Journal Name: Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health

Article Type: Short Communication

Received date: 16 July, 2019

Accepted date: 30 July, 2019

Published date: 06 August, 2019

Citation: Miller J (2019) Unrelenting gynecological conflict: Isn’t it time we all got along? J Obstet Gynecol Womens Health Vol: 1, Issu: 1 (25-26).

Copyright: © 2019 Miller J. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Over the past twenty-five years, a rupture has emerged between what I will term ‘gynecological purists’ and ‘gynecological futurists’. Members of the orthodox camp (the ‘purists’) maintain the existence of the uterus, the reality of oophorectomy, and, ultimately, the hope that we shall all one day die and be admitted to the RCOG. The futurists reject each of these three claims, offering instead the vision of a bleak universe in which there is no uterus, no possibility of oophorectomy, and nothing on the other side of death. In this paper, I will argue that the purists and the futurists represent two sides of the same coin, though they fail to recognise the fact. While gynaecologists have spent the past two-and-ahalf decades debating the eternal, I have been constructing a new branch of gynecology which returns to more central questions: how are we to live? Is there such a thing as truth? And, if so, can we know it?

Over the past twenty-five years, a rupture has emerged between what I will term ‘gynecological purists’ and ‘gynecological futurists’. Members of the orthodox camp (the ‘purists’) maintain the existence of the uterus, the reality of oophorectomy, and, ultimately, the hope that we shall all one day die and be admitted to the RCOG. The futurists reject each of these three claims, offering instead the vision of a bleak universe in which there is no uterus, no possibility of oophorectomy, and nothing on the other side of death. In this paper, I will argue that the purists and the futurists represent two sides of the same coin, though they fail to recognise the fact. While gynaecologists have spent the past two-and-ahalf decades debating the eternal, I have been constructing a new branch of gynecology which returns to more central questions: how are we to live? Is there such a thing as truth? And, if so, can we know it?

The Purists

Following her publication of the Bhagavad Gita in 1957, Virginia Apgar became a recluse, restricting herself to a circle of two friends, one of which was a collection of chinaware. Over the coming years, Apgar restricted herself to a narrower and narrower circle of ideas, eventually reducing herself to one idea alone: the existence of the uterus. It was on the basis of this principle that Virginia Apgar nailed herself to a lamppost in Westfield. As she stood dying, her sister Cassandra asked her, ‘is there anything that you require?’ Dr Apgar replied, ‘Nothing but the womb.’

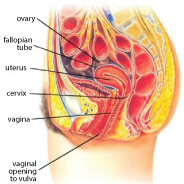

During the following decade, a bitter enmity was to develop between the descendants of Dr Apgar and the members of a rival school, the Futurists. For the latter part of her life, Dr Apgar had purchased tens of thousands of dollars of advertising space around Manhattan, promoting the message that ‘there is a womb’ and ‘one day, you may die and go to the RCOG (or to the other place).’ Although Nan Kempner famously dubbed these advertisements ‘uncontroversial’ [1] a growing number of academic gynecologists were becoming uncomfortable with Apgar’s vision of an afterlife controlled by British administrative staff. They also suspected Dr Apgar of sitting at the centre of an ‘infernal scheme’ in which ‘the mother [was] the automobile factory’ and ‘newborns the illusory Chevrolet.’ These gynecologists [2] believed they could topple Apgar’s dystopia by attacking her most fundamental claim: the existence of the uterus. Together, these heretics formed the Movement of Gynecological Futurists, a movement which we will now discuss (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The uterus (and friends), existence of which was denied by Nillian-Scott.

The Futurists

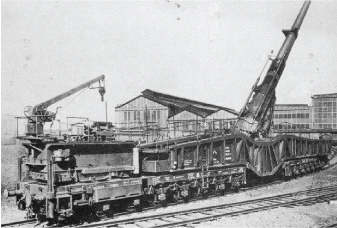

The Futurists held that reproduction was an illusion propagated by a global alliance of powerful midwives, whose vast power and wealth was supported by that ‘deceitful scaffolding of pro-uterine hogwash of which Dr Apgar had been the chief proponent’ (Nillian-Scott, 1974). Contrary to the ostensible implications of their movement’s name, the Futurists held no belief in the future (let alone the afterlife), claiming that ‘this is the only generation that ever was, nor will Virginia Apgar ever be raised from the dead’. Professor Nillian-Scott delivered this excoriating sermon from the pulpit at Apgar’s own funeral, sparking retaliation from the Apgarites, who attacked her followers with building equipment. The Scottite Futurists fought back with hunting knives and a colossal WW1 railway gun nicknamed ‘Lange Ludwig’, leading to a series of bloody skirmishes between the rival schools over the coming months (Figure 2).

Figure 2: ‘Lange Max’, a ‘Lange Ludwig’ prototype from 1912.

The Bloodbath

The battles of the Purists and the Futurists ultimately killed tens of thousands of medical professionals and destroyed the Rockefeller Center. Nillian-Scott boasted that ‘fifty thousand midwives would not be able to rebuild the Rockefeller Center’, but this was to be one of the selfappointed medical cleric’s three failed prophecies. Acting under orders from Apgar’s chief discipline, Lady Hewshott Hawtrey, the Purists oversaw the reconstruction of the complex within three weeks in 1976, surrounding it with fortifications and concrete reinforcements. Then, on the eve of December 1976, Hawtrey projected the image of a giant uterus in the sky. Under its light, she descended on Nillian- Scott’s camp with 40,000 midwives and obstetricians. Hawtrey encircled Nillian-Scott and attacked for eight days, during which Nillian-Scott lost thousands of infantrywomen and the majority of her heavy artillery. ‘I am very unwell,’ said Nillian-Scott on the eighth day, having sustained heavy injuries, ‘and I will be dead as a dog by sundown. But I will not be going to the waiting room of the RCOG.’

With these words, Nillian-Scott entered a patient transport vehicle and drove directly towards the centre of Hawtrey’s front line. Despite despatching thirteen of Hawtrey’s women, she failed to kill Hawtrey, and was thrown from her vehicle onto a medical stretcher. ‘What is this strange sensation?’ said Nillian-Scott. ‘Am I going to die?’

‘No, you will not die,’ said Lady Hewshott Hawtrey. ‘But you are about to go into labour.’

Fifteen hours later, Evelyn Nillian-Scott gave birth.

‘You have given birth to a girl,’ said Lady Hewshott Hawtrey, holding up the newborn child.

‘No I haven’t,’ said Nillian-Scott.

The child was Virginia Apgar again, and recognising the miracle that had happened, Lady Hewshott Hawtrey called off the battle. ‘After three years, our beloved founder had returned from the RCOG,’ she wrote in her memoirs, ‘and that was the end of all our fighting.’

Epilogue, and Concluding Gynecological Remarks

Nillian-Scott refused to acknowledge the existence of her child, claiming that the infant Apgar was ‘a pile of sausages and paperclips and that sort of thing.’ However, some of the leading Scottite Futurists eventually confessed to having ‘doubts about [their] doubts’, and accepted that ‘Virginia Apgar was apparently still alive, though whether she ever died is an intellectual question.’ Members of the rival schools returned to eschatological enquiry.

In conclusion, there may be a uterus, but there is no RCOG. The infant Apgar is now dead, and so we call on RANZCOG to investigate the afterlife with a view to reclaiming her ghost.

There are no references