Journal Name: Journal of Health Science and Development

Article Type: Research

Received date: 07 April, 2023

Accepted date: 16 May, 2023

Published date: 2024-02-01

Citation: Albagdady M, Alotaibi H, Sadek AA, Alali A, Hands J et al. (2023) Clinical Attire Preference among Patients in Military Healthcare Facilities in Kuwait. J Health Sci Dev Vol: 6, Issue: 1 (01-07).

Copyright: © 2023 Albagdady M et al. This is an openaccess article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Objectives: Military healthcare professionals often consult patients while wearing their full military uniforms, which may affect patients’ clinical experience. This study aims to understand patients’ opinion concerning clinicians’ attire with regard to patients’ preference, ease in declaring personal or private information, comfort in asking for further information or raising concerns, and confidence in maintaining privacy and confidentiality in a military setting.

Methods: Patients attending outpatient clinics in two military medical facilities in Kuwait were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their preference for clinician attire and any effect on their comfort or confidence in the clinicians. The study took place in 2021.

Results: The overall response rate was 94.6% (n=937). Most participants were neutral regarding all statements. However, female participants preferred their doctors to be in military uniforms in comparison with males (P=0.000). Non-Kuwaiti participants felt more comfortable sharing private/personal information and asking for clarification or raising concerns with a doctor in military uniform (p=0.007). Civilian participants also preferred doctors in military uniform (p=0.000). Officers preferred their doctor to be in military uniform (p=0.014), whereas non-commissioned officers preferred their doctor to be in civilian attire (p=0.000).

Conclusion: Patients visiting military medical facilities do not prefer a certain attire, and attire does not influence their perception of the physicians’ competence. This may lead us to conclude that doctors’ attire, regardless of being civilian or military, may not be the most concerning factor regarding the patient’s confidence and comfort and that the doctor-patient relationship is more vital. Therefore, further investigation of the psychological impact of doctor’s attire is highly recommended.

Keywords:

Military healthcare facilities, Clinical attire, Clinicians.

Abstract

Objectives: Military healthcare professionals often consult patients while wearing their full military uniforms, which may affect patients’ clinical experience. This study aims to understand patients’ opinion concerning clinicians’ attire with regard to patients’ preference, ease in declaring personal or private information, comfort in asking for further information or raising concerns, and confidence in maintaining privacy and confidentiality in a military setting.

Methods: Patients attending outpatient clinics in two military medical facilities in Kuwait were asked to complete a questionnaire regarding their preference for clinician attire and any effect on their comfort or confidence in the clinicians. The study took place in 2021.

Results: The overall response rate was 94.6% (n=937). Most participants were neutral regarding all statements. However, female participants preferred their doctors to be in military uniforms in comparison with males (P=0.000). Non-Kuwaiti participants felt more comfortable sharing private/personal information and asking for clarification or raising concerns with a doctor in military uniform (p=0.007). Civilian participants also preferred doctors in military uniform (p=0.000). Officers preferred their doctor to be in military uniform (p=0.014), whereas non-commissioned officers preferred their doctor to be in civilian attire (p=0.000).

Conclusion: Patients visiting military medical facilities do not prefer a certain attire, and attire does not influence their perception of the physicians’ competence. This may lead us to conclude that doctors’ attire, regardless of being civilian or military, may not be the most concerning factor regarding the patient’s confidence and comfort and that the doctor-patient relationship is more vital. Therefore, further investigation of the psychological impact of doctor’s attire is highly recommended.

Keywords:

Military healthcare facilities, Clinical attire, Clinicians.

Introduction

Studies showed that patient satisfaction is directly related to treatment adherence and thus higher rates of treatment success, with higher success rates occurring in medical facilities that have higher patient satisfaction and comfort [1-4]. The attire worn by medical staff has been shown to influence patient satisfaction significantly [5,6]. Thus, it is of great importance to ensure that medical staff wear the most appropriate attire. For civilian healthcare facilities, Petrilli et al5 showed that patients preferred formal attire with a white coat as most appropriate and stated that it affected their satisfaction with the care that they received.

The studies mentioned thus far examined civilian healthcare facilities. In contrast, military healthcare facilities consist of military and civilian healthcare professionals working alongside each other, and military personnel typically wear their full military uniforms. These facilities normally serve military personnel, their dependent families, and civilian employees of the establishment. Therefore, military healthcare professionals interact with both military and civilian patients.

Military-military interactions are typically dictated by a hierarchy structure, which may cause those of lower rank to be at unease when dealing with those of higher rank [7]. It is also possible that civilian patients could sometimes view military officers as a source of authority rather than merely healthcare providers. Both cases can result in misdiagnosis since patients may not disclose their full history or condition. For example, patients might not declare illegal drug use. To optimize treatment outcomes, patients’ comfort and satisfaction need to be increased. The correct choice of uniform could play a role in this, and therefore, hospitals should understand their patients’ preferences.

This study was performed to understand patients’ perceptions regarding military healthcare professionals’ attire in a clinical setting. The aim was to rate four aspects of patients’ experience when dealing with a healthcare professional in military uniform and when dealing with one in civilian attire. The four aspects are attire preference, ease in declaring personal or private information, comfort in asking for further information or raising concerns, and confidence in maintaining privacy and confidentiality. The results of this study could help create guidelines for military healthcare facilities in Kuwait to achieve higher patient satisfaction rates, which could improve the overall experience of service users.

Methods

Study population: Beneficiaries of the Medical Services Authority (MSA) of the Kuwaiti Ministry of Defense who attended outpatient department (OPD) clinics between the 21st of March and the 13th of April 2021 were invited to participate in this study. The study was performed at two MSA locations: Jabir Al Ahmad Armed Forces Hospital (a general hospital) and the Northern Medical Complex (a specialized clinical compound). 7626 and 2289 clinical visits occurred in these hospitals throughout the study period, respectively.

Patient and public involvement: Hospital patients volunteered to administer and evaluate the questionnaire in its early stages. They helped to word the questions and provided insight on the order in which the questions were presented. They suggested that paper format should be chosen to secure anonymity and decided that questionnaires must be handled by a team member to increase the response rate.

Sample size calculation: For calculating the sample size, the prevalence of a certain opinion of 50.0% was assumed to obtain the largest sample size, assuming a 95% confidence interval (CI) (Z=1.96), a 5% acceptable margin of error, a systematic sampling design effect coefficient of 1, and 2 groups for comparison. Calculations resulted in a sample size of 792 individuals, which was increased by 20% (990) to account for contingencies such as non-response and recording errors.

The following was used for sample size calculation:

where Z is the level of confidence measure and describes the level of uncertainty in the sample prevalence as an estimate of the population prevalence (recommended value: 1.96 for 95% confidence level). p is the baseline level of the indicator and the estimated prevalence of a certain opinion within the target population, and values closest to 50% are the most conservative (recommended value: 0.5 if there are there are no previous data on the population). e is the margin of error and the expected half-width of the confidence interval. The smaller the margin of error, the larger the sample size is needed (recommended value: 0.05).

The questionnaire: The questionnaire was developed after reviewing related studies and was then reviewed by a psychologist [7-10]. Two focus groups were held to ensure clarity of the questions. One consisted of healthcare professionals, and the other consisted of laymen. Furthermore, the questionnaire was administered to 56 volunteer hospital patients to evaluate its clarity before this study. Questions were adjusted accordingly.

The final questionnaire consisted of two parts. The first part was aimed at collecting demographic data (gender, nationality, age group, occupation, and educational level). Military personnel were also asked to note their rank. The second part was aimed at measuring patients’ opinions. A five-point Likert-scale questionnaire was created where patients were asked to rate their agreement with eight statements. Responses ranged from “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree.” The eight statements are shown in table 1. Paper format was chosen to ensure anonymity.

Data collection: Patients were approached by trained data collectors who were wearing civilian attire during their check-in procedure for their clinical appointments. Data collectors handed the questionnaire to those who agreed to participate, explained the study, and instructed patients to place the filled questionnaires in marked clear ballot boxes placed away from the view of data collectors and hospital staff. Copies of participant information sheets were available next to each box. The questionnaires were collected in the outpatient clinics of general and bariatric surgery, urology, plastic and burn surgery, orthopedics, ENT, ophthalmology, internal medicine, cardiology, neurology, psychiatry, dermatology, hyperbaric oxygen therapy, and dentistry. The response rate was considered as the percentage of filled-out questionnaires out of those handed out.

Exclusion criteria: Inpatients and casualty patients were excluded from this study due to the nature of these units, and only OPD patients were included. Questionnaires with unanswered biometric questions were included in the analysis. However, questionnaires with missing responses to statements were excluded from the analysis. In addition, for every comparison between responses to different demographic questions, data points for participants who did not answer specific questions were excluded from the particular analysis. For example, comparisons of responses across age groups did not include data from those who did not reveal their age.

Data analysis: Frequencies of responses for each questionnaire statement were calculated. A Mann-Whitney U-test was performed to assess differences in responses between males and females, Kuwaitis and non-Kuwaitis, Military and civilian participants, officers and noncommissioned officers, and patients of Jabir Al Ahmad Armed Forces Hospital and the Northern Complex. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare responses between different age groups and different educational levels. Data were analyzed using IBM SPSS data editor version 28.

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was granted by the Ministry of Defense Research Ethics Committee in October 2020 before starting the study. Participants’ information sheets were made available in both Arabic and English, and data collectors were also available for assistance. Agreement to participate was considered consent as questionnaires were anonymous. Participation was voluntary, and patients were assured that their decision would not affect their rights.

Results

The results showed a response rate of 94.6% among the respondents in this study (n =937). This high response rate was achieved due to the questionnaire distribution method. Table 2 shows the demographics of the respondents.

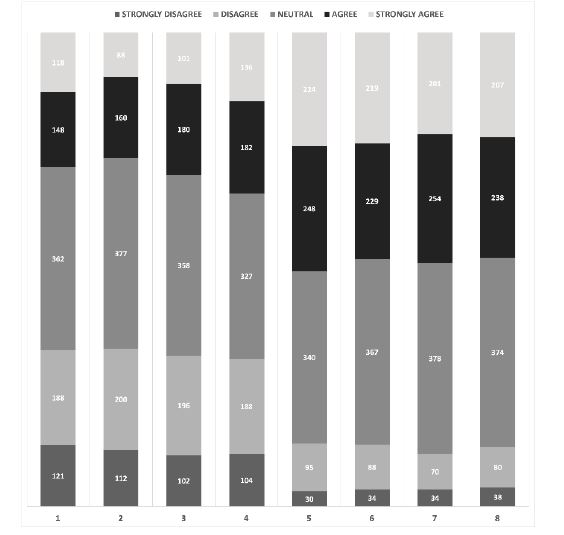

The overall questionnaire responses of the study population can be seen in figure 1 (n =937). The most selected response for each question was neutral. The figure shows that respondents favored dealing with a clinician in civilian attire. Several statistically significant differences were found between different sociodemographic variables, such as gender, nationality, sector, level of education, and military rank. Table 3 illustrates the differences in responses between male and female participants. More females preferred their doctors to be wearing military uniforms than males, while male patients preferred their doctor to be in civilian attire.

Table 1:Statements used in the questionnaire to measure patient’s responses.

| Question number | Statements |

|---|---|

| 1 | I prefer my doctor to be wearing his/her military uniform |

| 2 | I feel comfortable sharing private/personal information with a doctor in his/her military uniform |

| 3 | I feel comfortable asking for further information/explanation or raise concerns with a doctor wearing his/her military uniform |

| 4 | I feel that patient/doctor confidentiality is respected with a doctor wearing his/her military uniform |

| 5 | I prefer my doctor to be wearing civilian attire |

| 6 | I feel comfortable sharing private/personal information with a doctor in civilian attire |

| 7 | I feel comfortable asking for further information/explanation or raise concerns with a doctor wearing civilian attire |

| 8 | I feel that patient/doctor confidentiality is respected with a doctor wearing civilian attire |

Interestingly, in terms of nationality, it was found that non-Kuwaiti respondents felt more comfortable sharing private/personal information and asking for further explanation or raising concerns with doctors in military uniform when compared to Kuwaitis. Non-Kuwaiti patients felt more that doctor/patient confidentiality was more respected when dealing with a doctor in military uniform than Kuwaiti patients. Table 4 shows the different responses according to nationality.

Other interesting findings were the different responses of civilian and military participants (Table 5). Generally, civilians favored their doctors to be in military uniform, whereas military respondents preferred their doctors to be in civilian attire. The responses also varied according to the participant’s level of education. When compared to participants with higher degrees, patients that had high school diplomas or below felt more comfortable sharing personal information with doctors in civilian attire (p=0.025), felt comfortable asking for further explanation or raising concerns with doctors in civilian attire (p=0.001), and felt that patient/doctor confidentiality is more respected with doctors in civilian attire (p<0.001). No significant differences were found otherwise.

differences were found otherwise. Differences were also found in the preferences of officers and non-commissioned officers. The officers generally preferred their doctors to be in military uniform, while non-commissioned officers preferred their doctors to be in civilian attire. No significant differences (p<0.05) were found between the various age groups of participants. Additionally, there were no significant differences between participants from the Armed Forces Hospital and the Northern Medical Complex.

Discussion

One of the main reasons for studying healthcare providers’ attire is the importance of patients to be able to identify those providers [11-13]. Several studies have found that patients care about their physicians’ attire, whereas other studies showed that patients were satisfied with their doctors regardless of what they wore [12-16]. However, it was argued that patient perceptions of their physicians’ attire are influenced by various sociodemographic factors.5 In this study, the respondent’s gender, nationality, occupation, level of education, and military rank were the factors found to affect such perceptions.

Table 2:Characteristics of respondents.

| Characteristics | Respondents [n (%)] |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 645 (68.8) |

| Female | 292 (31.2) |

| Nationality | |

| Kuwaiti | 678 (72.4) |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 256 (27.3) |

| No response | 3 (0.3) |

| Age (years) | |

| 18 and below | 55 (5.9) |

| 19-29 | 213 (22.7) |

| 30-39 | 254 (27.1) |

| 40-49 | 197 (21) |

| 50-59 | 111 (11.8) |

| 60-69 | 73 (7.8) |

| 70 and above | 13 (1.4) |

| No response | 21 (2.2) |

| Sector | |

| Civilian | 496 (52.9) |

| Military | 440 (47) |

| No response | 1 (0.1) |

| Highest degree | |

| Highschool or below | 352 (37.6) |

| Diploma | 264 (28.2) |

| Bachelor’s degree | 263 (28.1) |

| Postgraduate degree | 55 (5.9) |

| No response | 3 (0.3) |

| Military rank | |

| Officers | 140 (38.6) |

| Non-commissioned officers | 223 (61.4) |

Table 3:Comparison of responses between male and female participants using Mann-Whitney U-test.

| Question | Gender | Mean Rank | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing his military uniform | Male | 436.85 | 0.000 |

| Female | 540.02 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private / personal information with a doctor in his military uniform | Male | 442.32 | 0.000 |

| Female | 527.93 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information / explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing his military uniform | Male | 443.07 | 0.000 |

| Female | 526.27 | ||

| I feel that patient / doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing his military uniform | Male | 441.97 | 0.000 |

| Female | 528.70 | ||

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing civilian attire | Male | 514.45 | 0.000 |

| Female | 368.61 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private/personal information with a doctor in a civilian attire | Male | 509.09 | 0.000 |

| Female | 380.45 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information/explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing civilian attire | Male | 502.33 | 0.000 |

| Female | 395.38 | ||

| I feel that patient/doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing civilian attire | Male | 507.49 | 0.000 |

| Female | 383.97 |

Table 4:Comparison of responses between Kuwaiti and non-Kuwaiti participants using Mann-Whitney U-test.

| Question | Nationality | Mean Rank | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing his military uniform | Kuwaiti | 457.29 | 0.05 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 494.55 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private / personal information with a doctor in his military uniform | Kuwaiti | 456.17 | 0.029 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 497.5 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information / explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing his military uniform | Kuwaiti | 453.44 | 0.007 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 504.73 | ||

| I feel that patient / doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing his military uniform | Kuwaiti | 447.75 | 0.000 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 519.81 | ||

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing civilian attire | Kuwaiti | 470.59 | 0.552 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 459.31 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private/personal information with a doctor in a civilian attire | Kuwaiti | 470.72 | 0.534 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 458.97 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information/explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing civilian attire | Kuwaiti | 470.32 | 0.584 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 460.03 | ||

| I feel that patient/doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing civilian attire | Kuwaiti | 470.74 | 0.530 |

| Non-Kuwaiti | 458.91 |

Table 5:Comparison of responses between civilian and military participants using Mann-Whitney U-test.

| Question | Sector | Mean Rank | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing his military uniform | Civilian | 499.38 | 0.000 |

| Military | 433.69 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private / personal information with a doctor in his military uniform | Civilian | 490.49 | 0.006 |

| Military | 443.71 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information / explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing his military uniform | Civilian | 489.16 | 0.010 |

| Military | 445.21 | ||

| I feel that patient / doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing his military uniform | Civilian | 496.48 | 0.001 |

| Military | 436.96 | ||

| I prefer my doctor to be wearing civilian attire | Civilian | 430.28 | 0.000 |

| Military | 511.58 | ||

| I feel more comfortable sharing private/personal information with a doctor in a civilian attire | Civilian | 437.53 | 0.000 |

| Military | 503.41 | ||

| I feel more comfortable asking for further information/explanation or raise concerns when my doctor is wearing civilian attire | Civilian | 444.07 | 0.002 |

| Military | 496.04 | ||

| I feel that patient/doctor confidentiality is more respected with a doctor wearing civilian attire | Civilian | 443.93 | 0.002 |

| Military | 496.2 |

Generally, numerous studies have found that patients prefer their doctors to be dressed formally, including a white coat [10,11,13,15,17-20]. However, in some studies performed in the settings of orthopedics as well as obstetrics and gynecology, participants preferred their doctors to be wearing scrubs [14,21]. Nevertheless, most evidence supports that dress preferences have a limited impact on patients’ satisfaction, as well as the confidence in physicians’ ability and the level of their medical knowledge and expertise [8,9,11,14,22]. On the other hand, some studies found that patients’ comfort and confidence are influenced by their doctors’ attire [10,17,19,23].

There has been little research evaluating the effect of civilian versus military attire on patients’ perceptions of their healthcare providers. McClean et al tested whether military uniforms might affect patients’ perceptions towards their treating doctors and found that the clinicians’ attire does not adversely influence these perceptions [24]. In another study that was carried out in an obstetrics and gynecology clinic at the Naval Medical Center Portsmouth, Niederhauser et al found that female patients generally do not have a preference for specific physician attire [7]. However, they argued that a physician’s ability to optimally manage and treat an activeduty patient would be significantly affected since military uniform may negatively impact the patient’s ability to communicate his or her personal medical information freely with their healthcare provider [7]. They explained that such a barrier may be formed due to differences in military rank between the physician and the patient, which makes patients less comfortable with discussing personal information with their doctors [7].

Overall, male participants, military personnel, Kuwaiti nationals, non-commissioned officers, and individuals with lower educational qualifications preferred doctors in civilian attire. In this study, the respondents were 69% male, 72% Kuwaiti, 38% high-school educated or below, and 61% noncommissioned officers. Since the Kuwaiti military service members are exclusively male, our results may indicate a barrier in the doctor-patient relationship that is formed due to the military hierarchy. Another piece of information that supports this finding is that most treating doctors in the healthcare facilities examined are officers.

Figure 1:The overall responses of participants to the statements are shown in table 1. The column number (x-axis) represents the corresponding statement in table 1.

There has been limited research evaluating professional attire preferences in the Middle East and North-Africa region. In a study performed in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, patients expressed a preference for doctors to be dressed formally, including a tie, shirt, trousers, and white coat for males and long skirts for females [8]. Al-Ghobain et al explained that such formal attire was an indication of physicians’ medical professionalism and respect toward their patients [8].

The issue of health service providers’ attire is contextspecific. Despite the numerous pieces of evidence that support the preference of formal attire in an OPD setting, there have been some contradicting observations in an acutecare setting, where there was less preference for traditional attire [8,25]. Some evidence suggests that professionals gave more importance to attire than patients [11,26].

Some researchers have shown that irrespective of how a doctor is dressed, professionalism, neat grooming, and a clear name tag are found to be important [12,25,27]. There is evidence suggesting that a friendly manner, like having a smiling face, might be more important than what a provider is wearing [28]. Brandt explains, “There is no substitute for a gentle, concerned physician with an engaging, friendly, empathic demeanor [12].”

Limitations

This study had several limitations. Similar to previous studies, this study evaluated a small section of a much larger spectrum of personal attire and grooming choices [27]. Additionally, since attire preferences are contextrelated and culture sensitive, the findings of this study cannot be generalized to other healthcare settings. This study only looked at patient attitudes regarding the attire of doctors working in the OPD. Moreover, since this study was performed in a military healthcare setting, the attitudes of respondents may differ from the attitudes in civilian settings, as noted in previous studies [9].

Conclusion

The trust that patients invest in their physicians may be influenced by the respect they give and receive from them. This may explain why the study population did not have a particular preference regarding their doctor’s attire. A group of patients may have higher respect for military uniforms, while another group may prefer civilian attire. This may suggest that the main factor is the doctor-patient relationship and not necessarily the physician’s attire.

Nowadays, doctors typically wear shirts and ties to look professional and neat without possibly intimidating patients with military uniforms. It is important to understand the level of preexisting stress that patients may already have before entering the physician’s room. Therefore, any factor that can psychologically alleviate this stress should be considered.

According to a wide range of studies and the present findings, doctors’ attire, regardless of civilian or military, may not be the most concerning factor regarding the patient’s reactions. The general attitude of doctors and how they present themselves as professionals (experienced, trustworthy, and empathic) seem to have positive psychological effects on the patient’s reactions and willingness to share their medical condition with full honesty. It is for this reason that further investigation of the psychological impact of doctor’s attire is highly recommended.

Chue P (2006) The relationship between patient satisfaction and treatment outcomes in schizophrenia. Journal of Psychopharmacology 20: 38-56. [ Ref ]

Kennedy GD, Tevis SE, Kent KC (2014) Is there a relationship between patient satisfaction and favorable outcomes? Annals of surgery 260: 592. [ Ref ]

Doyle C, Lennox L, Bell D (2013) A systematic review of evidence on the links between patient experience and clinical safety and effectiveness. BMJ open 3: e001570. [ Ref ]

Bakar ZA, Fahrni ML, Khan TM (2016) Patient satisfaction and medication adherence assessment amongst patients at the diabetes medication therapy adherence clinic. Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome: Clinical Research & Reviews 10: S139-S43. [ Ref ]

Petrilli CM, Mack M, Petrilli JJ, Hickner A, Saint S, et al. (2015) Understanding the role of physician attire on patient perceptions: a systematic review of the literature— targeting attire to improve likelihood of rapport (TAILOR) investigators. BMJ Open 5: e006578. [ Ref ]

Kamata K, Kuriyama A, Chopra V, Saint S, Houchens N, et al. (2020) Patient preferences for physician attire: a multicenter study in Japan. J Hosp Med 15: 204-210. [ Ref ]

Niederhauser A, Turmer MD, Chauhan SP, Magann EF, Morrison JC (2009) Physician attire in the military setting: does it make a difference to our patients? Military Medicine 174: 817-820. [ Ref ]

Al-Ghobain MO, Al-Drees TM, Alarifi MS, Al-Marzoug HM, Al-Humaid WA, et al. (2012) Patients’ preferences for physicians’ attire in Saudi Arabia. Saudi Medical Journal 33: 763-767. [ Ref ]

Edwards RD, Saladyga AT, Schriver JP, Davis KG (2012) Patient attitudes to surgeons’ attire in an outpatient clinic setting: substance over style. The American Journal of Surgery 204: 663-665. [ Ref ]

Rehman SU, Nietert PJ, Cope DW, Kilpatrick AO (2005) What to wear today? Effect of doctor’s attire on the trust and confidence of patients. The American journal of Medicine 118: 1279-1286. [ Ref ]

Bearman G, Bryant K, Leekha S, Mayer J, Munoz-Price LS, et al. (2014) Healthcare personnel attire in non-operating-room settings. Infection control and hospital epidemiology 35: 107-121. [ Ref ]

Brandt LJ (2003) On the value of an old dress code in the new millennium. Archives of internal medicine 163: 1277-1281. [ Ref ]

Gherardi G, Cameron J, West A, Crossley M (2009) Are we dressed to impress? A descriptive survey assessing patients’ preference of doctors’ attire in the hospital setting. Clinical medicine 9: 519-524. [ Ref ]

Cha A, Hecht BR, Nelson K, Hopkins MP (2004) Resident physician attire: does it make a difference to our patients? American Journal of obstetrics and gynecology 190: 1484-1488. [ Ref ]

Chung H, Lee H, Kim HS, Lee H, Park HJ, et al. (2012) Doctor’s attire influences perceived empathy in the patient–doctor relationship. Patient Education and Counseling 89: 387-391. [ Ref ]

Fischer RL, Hansen CE, Hunter RL, Veloski JJ (2007) Does physician attire influence patient satisfaction in an outpatient obstetrics and gynecology setting? American Journal of obstetrics and gynecology 196: 186.e1-5. [ Ref ]

Kurihara H, Maeno T, Maeno T (2014) Importance of physicians’ attire: factors influencing the impression it makes on patients, a cross-sectional study. Asia Pacific Family Medicine 13: 2. [ Ref ]

Gallagher J, Stack J, Barragry J (2008) Dress and address: patient preferences regarding doctor’s style of dress and patient interaction. Irish medical journal 101: 211-213. [ Ref ]

Sotgiu G, Nieddu P, Mameli L, Sorrentino E, Pirina P, et al. (2012) Evidence for preferences of Italian patients for physician attire. Patient prefernce and adherence 6: 361-367. [ Ref ]

Yonekura CL, Certain L, Karen SKK, Alcantara GAS, Ribeiro LG, et al. (2013) Perceptions of patients, physicians, and Medical students on physicians’ appearance. Revista da associacao medica Brasileira 59: 452-459. [ Ref ]

Jennings JD, Ciaravino SG, Ramsey FV, Haydel C (2016) Physicians’ attire influences patients’ perceptions in the urban outpatient orthopaedic surgery setting. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research® 474: 1908-1918. [ Ref ]

Kersnik J, Tusek-Bunc K, Glas KL, Poplas-Susie T, Vodopivec-Jamsek V (2005) Does wearing a white coat or civilian dress in the consultation have an impact on patient satisfaction? European journal of general practice 11: e031887. [ Ref ]

Hartmans C, Heremans S, Lagrain M, Van Asch K, Schoenmakers B (2014) The Doctor’s New Clothes: Professional or Fashionable? Primary health care 3: 1-5. [ Ref ]

McLean C, Patel P, Sullivan C, Thomas M (2005) Patients’ perception of military doctors in fracture clinics—does the wearing of uniform make a difference? Journal of the Royal Naval Medical Service 91: 45-47. [ Ref ]

Au S, Khandwala F, Stelfox HT (2013) Physician attire in the intensive care unit and patient family perceptions of physician professional characteristics. JAMA internal medicine 173: 465-467. [ Ref ]

Bianchi MT (2008) Desiderata or dogma: what the evidence reveals about physician attire. Journal of General Internal Medicine 23: 641-643. [ Ref ]

Baevsky RH, Fisher AL, Smithline HA, Salzberg MR (1998) The influence of physician attire on patient satisfaction. Academic emergency medicine 5: 82-84. [ Ref ]

Lill MM, Wilkinson TJ (2005) Judging a book by its cover: descriptive survey of patients’ preferences for doctors’ appearance and mode of address. BMJ 331: 1524-1527. [ Ref ]