Journal Name: Journal of Health Science and Development

Article Type: Research

Received date: 30 December, 2019

Accepted date: 29 January, 2020

Published date: 2021-01-30

Citation: Woudneh AF (2020) Determinants of Progression Rate of Hepatitis B Virus in the Liver of Patients: A Prospective Longitudinal Study. J Health Sci Dev Vol: 3, Issu: 1 (22-29).

Copyright: © 2020 Woudneh AF . This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Hepatitis B is the most common liver infection in the world which is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). The virus can attack and injure the liver. The infection of hepatitis B virus leads to chronic viral hepatitis infections in hundreds of millions of people in worldwide. The objective of current study was to identify factors that affect the progression rate of hepatitis B virus in patients’ liver who were treated at Felege-Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital, during treatment period.

Methods: The data for this study was obtained from hepatitis B patients chart registered for treatment during January 2013 to December 2016 at chronic hepatitis B patients’ clinic at Felege-Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. The analytical methodology used in current investigation was the linear mixed effect model. The estimation of the model parameters was done by Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) procedures.

Results: From the linear mixed effect model, main effects like visiting time (p-value < 0.001), sex(p-value = 0.0332), age (p-value < 0.001), vaccination history (p-value = 0.0141), marital status (p-value = 0.0032), Alanine amino-transferase (p-value = 0.0057), Genotype, A (p-value = 0.0154), Genotype, B (p-value = 0.0183), Genotype, C (p-value = 0.0143) and Albumin (p-value = 0.0329) significantly affected the variable of interest. Similarly, interaction effects of time with marital status (p-value = 0.0042) played statistically significance role on the progression rate of hepatitis B virus in the liver of patients.

Conclusion: A certain groups which are at maximum risk and needs intervention have been identified. Highly concrete evidences have been increased from time to time for certain population with chronic HBV infection being at great risk for progression of liver disease. Hepatitis B virus infected patients at the study area should have information about factors that can affect the progression rate of HBV. Ministry of health or health staff should aware the community to take vaccination that helps to protect individuals from hepatitis B virus.

Keywords:

Hepatitis B patients, Infectious disease, Liver disease, Virus, Linear mixed model, REML.

Abstract

Background: Hepatitis B is the most common liver infection in the world which is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV). The virus can attack and injure the liver. The infection of hepatitis B virus leads to chronic viral hepatitis infections in hundreds of millions of people in worldwide. The objective of current study was to identify factors that affect the progression rate of hepatitis B virus in patients’ liver who were treated at Felege-Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital, during treatment period.

Methods: The data for this study was obtained from hepatitis B patients chart registered for treatment during January 2013 to December 2016 at chronic hepatitis B patients’ clinic at Felege-Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. The analytical methodology used in current investigation was the linear mixed effect model. The estimation of the model parameters was done by Restricted Maximum Likelihood (REML) procedures.

Results: From the linear mixed effect model, main effects like visiting time (p-value < 0.001), sex(p-value = 0.0332), age (p-value < 0.001), vaccination history (p-value = 0.0141), marital status (p-value = 0.0032), Alanine amino-transferase (p-value = 0.0057), Genotype, A (p-value = 0.0154), Genotype, B (p-value = 0.0183), Genotype, C (p-value = 0.0143) and Albumin (p-value = 0.0329) significantly affected the variable of interest. Similarly, interaction effects of time with marital status (p-value = 0.0042) played statistically significance role on the progression rate of hepatitis B virus in the liver of patients.

Conclusion: A certain groups which are at maximum risk and needs intervention have been identified. Highly concrete evidences have been increased from time to time for certain population with chronic HBV infection being at great risk for progression of liver disease. Hepatitis B virus infected patients at the study area should have information about factors that can affect the progression rate of HBV. Ministry of health or health staff should aware the community to take vaccination that helps to protect individuals from hepatitis B virus.

Keywords:

Hepatitis B patients, Infectious disease, Liver disease, Virus, Linear mixed model, REML.

Background

Hepatitis B is the most common liver infection in the world. It is caused by the hepatitis B virus (HBV) (a small DNA virus), which can attack and injure the liver. This hepatitis B virus infection leads to chronic viral hepatitis infections in hundreds of millions of people worldwide, with possibly fatal health consequences. The highly infectious virus particles in the blood of infected individuals pose a serious health risk, with healthy asymptomatic carriers of the main reservoir of infection [1,2].

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) define three phases of chronic HBV infection that are now widely accepted: the immune tolerant phase, the immune active phase and the inactive hepatitis B phase [3,4]. In the immune tolerant phase, HBV-infected persons are HBeAg-positive, have normal ALT levels and elevated levels of HBV DNA that are up to 20,000 IU/ML and commonly well above 1 million IU/ML [4] . The immune active phase is characterized by elevated ALT levels and an elevated HBV DNA level with at least 2000 IU/ML [5]. The inactive hepatitis B phase is characterized by the absence of HBeAg and the presence of anti-HBe, normal ALT levels, HBV DNA re-activation of anti- HBe- positive chronic hepatitis appear to be at higher risk of developing HCC or cirrhosis [6,7].

Exhibition and experience of symptoms vary greatly between infected individuals: one-third has sub-clinical infection without any symptoms; one‐third experiences a mild “flu-like” illness with symptoms like malaise, vomiting, nausea and mild fever and the remaining one‐third exhibits yellowing of the skin and eyes (jaundice), bilirubinuria (the dark urine caused by the jaundice), extreme fatigue, anorexia, right‐sided upper abdominal pain and an inflamed tender liver. About 90% of adults recover completely, although this may require at least six months with continual tiredness and prejudice to alcohol [8,9].

In an infected individual, HBV is detectable in the blood and body fluids such as semen and vaginal secretions (concentration about 1000 IU / ML). A diagnosis of hepatitis B is based on the detection of the various viral antigens and antibodies in the blood or fluid: hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) and antibody (anti-HBs), hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) and antibody (anti-HBc IgM and anti‐HBc IgG), hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) and antibody [10,11].

The hepatitis B virus spreads through contact with infected body fluids. Its modes of transmission are comparable to those of HIV, but HBV are 50 to 100 times more infectious [11]. It can be transmitted at 3 stages in life; around the time of birth, during childhood, and in adult life .It is usually transmitted by contact with the blood, semen or vaginal secretions of an infected (HBV DNA-positive or HBsAg-positive) person. The virus must be introduced through mucous membranes or broken skin for infection to be occurred [11].

Hepatitis B is a serious communal health problem throughout the world and caused by Hepatitis B virus (HBV) and hence at risk of developing active hepatitis B disease. According to the WHO Global report, up to 2 billion people worldwide have been infected with HBV; about 350 million people live with chronic HBV infection, and about 600,000 people die from HBV-related liver disease or HCC each year [12]. Hepatitis B places a heavy burden on the health care system such as high costs of treatment, liver treatment failure and chronic liver disease. In many countries, hepatitis B is the leading cause of liver transplants [13]. Treatments at the end-stages are expensive, easily reaching up to hundreds or thousands of dollars per person [14]. Hepatitis B is one of the major diseases of mankind and is a serious global public health problem [15]. Of the 2 billion people who have been infected with the HBV, more than 350 million have chronic permanent infections. HBV infections result in 500,000 to 1.2 million deaths per year. The risk of infection becomes chronic for 90 % of infants, 30 % of children aged < 5 years and 2.6 % for adults [15].Countries like Japan, India, central Asia and the Middle East including Eastern and Southern Europe, as well as parts of South America, are all areas with intermediate (2% to 7% HBsAg- positive) prevalence of chronic HBV infection. Low prevalence (< 2% HBsAgpositive) of chronic HBV is found in countries including the United States, Northern Europe, Australia, and the Southern part of South America [15,16].

In Africa, infections with chronic HBV play a major role in the etiology of most liver diseases. By country, estimated HBsAg sero-prevalence ranges between 5% and 19%, and the total number of carriers may approach 58 million with as many as 12.5 million likely to die prematurely due to hepatitis B-induced liver disease [11,17].

A nationwide epidemiological study about hepatitis B marker prevalence was conducted in Ethiopia on 5,270 young males from all regions of the country [17]. Overall prevalence rate was 10.8% for HBsAg and 73.3% for “at least one marker positive”; a remarkable geographical and ethnic variability of marker prevalence was observed which reflects the wide differences existing in Ethiopia in sociocultural, environment and activities such as tribal practices and traditional surgery [15]. Sexual practices and medical exposure also play some role as determinants of hepatitis B marker prevalence in Ethiopia [17]. Chronic viral hepatitis also results in loss of productivity [18]. Studies so far lead us to consider that different genotypes may be linked with different rates of development from acute to chronic HBV infection. However, different hosts and environmental factors make certain difficulties to extrapolate findings from one geographical region to another. Hence, there are inconsistencies of findings obtained from different investigations. Some of the researches conducted previously were cross-sectional and there was no chance of observing repeated observations for each subject [19]. One of the previous research recommended that it is important to conduct a well design, prospective longitudinal study to identify predictors of disease progression in which it helps to guide treatment strategy of the disease [17]. Therefore, the current investigation was conducted with objective of identifying the risk factors for the progression rate of hepatitis B virus (HBV) in the liver of HBsAg- positive patients using HBV DNA level (viral load) of patients observing the same subject repeatedly.

Methods

Study materials and settings

The data for current investigation consists of secondary data, records of social, demographic and clinical characteristics of 409 hepatitis B virus patients recorded for 36 months (3 year) of treatment. The data was collected by health care service providers at Felege Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital. Linear mixed effect model was used to assess predictors of the variable of interest. The study was longitudinal prospective, targeted for 2035 moderate hepatitis B virus patients at the hospital under the followups from January 2013 to December 2016.

Inclusion criteria

Hepatitis B patients admitted to adhere medication with at least six months follow-ups and whose viral loads were recorded at each visiting time were included in the investigation.

Sample size and sampling technique

Out of the targeted hepatitis patients, 409 were selected using purposive sampling technique where patients included in the investigation should have viral load records at every follow-up. In sample size computation, 95% confidence limit and 5 % marginal errors were taken in to consideration.

Data collection tools and procedures

The available data at the hospital was first observed and discussed with health care service providers. Data was extracted using data extracted format developed by the investigators in consultation to health care providers. All relevant information from the cards of patients was collected by health care service providers after theoretical and practical orientations by the investigators. Charts of patients were retrieved using patients’ registration card number that indicates patients whose viral loads were also recorded. This was done in the electronic data base system.

Quality of data

The quality of data was controlled by data quality controllers from the specific section of the hospital and regional laboratory center where viral load of patients were conducted. Data collectors got orientation about the variables included in the investigation. The data extraction tools and variables included under investigation were pretested for consistency of understanding, review of tools and completeness of the required information on 50 hepatitis B virus patients before final data collection. Based on the information from the Pilate test, necessary amendments were made on the final data collection format. The retrieval process in data collection was closely monitored by the investigators in the whole data collection period. Bothe of the predictor and variable of interest were checked regularly for their completeness of information. Any inconvenience related to data collection was immediately communicated to data collectors and corrective measures were taken.

Patients in the hospital

All patients registered at the hospital were followed up in the era of their course of treatment to assess treatment outcome. Based on treatment outcomes, patients were classified as: cured (finished treatment with negative bacteriology result at the end of the treatment (HBsAgnegative, HBeAg-negative), treatment completed (finished treatment but without bacteriology result at the end of their treatment), Patients were provided with free HB medications for a period of up to 6 months in the hospital. If patients, after the 6 months follow-ups are not cured, they are referred as chronically infected by HBV. These patients were followed up regularly until completion of their treatment. Patients who were treated for at least 6 month in the hospital were included under this investigation.

Variables included in current investigation

The response variable: The response (dependent) variable was number of HBV DNA unit expressed in IU/ML. It is represented by yi and it measures the number of HBV DNA also known as viral load and it indicates how rapidly the virus is reproducing itself in the liver. This procedure measures how many HBV DNA units are found in a milliliter or about one drop of blood.

Predictor variables: predictor variables included under current study were Sex (Male, Female), Age in years, Coinfection (HIV, HCV, Others, No), Genotype (A, B, C, Others), Marital status (Living with partner, Living without partner), History of vaccination (No, Yes), Baseline ALT level (Normal, Elevated), HBV genotype (A, B, C, Others), Albumin level and number of visiting times.

About the model: A linear mixed model (LMM) is a parametric linear model for longitudinal or repeatedmeasures that quantifies the relationships between a continuous dependent variable and various predictor variables. A LMM may include both fixed-effect parameters associated with one or more continuous or categorical covariates and random effects associated with one or more random factors. Fixed-effect parameters describe the relationships of the covariates to the dependent variable for entire population; random effects are specific to subjects within a population. Consequently, random effects are directly used in modeling the random variation in the dependent variable at different levels of the data [19,20].

The linear mixed-effects model assumes that the observations follow a linear regression where some of the regression parameters are fixed or the same for all subjects, while other parameters are random or specific to each subject [18,20]. Meanwhile, population parameters, individual effects and within-subject variations make up the first stage of the model [21]. Correlated continuous outcomes are treated as fixed effects. The general form of the linear mixed-effects model after combining the two stages is approximately normal [20-22].The two stage of the model are indicated as follows [23].

First stage of the model belongs to individual response Yij for ithsubject, measured at time tij,i = 1,− − −, n : j = 1,− − −, ni response vector Yi for ith subject: Yi = Ziβi + εi Where, Yi=(Yi1,Yi2,---,Yini)T Zi is an ni ×q matrix of known covariates, βi is q dimensional vector of subject specific regression coefficients. , often this model describes the observed variability with in subjects. Second stage describes the between subject variability that explains in the subject specific regression coefficients using known covariates. Ki is a q× pmatrix of known covariates, β is a P dimensional vector of unknown regression parameter bi ~ N (0, D) Combining the two stages (1) & (2) one can have: Let Xi = Zi Ki in (3), then the general form of the model is expressed as: Yi = Xi βi + Zi bi+ εi (4) Where Yi represents a vector of continuous responses for the ith subject, Xi is an i n × p design matrix, which represents the known values of the p covariates.

In data analysis, restricted maximum likelihoods (REMLs) were used for parameter estimation and for the purpose of model selection, AIC and other information criterion were used. After final model selection, the model was refitted using REML estimation methods such [20-22]. Likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) were used to compares two models, the full model with all of the interactions and the reduced model with just a subset of terms [24]. In model selection, methods of model selection was carried out [21,25]. The variance covariance structure with the lower AIC value had been considered as an appropriate to select the model. Finally, the individual Wald test had been taken in to consideration.

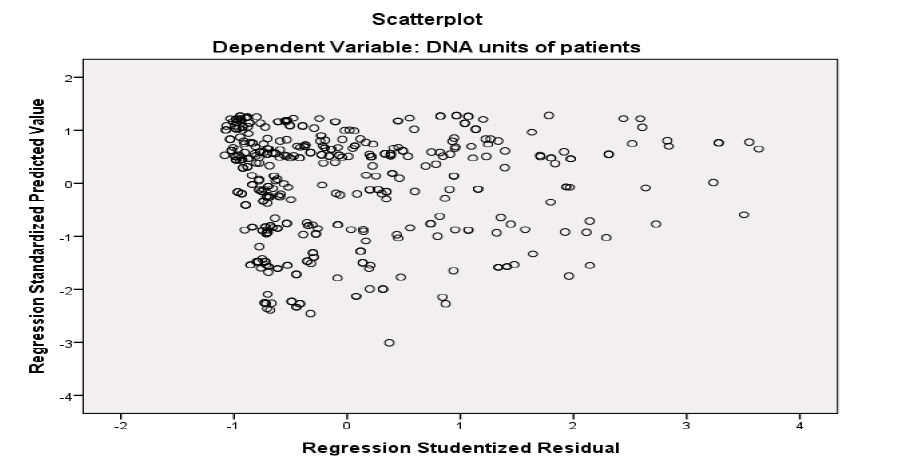

Figure 1:The scatter plot of residuals.

Results

The medical cards of 409 patients have been reviewed, of which 57.9 % (total 237) of patients were moderate (>1000 IU/ML), and 42.1% (172) of patients were chronic (>2000 IU/ML) level of HBV replication in their liver. The base line characteristics for current investigation are given in table 1.

The data for its normality was assessed using the Q-Q plot. The Q-Q plot indicates that the ordered data of the observed value versus the expected normal probability satisfied the assumption of normality. The normality assumption was also checked for random effects as indicated in figure 1.

From figure 1, since the scatter plot of the residual is random it implies that the random term is normally distributed and it is possible to conclude that the error term for fixed effect is also normally distributed

Certain covariance structures were compared to select the one appropriate to the given data. Some of the covariance structures used for model selection were; unstructured (UN), compound symmetric (CS), first-order autoregressive (AR (1)) and Toeplitze (Toep). Table 2 displays the corresponding fit statistics of the structures obtained from the Newton-Raphson algorithm.

As it is indicated in table 2, AR (1) had smallest information criterion hence, the covariance structure used for data analysis was AR (1).

Model parameter estimation

Restricted maximum likelihood was used for parameter estimation and this was used as a default SAS program. The analysis for type 3 tests and solutions for the fixed effects are indicated at table 3 and table 4 respectively.

Significant predictor covariates from table 3 were selected for further analysis in fixed and random components of the linear mixed model used for data analysis. The multivariate data analysis is indicated in table 4.

Table 1:Categories of qualitative predictor variables used in current investigation.

| Variables | Categories | n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | Male | 215(52.6) |

| Female | 194 (47.4) | |

| History of drug use, HDU | YES | 194 (47.4) |

| NO | 215(52.6) | |

| ALT | Elevated | 226 (55.3) |

| Normal | 183(44.7) | |

| Co-infected with | HCV | 69 (16.9) |

| HIV | 54 (13.2) | |

| N0 | 110 (26.9) | |

| Other | 176(43.0) | |

| Marital status | Living with partner | 172 (42.1) |

| Living without partner | 237 (34.0) | |

| Genotype | A | 60 ( 14.7) |

| B | 108 (26.4) | |

| C | 95 (23.2) | |

| Others | 146 (35.7) |

Table 2:Information criterion used for selection of covariance structure.

| Information criterion | un | CS | TEOPLZ | AR(1) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AIC (smaller is better) | 53521.6 | 50204.6 | 54079.9 | 49835.5 |

| AICC (smaller is better) | 53521.6 | 50204.6 | 54080.5 | 49835.5 |

| BIC (smaller is better) | 53521.6 | 50194.6 | 54029.9 | 49827.5 |

| Average CCC | -0.2341 | -0.6710 | 0.4904 | 0.9709 |

Table 3:Type 3 data analysis for univariate potential covariates.

| Effect | DF | F Value | Pr.> F |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time | 1 | 253.28 | <.0001* |

| Sex | 1 | 0.12 | 0.1732 |

| Age in years | 1 | 28.38 | <.0001* |

| HDU | 1 | 0.11 | 0.1741 |

| ALT | 1 | 7.67 | 0.0057* |

| Co infection | 3 | 1.01 | 0.2386 |

| Mar. Status | 2 | 12.81 | <.0001* |

| Genotype | 3 | 0.88 | 0.0449* |

| Albumin | 1 | 4.56 | 0.0329* |

| time*Marital status | 2 | 13.51 | <.0001* |

| time*genotype | 3 | 11.94 | <.0001* |

| time*Albumin | 1 | 9.27 | 0.0024* |

| time*Marital status*co infection | 6 | 2.55 | 0.0184* |

Table 4 indicates that for one unit increase of visiting time, the average HBV of hepatitis B patients decrease by 2.9 IU/ML (p-value < 0.001) that means on average the replication of hepatitis B virus inside the liver of patients was decreased with increase of visiting time. However, as age of patients increased by one year, the average hepatitis B virus DNA unites is also increased by 3.59 IU/ML (p-value < 0.001). The average HBV DNA for patients with elevated ALT (Amino Liver Transfers) level was increased by 4.24 IU/ ML (p-value 0.0057) as compared to that of a patient with a normal ALT level.

The progression rate of HBV DNA for HIV infected patients was increased by 3.47 IU/ML (p-value = 0.0434) as compared to HIV-negative HBV patients. The average change of HBV DNA for patients with genotype A was increased by 6.03 IU/ML (p-value = 0.0154) as compared to that of the patients with other genotypes, however, the rate of change of average HBV DNA unite for patients with genotype B was decreased by 2.91 IU/ML(p-value = 0.0183) when compared to patients with other genotypes. Similarly, the average change of HBV DNA units for patients with genotype C was decreased by 3.77 IU/ML (p-value = 0.0143) as compared to other genotypes. The progression rate of hepatitis B virus for patients living with partners was increased by 2.72 IU/ML (p-value = 0.0032) when compared to patients living without partners. As the amount of Albumin in hepatitis B patients increased by one unit, the progression rate of hepatitis B virus decreased by 3.4 IU/ML ( p-value = 0.0329), keeping the other things constant. The average progression rate of HBV units for patients who took vaccination at childhood was decreased by 5.74 (p-value = 0.0141) as compared to those patients who did not take vaccination related to HBV at child age.

Table 4:Multivariate parameter estimates for fixed effects.

| Effect | Estimate | Standard error | t -value | Pr>|t| |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| intercept | 54.32 | 3.78 | 11.40 | <.0001* |

| time | -2.90 | 2.00 | -7.26 | <.0001* |

| Sex(Reference = Male) | ||||

| Female | 5.54 | 4.62 | 0.34 | 0.1732 |

| age | 3.59 | 7.87 | 5.33 | <.0001* |

| Vaccination for HBV at child age (Reference=No) | ||||

| Yes | -5.74 | 1.02 | -0.33 | 0.0141* |

| ALT(Reference = Normal ) | ||||

| EL | 4.24 | 1.45 | 2.77 | 0.0057* |

| Co infection (Reference = others) | ||||

| HCV | 2.66 | 6.96 | 0.65 | 0.1512 |

| HIV | 3.47 | 4.36 | 0.78 | 0.0434* |

| NO | -2.39 | 2.80 | -0.53 | 0.1595 |

| Marital status(Reference = living without partners) | ||||

| Living with partners | 2.72 | 2.56 | 2.95 | 0.0032* |

| Genotype (Reference = other) | ||||

| A | 6.03 | 1.25 | 3.03 | 0.0154* |

| B | -2.91 | 1.67 | -1.33 | 0. 0183* |

| C | -3.77 | 2.24 | -0.46 | 0.0143* |

| Albumin | -3.40 | 3.66 | -2.14 | 0.0329* |

| Time*Marital status (Reference = Living without partner ) | ||||

| Living with partner | 3.94 | 6.22 | 2.86 | 0.0042* |

The interaction effect of time with marital status had significant effect on current investigation.

Hence, as visiting time of a patient increased by one unit, the rate of change of average HBV DNA unit for patients living with partners was increased by 3.94 IU/ML (p-value = 0.0042 ) as compared to those patients living without partners.

Discussion

For those patients who followed-up their prescribed medication by the health staff reduce the progression rate of HBV. This indicates that the disease can be cured for patients with close follow-ups keeping the other things like drug resistance constant. A hepatitis B infected patient, who adhered the prescribed medication achieved and maintained undetectable HBV DNA unit with progressively increasing rates of ALT normalization. This result is supported by one of the previous studies [26].

Female HBV infected patients had more progression rate of HBV as compare to males. This might be the reason that females are more exposed to the virus especially via sexual intercourse, another reason for this is that females may not have close follow-ups because of additional home works like child care and others [18].

Patients who had taken vaccination during child hood had low progression rate of HBV as compared to those who did not take vaccination. Hence, vaccination at child hood had a power of reducing its progression rate and prevents individuals from the disease [12,13].

Patients con-infected by HIV complicates the supervision of the progression rate of HBV infected individuals. On the one hand, liver-related measures, including hepatocellular carcinoma, come into view regularly in co-infected patients than in HBV-mono-infected individuals [3]. Suppression of HBV duplication by treatment with anti-HBV agents represents the paramount way to avoid series of liver disease in these patients [27]. Alternatively, the use of antiretroviral agents to treat HIV-associated immunodeficiency becomes challenged by an increased risk of hepatotoxicity in subjects with underlying chronic hepatitis B [3]. Absolute suppression of HBV viremia is also important to reduce resistance of the virus as the risk of resistance positively correlates with viral load [26]. In HIV-positive patients with chronic hepatitis B, the recognition that low CD4 counts are connected with HBV viremia may further support recent guidelines that recommend to bearing in mind an earlier introduction of antiretroviral therapy including anti-HBV agents in HIV/ HBV-co-infected individuals [11].

There is a strong association between HBV genotype-A infection and HBV progression. HBV infected patients with genotype-A have high progression rate as compared to other genotypes. This is a predictable result, since 50% of genotypes other than A were also HCV anti-body positive and it is remarkable that HBV genotype-A patients tended to demonstrate significantly higher serum HBV DNA levels, irrespective of anti-HBV drug experience [10,27]. This is important since HBV viremia is connected with the risk of liver-related complications and selection of HBV drug resistance [28]. Delta hepatitis occurred more repeatedly in HBsAg-positive patients carrying HBV genotypes other than A as compared to those infected with genotype-A, because there is a strong separation of HBV genotypes by risk group category [16]. Serum HBV DNA viremia was lower and more often undetectable in HBsAg-positive patients with delta hepatitis than in the rest, given the inhibitory effect on HBV replication caused by HDV super infection [29]. Given the dependence of HDV on HBV, and that delta hepatitis is the most aggressive form of chronic viral hepatitis, it is of great interest to clarify to what degree potent anti-HBV oral drugs may be of benefit in ameliorating the excessive liver damage caused by hepatitis delta in HIV/HBV-co-infected patients [30].

As visiting times of patients increased, the progression rate of hepatitis B virus is decreased and becomes undetectable for patients living without partners as compared to those patients living with partners. The reason for this, might be HBV infected patients living with partners make sexual intercourse and this makes infection and facilitates the progression rate of the virus [31].

Conclusion and Recommendation

The result under this investigation indicates that, age, sex, genotype, history of co-infection, whether or not patients took vaccination at childhood and follow-up times played significant role for the progression rate of HBV DNA unit. Therefore, more attention should be given for aged patients, for females, for HBV infected and HIV positive individuals, for individuals who did not take vaccination at childhood and ALT elevated patients. The health care workers should always measure the baseline Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) level and the baseline hepatitis B virus deoxyribonucleic acid of patients and must know the baseline age of patients when they come to the hospital for the first time in order to control the replication of the virus inside patients’ liver. Policy makers should implement different HBcAg screening techniques and vaccination programs (with HBV protection monitoring) for individuals at child age. The health staff at health institution should register full personal information of patients that are used to reduce from factors which make faster progression rate of hepatitis B virus. Further investigation including all other potential cases for progression rate of hepatitis B virus which are not included under current investigation is important to have additional information.

This study was not without limitation; one such limitation is that the sample was taken in one treatment center. Taking samples from different centers may have results different from the current result. Moreover, HBV e antigen status was unidentified, and this might have a certain influence on viral load assessment, regardless of the HBV genotype. Including all potential predictors may provide additional information about predictors of the variable of interest. Despite this, as far as our knowledge is concerned, the current study is the largest virological description of HBV DNA unit conducted so far in study area using longitudinal or repeated observations on the same individual who provides a chance of observing repeated response from each subject and this approves the consistency of results on each patient.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable

Consent to publish

Not applicable

Availability of data and materials

The secondary data, which is available with the author, will not be made available publically due to concerns about protecting participants’ identity and respecting their rights to privacy. At the time, the data was collected; informed consent form was not obtained from participants for publication of the dataset.

Competing interests

As no individual or institution funded this research, there was no conflict of financial interest between authors or between authors and institutions.

Funding

Not applicable.

Acknowledgement

Amhara Region Health Research & Laboratory Center at Felege-Hiwot Teaching and Specialized Hospital and all health staffs, is gratefully acknowledged for the data they supplied for our health research. A medical doctor, Dr. Belayneh, at medical college of Bahir Dar university is also highly acknowledged for his proper description of medical terminologies under this investigation.

McGlynn KA, Petrick JL, London WT (2015) Global epidemiology of hepatocellular carcinoma: an emphasis on demographic and regional variability. Clinics in liver disease 19: 223-238. [ Ref ]

Faizo, Arwa Ali A (2014) Prenatal screening of potential infectious diseases in Manitoba. [ Ref ]

Hoofnagle JH (2007) Management of hepatitis B: summary of a clinical research workshop. Hepatology 45: 1056-1075. [ Ref ]

Lok AS, Heathcote EJ, Hoofnagle JH (2001) Management of hepatitis B: 2000—summary of a workshop. Gastroenterology, 120: 1828-1853. [ Ref ]

McMahon BJ (2005) Epidemiology and natural history of hepatitis B. Seminars in liver disease 25: S1 1-3. [ Ref ]

De Franchis R (1993) The natural history of asymptomatic hepatitis B surface antigen carriers. Annals of internal medicine 118: 191-194. [ Ref ]

Detels R (2011) Oxford textbook of public health. Oxford University Press, UK. [ Ref ]

Weston D (2008) Infection prevention and control: theory and practice for healthcare professionals. John Wiley & Sons, NJ, USA. [ Ref ]

Mahoney FJ (1997) Progress toward the elimination of hepatitis B virus transmission among health care workers in the United States. Archives of Internal Medicine 157: 2601-2605. [ Ref ]

Hatzakis A (2011) The state of hepatitis B and C in Europe: report from the hepatitis B and C summit conference. Journal of Viral Hepatitis 18: 1-16. [ Ref ]

Amidu N (2012) Sero-prevalence of hepatitis B surface (HBsAg) antigen in three densely populated communities in Kumasi, Ghana. Journal of Medical and Biomedical Sciences 1: 59-65. [ Ref ]

Lavanchy D (2004) Hepatitis B virus epidemiology, disease burden, treatment, and current and emerging prevention and control measures. Journal of viral hepatitis 11: 97-107. [ Ref ]

Abebe A (2003) Seroepidemiology of hepatitis B virus in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: transmission patterns and vaccine control. Epidemiology & Infection 131: 757-770. [ Ref ]

Epidemic WHO (2002, 2013) Pandemic alert and response (EPR) for HCV. [ Ref ]

Mohammed Y (2014) Prevalence of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIB among chronic liver disease patients in selected hospitals. Addis Ababa University, Ethiopia. [ Ref ]

Koyuncuer A (2014) Associations between HBeAg status, HBV DNA, ALT level and liver histopathology in patients with chronic hepatitis B. Science Journal of Clinical Medicine 3: 117-123. [ Ref ]

Su J (2010) The impact of hepatitis C virus infection on work absence, productivity, and healthcare benefit costs. Hepatology 52: 436-442. [ Ref ]

Verbeke G, Molenberghs G (2009) Linear mixed models for longitudinal data: Springer Science & Business Media. [ Ref ]

Abate Assefa, Biniam Mathewos (2013) Hepatitis B and C Viral infections among blood donors at Bahir Dar, Ethiopia. International Journal of Medical Research & Health Sciences 2: 624-630. [ Ref ]

West BT, Welch KB, Galecki AT (2014) Linear mixed models: a practical guide using statistical software: CRC Press, USA. [ Ref ]

Laird NM, Ware JH (1982) Random-effects models for longitudinal data. Biometrics 38: 963-974. [ Ref ]

Davis Charles S (2002) Statistical methods for the analysis of repeated measurements: Springer Science & Business Media. [ Ref ]

Schabenberger O, Pierce F (2002) Linear mixed models for clustered data. Contemporary statistical models for the plant and soil sciences. CRC Press, New York. [ Ref ]

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow (1989) Applied Logistic Regression. John Wolfley Sons, USA. [ Ref ]

Hosmer DW, Lemeshow S (2000) Introduction to the logistic regression model. [ Ref ]

Park JG, Park SY (2015) Entecavir plus tenofovir versus entecavir plus adefovir in chronic hepatitis B patients with a suboptimal response to lamivudine and adefovir combination therapy. Clinical and molecular hepatology 21: 242-248. [ Ref ]

Jiang W (2009) Plasma levels of bacterial DNA correlate with immune activation and the magnitude of immune restoration in persons with antiretroviral-treated HIV infection. Journal of Infectious Diseases 199: 1177-1185. [ Ref ]

Kilaru K (2006) Immunological and virological responses to highly active antiretroviral therapy in a non‐clinical trial setting in a developing Caribbean country. HIV medicine 7: 99-104. [ Ref ]

Roezindu M (2013) Liver function test abnormalities in Nigerian patients with human immunodeficiency virus and hepatitis B virus co-infection. International journal of STD & AIDS 24: 461-467. [ Ref ]

Kim BG (2015) Tenofovir‐based rescue therapy for chronic hepatitis B patients who had failed treatment with lamivudine, adefovir, and entecavir. Journal of gastroenterology and hepatology 30: 1514-1521. [ Ref ]

Lau DTY, Bleibel W (2008) Current status of antiviral therapy for hepatitis B. Therapeutic advances in gastroenterology 1: 61-75. [ Ref ]