs), causing LVH and therefore heart failure and death [71,72].

Searched in the literature for evidence of a causal association between low vitamin D levels and increased risk of cardiovascular disease, based on Hill criteria and found that all relevant Hill criteria for a causal association in a biological system have been met, to indicate that vitamin deficiency is a risk factor for cardiovascular disease [72].

The strength of this study was the reduced loss of data due to the lack of records in the medical records, as well as the use of a wide range of complementary tests, investigating several aspects of the health conditions of the elderly, as well as making it possible to evaluate the cardiological aging to guide the conduct therapy.

All patients in this study underwent Doppler echocardiography and the findings of left ventricular hypertrophy and reduction of LV function analised by this method, were associated with vitamin D deficiency, demonstrating the importance of this test, due to alterations in the structure and cardiac function in the elderly are usually subclinical, which often precede the development of heart failure.

Based on the evidence presented in the present study, supported by the literature, it can be stated that the high percentage of elderly people with vitamin D deficiency and their association with cardiovascular risk factors suggests that vitamin D recommendations should be implemented especially in services of basic health care. The ease of quantification of vitamin D, the low cost of its supplementation and the possibility of preventing and treating cardiovascular diseases seem to point to the need for a greater amount of studies of vitamin D supplementation in a prospective cohort, so that the supplementation conduct is implanted with a solid evidence base.

Among the limitations of this study is the transversal nature, which makes it impossible to establish causal relationships, as well as the fact that it was performed through medical records analyzes, since it did not contain more detailed information such as physical exercise practice, quantification of patients who used of vitamin D supplementation. However, this limitation was reduced because the data collection was done in specialized places to care for the elderly, maintaining a broad and systematized research routine, with better cardiovascular risk assessment conditions. It was also not possible to identify bone densitometry, serum calcium, phosphorus and PTH dosages in all patient charts of this study, and the presence of osteoporosis in the elderly could not be quantified, and well better analysis of bone metabolism.

Another limitation of the present study was the no quantification of LV diastolic dysfunction in the elderly, since it is a very frequent alteration in this age range [73,74].

Conclusions

A high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency was detected in this population of elderly people. These results were significantly associated in this study with males and the age range ≤ 70 years, in the same way associated with cardiovascular risk factors such as smoking, obesity, DMII, dementia, depression, cardiac arrhythmia and, mainly, a strong association with CAD and hypertrophy or reduction of left ventricular function.

Observational data support the relationship between vitamin D levels and cardiovascular disease and therefore vitamin D deficiency can be considered a marker of cardiovascular risk. Large randomized controlled trials are needed to establish protocols to establish which optimal levels of 25-Hydroxyvitamin D are recommended to maintain a healthy profile in patients with CVD. This maintenance of an ideal serum vitamin D level is of fundamental importance, not only for regulation of calcium balance, but also to decrease cardiovascular risk, to control systemic arterial pressure, inhibiting the progression of atherosclerosis and consequently preventing CAD and peripheral arterial disease, as a neuroprotective agent in the prevention of stroke, dementia and depression and controlling the constituent elements of the metabolic syndrome.

The evidence presented in this study, supported by the literature, may be relevant for primary health care, considering the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in the elderly population, as well as being a treatable condition with low cost supplementation. Vitamin D supplementation may be combined with antihypertensives or antidiabetics as a simple prophylactic agent for cardiovascular morbidities, especially in the elderly, where small gains in prevention are important from a public health point of view.

These actions can be very important in guiding public health policies, considering the high prevalence of vitamin D deficiency and aging of the population. The benefits of this public health approach to vitamin D assessment and treatment may probably reflect a reduction in cardiovascular morbidity and mortality.

Declaration of Interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for writing the paper and the contents therein.

Gravina CF, Franken R, Wenger N, Freitas EV, Batlouni M, et al. (2010) II diretrizes em cardiogeriatria da Sociedade Brasileira de Cardiologia. Arq Bras Cardiol 95: e16-e76. [ Ref ]

Sociedade Brasileira de Nefrologia (2010) VI Brazilian Guidelines on Hypertension. Arq Bras Cardiol 95: 1-51. [ Ref ]

Giovannucci E, Liu Y, Hollis BW, Rimm EB (2008) 25-hydroxyvitamin D and risk of myocardial infarction in men: a prospective study. Arch Intern Med 168: 1174-1180. [ Ref ]

Anderson JL, May HT, Horne BD, Bair TL, Hall NL, et al. (2010) Relation of vitamin D deficiency to cardiovascular risk factors, disease status, and incident events in a general healthcare population. Am J Cardiol 106: 963-968. [ Ref ]

Karakas M, Thorand B, Zierer A, Huth C, Meisinger C, et al. (2013) Low levels of serum 25-Hydroxyvitamin D are associated with increased risk of myocardial infarction, especially in women: results from the MONICA/ KORA Augsburg case-cohort study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 272-280. [ Ref ]

Tomson J, Emberson J, Hill M, Gordon A, Armitage J, et al. (2013) Vitamin D and risk of death from vascular and non-vascular causes in the whitehall study and meta-analyses of 12.000 death. Eur Heart J 34: 1365-1374. [ Ref ]

Oz F, Cizgici AY, Oflaz H, Elitok A, Karaayvaz EB, et al. (2013) Impact of vitamin D insufficiency on the epicardial coronary flow velocity and endothelial function. Coron Artery Dis 24: 392-397. [ Ref ]

Ginde AA, Scragg R, Schwartz RS, Camargo CA Jr (2009) Prospective study ofserum25-hydroxyvitaminD level, cardiovascular disease mortality, and all-cause mortality in older U.S. adults. J Am Geriatr Soc 57: 1595-1603. [ Ref ]

Perna L, Schöttker B, Holleczek B, Brenner H (2013) Serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D and incidence of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events: a prospective study with repeated measurements. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 98: 4908-4915. [ Ref ]

Theodoratou E, Tzoulaki I, Zgaga L, Ioannidis JP (2014) Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: umbrella review of systematic reviews and meta-analyses of observational studies and randomised trials. BMJ 348: g2035. [ Ref ]

Hossein-Nezhad A, Michael F, Holick MF (2013) Vitamin D for Health: a global perspective. Mayo Clin Proc 88: 720-755. [ Ref ]

Henry HL, Bouillon R, Norman AW, Gallagher JC, Lips P, et al. (2010) 14th Vitamin D Workshop consensus on vitamin D nutritional guidelines. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 121: 4-6. [ Ref ]

Khaw KT, Luben R, Wareham N (2014) Serun 25-hydroxyvitamin D, mortality, and incidente cardiovascular disease, respiratory disease, cancers, and fractures; a 13-y prospective populations study. Am J Clin Nutr 100: 1361-7130. [ Ref ]

Pareja-Galeano H, Alis R, Sanchis-Gomar F, Lucia A, Emanuele E (2015) Vitamin D, precocious acute myocardial infarction, and exceptional longevity. Int J Cardiol 199: 405-406. [ Ref ]

Franco I (1994) It deals with the national policy of the elderly, creates the National Council for the Elderly and provides other measures, [http:// www.planalto.gov.br/ccivil_03/leis/L8842.htm]. 20 September 2016. [ Ref ]

Hildrum B, Mykletun A, Hole T, Midthjell K, Dahl AA (2007) Age-specific prevalence of the metabolic syndrome defined by the International Diabetes Federation and the National Cholesterol Education Program: the Norwegian HUNT 2 study. BMC Public Health 7: 220. [ Ref ]

Maeda SS, Saraiva GL, Kunni IS, Hayashi LF, Cendoroglo MS, et al. (2013) Factors affecting vitamin D status in different populations in the city of São Paulo, Brazil: the São Paulo vitamin D valuation Study (SPADES). BMC Endocr Disord 13: 14. [ Ref ]

Martins D, Wolf M, Pan D, Zadshir A, Tareen N, et al. (2007) Prevalence of cardiovascular risk factors and the serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D in the United States: data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Arch Int Med 67: 1159-1165. [ Ref ]

Souberbielle JC, Massart C, Brailly-Tabard S, Cavalier E, Chanson P (2016) Prevalence and determinants of vitamin D deficiency in healthy French adults: the VARIETE study. Endocrine 53: 543-550. [ Ref ]

Raina AH, Allai MS, Shah ZA, Changal KH, Raina MA, et al. (2016) Association of low levels of vitamin D with chronic stable angina: a prospective case-control study. N Am J Med Sci 8: 143-150. [ Ref ]

Holick MF, Binkley NC, Bischoff-Ferrari HA, Gordon CM, Hanley DA, et al. (2011) Evaluation, treatment, and prevention of vitamin D deficiency: an endocrine society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocr Metabol 96: 1911-1930. [ Ref ]

American Geriatrics Society Consensus Statement (2014) Vitamin D for prevention of falls and their consequences in older Adults year of publication. American Geriatrics Society. [ Ref ]

Lavie CJ, Lee JH, Milani RV (2011) Vitamin D and cardiovascular disease will it live up to its hype? J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 1547-1556. [ Ref ]

Chaimowicz F and Camargos MCS (2011) Envelhecimento e saúde no Brasil. In: Freitas EV, Py L, editores. Tratado de geriatria e gerontologia. 3. ed. Rio de Janeiro: Guanabara Koogan, 74-98. [ Ref ]

Penna G and Adorini L (2000) 1α,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 Inhibits Differentiation, Maturation, Activation, and Survival of Dendritic Cells Leading to Impaired Alloreactive T Cell Activation. J Immunol 164: 2405-2411. [ Ref ]

Holick MF (2007) Vitamin D deficiency. N Engl J Med 357 :266-281. [ Ref ]

Vogt S, Baumert J, Peters A, Thorand B, Scragg R (2016) Waist circumference modifies the association between serum 25(OH)D and systolic blood pressure: results from NHANES 2001-2006. J Hypertens 34: 637-645. [ Ref ]

Wortsman J, Matsuoka LY, Chen TC, Lu Z, Holick MF (2000) Decreased bioavailability of vitamin D in obesity. Am J Clin Nutr 72: 690-693. [ Ref ]

Pittas AG, Harris SS, Stark PC, Dawson-Hughes B (2007) The effects of calcium and vitamin D supplementation on blood glucose and markers of inflammation in nondiabetic adults. Diabetes Care 30: 980-986. [ Ref ]

Gradinaru D, Borsa C, Ionescu C, Margina D, Prada GI, et al. (2012) Vitamin D status and oxidative stress markers in the elderly with impaired fasting glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus. Aging Clin Exp Res 24: 595-602. [ Ref ]

Kuloğlu O, Gür M, Şeker T, Kalkan GY, Kırım S, et al. (2013) Serum hydroxyvitamin D level is associated with aortic distensibility and left ventricle hypertrophy in newly diagnosed type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diab Vasc Dis Res 10: 546-549. [ Ref ]

Raska I Jr, Rašková M, Zikán V, Škrha J (2016) High prevalence of hypovitaminosis D in postmenopausal women with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Prague Med Rep 117: 5-17. [ Ref ]

Forouhi NG, Ye Z, Rickard AP, Khaw KT, Luben Ret al. (2012) Circulating 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration and the risk of type 2 diabetes: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer (EPIC)- Norfolk cohort and updated meta-analysis of prospect,ive studies. Diabetologia 55: 2173-2182. [ Ref ]

Llewellyn DJ, Lang IA, Langa KM, Melzer D (2011) Vitamin D and cognitive impairment in the elderly US population. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 66: 59-65. [ Ref ]

Przybelski RJ and Binkley NC (2007) Is vitamin D important for preserving cognition? A positive correlation of serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D concentration with cognitive function. Arch Biochem Biophys 460: 202-205. [ Ref ]

Annweiler C, Fantino B, Schott AM, Krolak-Salmon P, Allali G, et al. (2012) Vitamin D insufficiency and mild cognitive impairment: crosssectional association. Eur J Neurol 19: 1023-1029. [ Ref ]

Balion C, Griffith LE, Strifler L, Henderson M, Patterson C, et al. (2012) Vitamin D, cognition, and dementia: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Neurology 79: 1397-1405. [ Ref ]

Keeny JT and Butterfield DA (2015) Vitamin D deficiency and Alzheimer disease: common links. Neurobiol Dis 84: 84-98. [ Ref ]

Lett HS, Blumenthal JA, Babyak MA, Sherwood A, Strauman T, et al. (2004) Depression as a risk factor for coronary artery disease: evidence, mechanism, and treatment. Psychosom Med 66: 305-315. [ Ref ]

Wilkins CH, Sheline YI, Roe CM, Birge SJ, Morris JC (2006) Vitamin D deficiency is associated with low mood and worse cognitive performance in older adults. Am J Psychiatry Geriatr 14: 1032-1040. [ Ref ]

Armstrong DJ, Meenagh GK, Bickle I, Lee AS, Curran ES, et al. (2007) Vitamin D deficiency is associated with anxiety and depression in fibromyalgia. Clin Reumatol, 26: 551-554. [ Ref ]

Jorde R, Waterloo K, Saleh F, Haug E, Svartberg J (2006) Neuropsychological function in relation to serum parathyroid hormone and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. J. Neurol 253: 464-470. [ Ref ]

Hoogendijk WJ, Lips P, Dik MG, Deeg DJ, Beekman AT, et al. (2008) Depression is associated with decreased 25-hydroxyvitamin D and increased parathyroid hormone levels in older adults. Arch Gen Psychiatry 65: 508-512. [ Ref ]

Yeshokumar AK, Saylor D, Kornberg MD, Mowry EM (2015) Evidence for the importance of vitamin D status in neurologic conditions. Curr Treat Options Neurol 17: 51. [ Ref ]

Spedding S (2014) Vitamin D and depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis comparing studies with and without biological flaws. Nutrients 6: 1501-1518. [ Ref ]

Moy FM, Hoe VC, Hairi NN, Vethakkan SR, Bulgiba A (2017) Vitamin D deficiency and depression among women from an urban community in a tropical country. Public Health Nutr 20: 1844-1850. [ Ref ]

Frost L, Søren, PJ, Pedersen L, Husted S, Engholm G, et al. (2002) Seasonal variation in hospital discharge diagnosis in atrila fibrillation: a population-based study. Epidemiology 13: 211-215. [ Ref ]

Murphy NF, Stewart S, MacIntyre K, Capewell S, McMurray JJ (2004) Seasonal variation in morbiditie and mortality related to atrial fibrillation. Int J Cardiol 97: 283-288. [ Ref ]

Demir M, Uyan U, Melek M (2014) The effects of vitamin D deficiency on atrial fibrillation. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 20: 98-103. [ Ref ]

Chen WR, Liu ZY, Shi Y, Yin DW, Wang H, et al. (2014) Relation of low vitamin D to nonvalvular persistent atrial fibrillation in chinese patients. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 19: 166-173. [ Ref ]

Lappegard KT, Hovland A, Pop GA, Mollnes TE (2013) Atrial fibrillation: inflammation in disguise? Scand J Immunol 78: 112-119. [ Ref ]

Hafany DA, Chang S, Lu Y, Chen Y, Kao Y, et al. (2014) Electromechanical effects of 1,25-dihydrixyvitaminaD with antiatrial fibrillation activities. J Cardiovasc Electrophysiol 25: 317-323. [ Ref ]

Rienstra M, Cheng S, Larson MG, McCabe EL, Booth SL, et al. (2011) Vitamin D status is not related to development of atrial fibrillation in the community. Am Heart J 62: 538-541. [ Ref ]

Qayyum F, Landex NL, Agner BR, Rasmussen M, Jøns C, et al. (2012) Vitamin D deficiency is unrelated to type of atrial fibrillation and its complications. Dan Med J 59: A4505. [ Ref ]

Vitezova A, Cartolano NS, Heeringa J, Zillikens MC, Hofman A, et al. (2015) Vitamin D status and atrial fibrillation in the elderly: the rotterdam study. PLoSOne 10: e0125161. [ Ref ]

Kunadian V, Ford GA, Bawamia B, Qiu W, Manson JE (2014) Vitamin D deficiency and coronary artery disease: a review of the evidence. Am Heart J 167: 283-291. [ Ref ]

Ipek G, Kurmus O, Koseoglu C, Onuk T, Gungor B, et al. (2017) Predictors of in-hospital mortality in octogenarian patients who underwent primary percutaneous coronary intervention after ST segment elevated myocardial infarction. Geriatr Gerontol Int 17: 584-590. [ Ref ]

Wang TJ, Pencina MJ, Booth SL, Jacques PF, Ingelsson E, et al. (2008) Vitamin D deficiency and risk of cardiovascular disease. Circulation 117: 503-511. [ Ref ]

Kestenbaum B, Katz R, de Boer I, Hoofnagle A, Sarnak MJ, et al. (2011) Vitamin D, parathyroid hormone, and cardiovascular events among older adults. J Am Coll Cardiol 58: 433-441. [ Ref ]

Cure MC, Cure E, Yuce S, Yazici T, Karakoyun I, et al. (2014) Mean platelet volume and vitamin D level. Ann Lab Med 34: 98-103. [ Ref ]

Fall T, Shiue I, Bergeå af Geijerstam P, Sundström J, Ärnlöv J, et al. (2012) Relations of circulating vitamin D concentrations with left ventricular geometry and function. Eur J Heart Fail 14: 985-991. [ Ref ]

Li YC (2003) Vitamin D regulation of the renin-angiotensin system. J Cell Biochem 88: 327-331. [ Ref ]

Xiang W, Kong J, Chen S, Cao LP, Qiao G, et al. (2005) Cardiac hypertrophy in vitamin D receptor knockout mice: role of the systemic and cardiac renin-angiotensin systems. Am J Physio Endocrino Metab 288: E125-E132. [ Ref ]

Mancuso P, Rahman A, Hershey SD, Dandu L, Nibbelink KA, et al. (2008) 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 treatament reduces cardiac hypertrophy and left ventricular diameter in spontaneously hypertensive heart failure prone(cp/+) rats independent of changes in serum leptin. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 51: 559-564. [ Ref ]

Zittermann A and Koefer R (2008) Vitamin D in the prevention and treatment of coronary heart disease. Curr Pin Clin Nutr Metab Care 11: 752-757. [ Ref ]

Helming L, Böse J, Ehrchen J, Schiebe S, Frahm T, et al. (2005) 1alpha,25- dihydroxyvitamin D3 is a potent suppressor of interferon gammamediated macrophage activation. Blood 106:4351-4358. [ Ref ]

Rahman A, Hershey S, Ahmed S, Nibbelink K, Simpson RU (2007) Heart extracellular matrix gene expression profile in the vitamin D receptor knockout mice. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 103: 416-419. [ Ref ]

Santoro D, Gagliostro G, Alibrandi A, Ientile R, Bellinghieri G, et al. (2014) Vitamin D receptor gene polymorphism and left ventricular hypertrophy in chronic kidney disease. Nutrients 10: 1029-1037. [ Ref ]

Porto CM, Silva VDL, da Luz JSB, Filho BM, da Silveira VM (2017) Association between vitamin D deficiency and heart failure risk in the elderly. ESC Heart Fail 5: 63-74. [ Ref ]

Liu M, Li X, Sun R, Zeng YI, Chen S, et al. (2016) Vitamin D nutritional status and the risk for cardiovascular disease. Exp Ther Med 11: 1189- 1193. [ Ref ]

Polyakova V, Loeffler I, Hein S, Miyagawa S, Piotrowska I, et al. (2011) Fibrosis in endstage human heart failure: severe changes in collagens metabolism and MMP/TIMP profiles. Int J Cardiol 151: 18-33. [ Ref ]

Weyland PG, Grant WB, Howie-Esquivel J (2014) Does sufficient evidence exist to support a causal association between vitamin D status and cardiovascular disease risk? An Assessment Using Hill’s Criteria for CausalityNutrients 6: 3403-3430. [ Ref ]

Moutinho MAE, Colucci FA, Alcoforado V, Tavares LR, Rachid MBF, et al. (2008) Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction and systolic dysfunction in the community. Arq Bras Cardiol 90: 132-137. [ Ref ]

Goldraich L, Clausell N, Biolo A, Beck-da-Silva L, Rohde LE, et al. (2010) Preditores clínicos de fração de ejeção de ventrículo esquerdo preservada na insuficiência cardíaca descompensada. Arq Bras Cardiol 94: 364-371. [ Ref ]