Journal Name: Journal of Pediatrics and Infants

Article Type:Research

Received date:10 May, 2021

Accepted date:22 September, 2021

Published date:29 September, 2021

Citation:Birner C, Grosse G (2021) Systematic Review on the Efficacy of Interventions for Fear of Childbirth, Anxiety and Fear in Pregnant Women. J Pediat Infants Vol: 4, Issu: 2 (66-90).

Copyright: 2021 Birner C et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited.

Abstract

Background: Fears and anxieties during pregnancy and childbirth are a frequent phenomenon and can have negative consequences on wellbeing, psychological health and birth outcomes. Therefore, it is important to focus on the interventions to reduce those fears and anxieties during pregnancy and childbirth. A systematic review was conducted to examine the current literature on psychological interventions to reduce anxieties and fears during pregnancy and childbirth. Scopus and PubMed were searched from 2015 up until December 2020 for relevant studies. Included were pregnant women, with no restriction on age ranges or parity. Entered in the review were quantitative studies, including randomized controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomized controlled trials as well as treatment evaluations. After reviewing titles, abstracts and studies, 72 studies were included in this review as they met the inclusion criteria. Standard methodological procedures for systematic reviews were used. The quality assessment of included articles was done by using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies (EPHPP).

Results: The main results of this review concern the fear and anxiety reducing effects of psychoeducation, relaxation techniques, guided imagery, supportive care through a midwife, group discussion, “lifestyle based education”, writing therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy groups and stress intervention, individual structured psychotherapy, communication skills training, counselling approaches (except distraction techniques), a motivational interviewing psychotherapy, emotional freedom techniques, breathing awareness and different hypnotherapeutic techniques on different fears and anxieties during pregnancy and childbirth. For mindfulness-based interventions mixed results are found. The effect of an acceptance and commitment therapy, biofeedback interventions, a mind body intervention, mental health training courses, the group intervention Nyytti® as well as cognitive analytic therapy is unclear, due to weak study ratings. Antenatal class attendance reduced delivery fear significantly only in first time mothers. An internet-based problem-solving treatment did not reduce anxiety during pregnancy.

Conclusion: : A broad range of interventions show positive effects on fear of childbirth and fear and anxiety in pregnancy. Further research should address other acknowledged psychotherapeutic practices, like psychodynamic as well as systemic interventions, as they are underrepresented within this review. Furthermore, there is a need for manualized therapeutic interventions, with regards to a combination of effective intervention components.

Keywords: Fear, Anxiety, Childbirth, Pregnancy, Intervention.

Introduction

In the current literature, the prevalence rate of high levels of fear of childbirth is stated as 36.7% in Ireland and in India the prevalence rate of severe pregnancy anxiety levels reached up to 22% [1,2].

Women with very high scores on Fear of Childbirth (FOC) or Tocophobia often suffer under longer birth processes and stronger to unbearable pain compared to women with less fear [2-8]. FOC is reported as one of the most common reasons for unnecessary cesarean sections [2-8]. Compared to women with low levels of FOC, women with intermediate or high levels of FOC seem to have more negative birth experiences [9]. FOC can not only have a negative impact on the birth process, but also influences the wellbeing during pregnancy [10].

There is also evidence for a connection between FOC, postpartal depressions and traumatic stress symptoms [11- 14]. Furthermore, severe FOC or even anxiety may result in pre-term delivery, bonding issues and behavioral/emotional problems of the infant [15-18].

Besides those findings, the current corona pandemic and a resulting increased fear of COVID-19 is a predictor for worries in pregnant women [19]. As possible worries the authors state the “worry about fetus health or mothers’ own health and worry going to hospital” [19]. Molgora and Accordini also stated in their study, that the time of the pandemic has a significant negative impact on the pregnant women’s wellbeing [20].

A number of systematic reviews regarding interventions to treat fear of childbirth exist in the literature of the last five years. There are general systematic reviews and metaanalyses, that list different interventions and their effect on “fear of childbirth” [21-23]. Further systematic reviews focus on pregnancy specific anxiety, as well a mental disorders during pregnancy [24-26].

Besides more general reviews, systematic reviews specifically focussing on mindfulness interventions, psychotherapy interventions, e-health and technology based interventions exist [27-39]. Further meta-analyses focus on the effect of expressive writing, psychoeducation interventions and hypnosis based interventions on anxiety related to pregnancy [40-42].

The reviews of Bright et al., Brixval et al. and O’Connell et al. are not listed as only study protocols were found [43- 45]. The mentioned reviews included studies up to the year 2019.

The present systematic literature review is the broadest and up to December 2020 most recent overview regarding the effects of psychological interventions on fear and anxiety related to pregnancy and childbirth published in the last five years with 72 included and rated studies. While some of the past reviews focused only on certain outcome variables (e.g. only fear of childbirth as a narrow topic) , this present review focusses on broader fears and anxieties regarding the whole pregnancy and childbirth process and therefore addresses a research gap [21,23,46]. This systematic review encloses studies up until December 2020.

The aim of this systematic review was to examine the effect of psychological interventions on “fear of childbirth” as well as fears and anxieties during pregnancy.

Previous reviews stated positive effects of psychological interventions. Hypnosis based, psychotherapeutic interventions and psychoeducation seem to have a positive impact on fear of childbirth [25,42,47]. There is a need to keep those findings updated and an existing research gap to review further interventions stated within the literature.

Definitions

There is no clearly delimitable and common definition of fear of childbirth (FOC) in the literature. It is also difficult to draw a line between subclinical, phobic and pathological levels of FOC [48]. To give an overview over existing terms in the literature, this paper makes an attempt to define different phrases related to the term FOC. This systematic review focusses besides FOC on different anxieties and fears during pregnancy and childbirth.

FOC (Fear of childbirth)

Areskog defined „fear of childbirth“ (FOC) first in a population of Swedish pregnant women as: “a strong anxiety which had impaired their [the women’s] daily functioning and wellbeing”. Later, during the 2000s, a study from Sweden defined FOC as belonging to “the family of anxiety disorders” [49,50].

Klabbers pointed out, that FOC is an anxiety disorder or phobic fear [51].

In the classification of diseases – 10 (ICD 10) fear of childbirth could most likely be listed under code O99.8 as “other specific diseases and conditions complicating pregnancy, childbirth, or puerperium” [52].

Wijma describes “clinical FOC”, as a “disabling fear that interferes with occupational or academic functioning, with domestic and social activities or with relationships”. The symptoms of FOC could be characterised as “worries or extreme fear” [53,54].

FOC has different manifestations. It is “assumed to be a continuum with no or low fear on one end, and severe or extreme fear on the other” and is clinically relevant “if it affects a woman’s quality of life” [23].

FOC can also be classified into primary FOC, which occurs in nulliparous women and secondary FOC relating to women who already had traumatic birth experiences [48,55]. A third form is FOC as a symptom of prenatal depression [51,55,56].

Tocophobia

Primary tocophobia is defined as “severe fear precedes conception and leads to avoidance of tokos (Greek: childbirth)”, while secondary tocophobia is a “phobic fear resulting from a distressing or even traumatising childbirth experience” [23]. It is characterised as an “unreasoning dread of childbirth” relating to women in a “specific and harrowing condition” including a “pathological dread” and “avoidance of childbirth” [56]. Tocophobia is “a specific anxiety or fear of death during parturition precedes pregnancy“ that is “so intense that tokos (childbirth) is avoided whenever possible; this is a phobic state called tocophobia” [57].

Bhatia and Jhanjee defined tocophobia as “a pathological fear of pregnancy” and indicated the pathological aspect of tocophobia, which can result in avoidance of childbirth [54,58]. The authors distinguish tocophobia – similar to the classification of FOC - between primary fear of childbirth, in women without previous pregnancy experience and secondary fear of childbirth related to a “traumatic obstetric event in previous pregnancy” [54].

Tocophobia often is defined by ≥ 85/165 points on the Assessments Wijma Delivery Expectancy Questionnaire (W-DEQ A) [8,59].

A recent systematic review determined tocophobia to be synonymous with severe FOC [59]. Based on this conclusion this present paper also refers to severe/high FOC as synonymous to tocophobia.

Childbirth anxiety (CA)

Wijma and Wijma define childbirth anxiety as follows: “When a woman is afraid of the situation where a child will or is to be born […] CA covers the whole continuum from a little fear that is easy to cope with to phobic fear, when the woman wants to avoid the situation by all means”[60].

Perinatal anxiety (PNA) and perinatal generalized anxiety disorder (GAD)

Harrison, Moore and Lazard characterized the term perinatal anxiety and Misri et al. introduced the term Perinatal Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD), which is defined as “excessive, uncontrollable worry that can cause functional impairment” [61,62].

Further forms of pregnant related anxieties

Pregnancy can be accompanied by a variety of anxiety disorders, like panic, disorder with or without agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, generalized anxiety disorder, specific phobia, social anxiety disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder [18].

Methods

Criteria for considering studies

Papers included in this systematic review were limited to publications in English and German language only with the restriction for publication year between 2015 and December 2020.

Inclusion criteria: The inclusion criteria for this systematic review were outcomes regarding fears or anxieties during pregnancy and childbirth. Different definitions of the concept “fear of childbirth” and the understanding of fears and anxieties during childbirth were admitted. Besides, varying outcome measurements were valid. Pregnant women (primi-/nulli- and/or multiparous as well as primi-/ nulli- and/or multigravida) with no restriction to age ranges were included. The interventions were restricted to psychological interventions, biofeedback interventions, mindfulness-based interventions and midwife counselling studies. Included studies focused on the prenatal period. Only intervention studies were included (no correlation studies about personality traits).

Exclusion criteria: Excluded were study protocols, qualitative studies, reviews, case series designs, case reports, consensus bundles, medical research counsel frameworks, studies with no described study design and uncorrected proof studies. Studies of pregnant women with specific somatic complains, (in)fertility or abortion studies, yoga interventions, pharmacological interventions (including psychopharmacology), music interventions, spiritual interventions, art therapy as only intervention, and aroma therapy studies were excluded. Not included were medical studies, studies on pregnancy loss or sleeping problems, postpartum studies, traumatic birth studies, studies focusing on depression only, sport or physical activity interventions, studies relating to stillbirth, and ultrasound interventions. Studies written in other languages than German or English were also excluded.

Search methods for identification of studies

The electronic databases PubMed and Scopus were searched for articles using the terms “fear”, ”anxiety”, “pregnancy”, “childbirth”, “intervention” from 2015 up to December 2020.

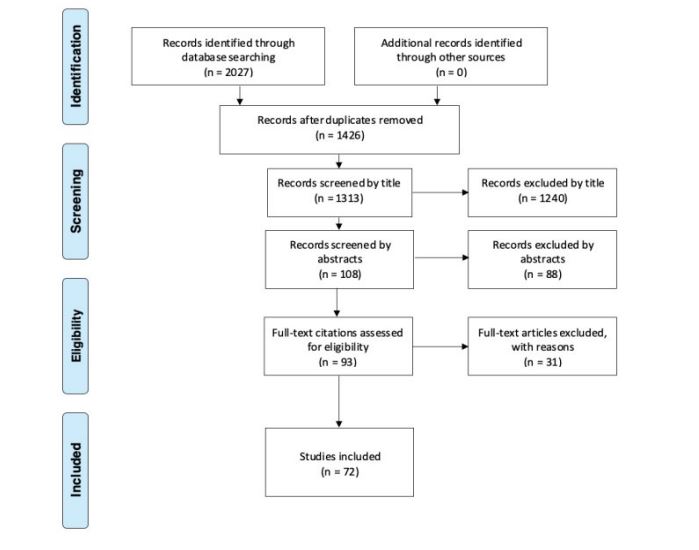

The initial search yielded a total of 3029 studies, after setting the time (year 2015-2020) and language filters a total of 2027 studies were displayed and a total of 1426 studies were screened for this review, after removing all duplicates. Further studies were excluded as they were either not relevant to the review or did not meet the inclusion criteria or were not found. 72 records were screened. See figure 1 for the summary of search item identification. For the final included studies and their results see table 1.

Data collection and analysis

One person was included in the data collection, management and analysis of the studies. No software tools were used to support selection of studies. With an excel programme duplicates were analyzed. No standardized data collection forms were used. The data items are described in table 1.

Quality assessment and risk of bias in included studies

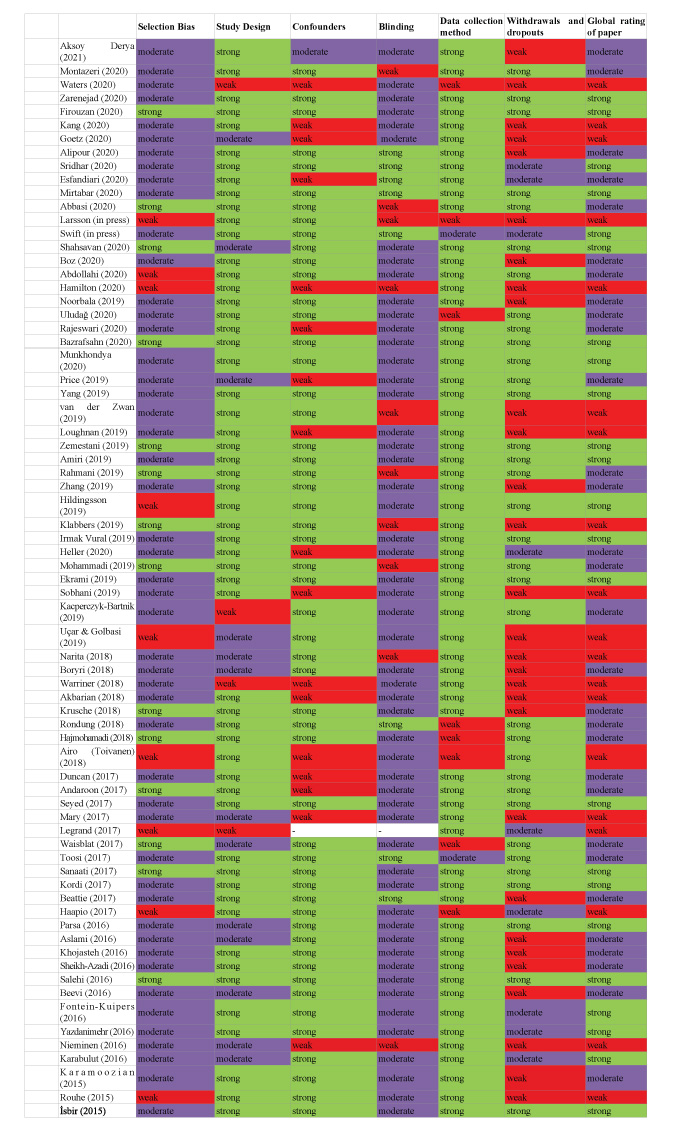

Of the 72 studies included, 22, 31 and 19, respectively, received a strong, moderate and weak rating on the “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies” of the “Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP)”[144]. The risk of bias in the included studies was assessed with this tool. One author was involved in the assessment of risk of bias in included studies. All studies (strong, moderate, weak ratings) were included in the analysis and interpretation. The ratings are listed in table 2.

Dealing with missing data

Few studies without access were excluded from analysis: Nasiri et al., Kao et al., Jahdi et al., Anton and David, Soltani et al., Najafi et al., Hennelly et al. [63-69]. No authors or sponsors were contacted to obtain missing information or clarify the information available. Missing data (e.g. the period of time of data collection) within the viewed studies were marked as such in table 1.

Figure 1:Systematic Review Profile based on the prisma flow diagram [141].

Results

Description of Studies

Characteristics of the included studies

Details of the search results are presented in table 1. 72 studies fulfilled the inclusion criteria, with a total of 8288 pregnant women. The 72 studies were the basis of the findings within this review. The studies were conducted across 18 countries with most studies from Iran (32 studies), second most from Turkey (7 studies) and third most from Sweden, Netherlands and UK (4 studies), China, Finland and USA (3 each), India, Australia and France (2 each), Germany, Iceland, Malawi, Poland, Japan and Malaysia (1 each). Most studies were RCTs, with 47 RCT study designs. The period of time of data collection ranged from 2007 up until 2020.

10 studies included primi- and multiparous women, 7 studies included nulli- and multiparous women, 1 study included nulligravidae and 5 studies primigravidae women. 9 studies included primiparous and 9 nulliparous women. 3 studies included primi- and multigravidae women. 1 study included primi antenatal women. For 27 studies parity or gravidity could not be stated.

Outcome variables

14 studies focused on „fear of childbirth” as an outcome [47,48,70-92].

Some studies focused on “state/trait anxiety during pregnancy”, while others focused only on “state anxiety during pregnancy [92-107].

Some studies had “pregnancy related anxiety as an outcome” and others focused on “anxiety during pregnancy” [96,108-125].

Another outcome was “general anxiety during pregnancy” [126-130].

Few studies focused on specific outcome variables like “mental health of pregnant women – anxiety”, “perinatal mood and anxiety disorders”, “anxiety of pregnant women undergoing interventional prenatal diagnosis”, “labor fear”, “fear of women undergoing labor”, “pain catastrophizing”, “pregnancy worries and stress”, “fear of delivery” and “perceived stress during pregnancy” [131-139].

| First Autor, Year | Country/date of data collection/study design/EPHPP rating | Target population(sample size/age(mean, ± SD)/gravidity and parity) | Intervention/comparators | Study outcome: Interventions Key findings | Measurements (for fear and anxiety during childbirth and FOC) | For this study relevant research topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aksoy Derya (2021) | Turkey 2020 RCT moderate | N=96Age: IG: 28.70 ± 4.73 CG: 28.06 ± 4.12 Not stated | IG: individual teleeducation (interactive education and consultancy provided by phone calls, text message and digital education booklet) CG: No intervention | The posttest PRAQ-R2 total mean scores (t=-4.095, p=.000) of the pregnant women in the IG and CG, as well as the subscales “fear of giving birth” (t=- 3.275, p=.001) and “worries of bearing a physically or mentally handicapped child” (t=-4.354, p=.000) showed a statistically significant difference between the groups. The subscale “concerns about own appearance” did not show a statistical difference between the groups. When the intragroup comparisons of the pre- and posttest in the IG were examined, their “pretest prenatal distress”, “fear of giving birth”, “worries of bearing a physically or mentally handicapped child” and “pregnancy-related anxiety” total mean scores were significantly lower than their posttest mean scores (p<.05). In the CG only the “pretest fear of giving birth” subscale mean score was significantly lower than the posttest mean score (p<.05). |

Pregnancy Related Anxiety QuestionnaireRevised-2 (PRAQ-R2) Revised Prenatal Distress Questionnaire(NuPDQ) | Preg-nancy related anxiety |

| Montazeri (2020) | Iran 2018 RCT moderate | N= 70 Age:IG: 27.5 ± 5.9 CG: 27.7 ± 5.8 Not stated | IG: Three protocolbased writing therapy sessions CG: routine pregnancy care | The results of the independent t-test showed no significant difference in the mean score of preintervention anxiety in the IG and CG (p=.287). According to ANCOVA with baseline score adjustment, the score of anxiety had a significant reduction in the IG compared to the CG (adjusted mean difference: -6.8; 95% confidence interval: -9.1 to -4.5; p<.001). |

Beck anxiety inventory | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Waters (2020) | UK Date of data collection not stated open-label pilot study weak | N= 74Age: 33.5 (3.87) Primi- and Multiparous | 8-week, groupdelivered Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) intervention | At post-treatment, 38 of 55 women (69%) demonstrated a statistically reliable decrease in global distress (d=0.99). |

Diagnoses of moderate-to-severe anxiety disorders were made by the PCMHS team Consultant Perinatal Psychiatrist (SS)(reviewed all routinely obtained clinical data against ICD-10 criteria). Clinical Outcomes in Routine Evaluation– Outcome Measure (CORE-OM) | Perinatal mood and anxiety disorders |

| Zarenejad (2020) | Iran Date of data collection not stated RCT strong | N=70 Age: IG: 27 ± 5 CG: 24.5 ± 5 0 Not stated | IG: received 6 mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR) training sessions CG: routine care | The results of analysis of variance with repeated measures in assessing the changes in pregnancy anxiety score before, immediately after, and 1 month after the intervention showed that the length of time affects the anxiety score of pregnancy by decreasing it (p=.03) and that a significant difference was observed between the two groups in this regard (p=.001). After the intervention, the CG showed significant higher scores in anxiety compared to the IG. |

PregnancyRelated Anxiety Questionnaire | Preg-nancy related anxiety |

| Firouzan (2020) | Iran 2019 RCTstrong | N=80 Age: IG: 26.27 ± 4.48 CG: 25.87 ± 4.58 Nulligravida | IG: face-to-face counselling sessions based on the BELIEF protocol + telephonecounselling sessions CG: prenatal routine care | After adjusting for the pretest scores, there was a significant difference between the IG and CG on post-test scores of W-DEQ-A (F(1,65)=100.42, p=.0001, partial eta squared = .60). The IG got lower scores on W-DEQ-A at post-test than the CG, indicating that the BELIEF protocol was effective in decreasing childbirth fear. |

W-DEQ A | FOC |

| Kang (2020) | China2012-2014RCTweak | N=100 Age: 26.9 ± 1.5 Not stated | IG: psychological intervention CG: Routine Nursing Care | Postoperative SAS scores were significantly lower in the IG than in the CG and the differences were statistically significant (p < 0.01). In the CG, differences in anxiety and fear levels were not statistically significant between preoperation and postoperation (p > 0.05). | Self-rating Anxiety Scale (SAS) | Anxiety of pregnant women under-going interventional prenatal diagnosis |

| Alipour (2020) | Iran2017-2018RCTmoderate | N=54Age: IG: 29.1 (4.3) CG: 29.4 (4.5) Primi- and multiparous | IG: communi-cation skills training package + couplebased intervention CG: two sessions of childbirth preparation + after the completion of the third phase of the study: given educational pamphlets | The level of anxiety three months after intervention was lower (p=.001) in the IG than in the CG. The results showed the impact of group in the level of anxiety (p<.001) was significant. During the study follow-ups in the IG, a significant change in the level of anxiety (p<.001) occurred. |

Questions related to the subscales of depression and anxiety of General Health Questionnaire (GHQ) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Goetz (2020) | Germany2019 prospective pilot study with an explorative study design weak | N=68Age: 32.07 (4.74)Not stated | Intervention: electronic Mindfulness-based interventions (eMBIs) | After completing the 1-week electronic course on mindfulness, the participants showed a significant reduction in the mean state anxiety levels (p<.05). |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-S) PregnancyRelated Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ-R) | Preg-nancy related anxiety State/Trait Anxiety |

| Sridhar (2020) | USA2018Pilot feasability studymoderate | N=30Age: 30.1 (7.4)Not stated | IG: Participants could choose any of the three available virtual reality (VR) environments (dream beach, Iceland, dolphins) CG: receiving standard care | The median decrease in the VAS anxiety score from before to after the procedure was greater in the IG than in the CG (Wilcoxon rank-sum, p=.3324) All but one participant reported that VR was either very effective (53%) or somewhat effective (40%) in relieving anxiety during and after the procedure. |

Modified Amsterdam Preoperative Anxiety and Information Scale (APAIS) + a visual analogue scale (VAS) for anxiety, ranging from 0 (minimum anxiety) to 10 (maximum anxiety) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Esfandiari (2020) | Iran2018-2019RCTmoderate | N=80Age: IG: 27.87(5.26) CG: 23.72(4.27)Not stated | IG: group supportive counseling (SC) CG: antenatal usual care (AUC) | In the IG scores of state-anxiety were reduced more remarkably than in the CG with a large effect size (B=-8.47, p= <0.001, η² = 0.40). |

Spielberger StateAnxiety Inventory (STAI-Y) | State anxiety during pregnancy |

| Mirtabar (2020) | Iran2017-2018RCTstrong | N=60Age: 29.0 ± 5Not stated | IG: received individual structured psychotherapy + preterm labor inpatient medical care CG: inpatient medical care for preterm labor | Both the IG and CG had significant reductions in the mean scores of state-anxiety and pregnancy distress from the baseline to end of study (p<.05). The ANCOVA tests determined that the IG had a significant improvement in the state-anxiety scores compared with the CG (p<.001). |

State-Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State anxiety in preterm laborPreg-nancy distress |

| Abbasi (2020) | Iran2015-2016RCTmoderate | N=153Age: IG Educational software :25.5 (3.8) IG: Educational Booklet: 25.9 (3.6) Control: 25.1 (3.2) Not stated | IG Educational software: studied the educational content of the educational software IG: Educational Booklet: studied the educational content of the educational booklet CG: routine care | The average state anxiety score in the educational software group and the educational booklet group was significantly lower than the CG (p<.001). Also, the mean state anxiety score in the educational software group was significantly decreased compared to the educational booklet group after the intervention (p<.001).The average score of trait anxiety in the educational software group and the educational booklet group was significantly lower than the control group (p<.001). Also, there was no significant difference between the two intervention groups (p=.952) |

State-Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State and trait anxiety during pregnancy |

| Larsson (in press) | Sweden2014- 2015RCTweak | N=258Age (n, %) <25: 14 (10.4) 25-35: 100 (74.6) >35: 20 (14.9)Primi- and multiparous | IG: internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy (iCBT)CG: standard care (i.e. counseling with midwives) | No statistically significant difference in the perceptions of the birth experience, regardless of treatment method for fear of birth. | Fear of birth scale | FOC |

| Swift (in press) | Iceland 2017-2018quasi-experimental controlled trialstrong | N=92Age: IG: 28.3 (5.1) CG: 27.9 (4.4) Not stated | IG: Enhanced Antenatal Care (EAC) CG: usual antenatal care | At baseline, a higher proportion of IG participants (28%) reported high fear (>60 points) compared with women in CG (21%). By T2 fewer women reported high fear of birth in IG (9.4%) compared with CG (15.0%).For the full sample, the mean childbirth fear change score was 7.2 points among women in IG and -3.0 points among women in usual care (p=0.315). Based on Cohen’s criteria the effect of participating in IG on the reduction in mean childbirth fear was small (Cohen’s d=0.21). Restricting the main analysis to women who had not attended classes alongside antenatal care (n = 26) resulted in a large effect size difference in fear change between women in IG and CG (Cohen’s d=-0.83), with a change score of -14.1 points among women in IG and a slight increase in fear among women in CG (1.2 points; p=.003). |

Fear of birth scale (FOBS) | FOC |

| Shahsavan (2020) | Iran2018quasi-experimental studystrong | N=102Age: IG: 28.10 (± 5.20) CG: 28.69 (± 5.31)Nulliparous | IG: Internet-based guided self-help cognitive- behavioral therapy (I-GSH-CBT)CG: normal pregnancy care | The IG intervention could significantly reduce the scores of childbirth fear (p=.002). The fear scores in the CG were significantly increased in parallel with the IG intervention (p<.001). |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Boz (2020) | Turkey2018RCTmoderate | N=24Age: 28.21 (± 4.37)Nulliparous | IG: Psychoeducation Program based on Human Caring Theory in The Management of Fear of ChildbirthCG: Antenatal education classes group | The FOC of women from pretest to posttest was statistically more reduced in the IG compared to the CG (p=.000). |

W-DEQ-A/B | FOC |

| Abdollahi(2020) | Iran2018RCTmoderate | N=70 Age (range): aged 18–50 Not stated | IG: Motivational Interviewing (MI) PsychotherapyCG: Prenatal usual care (PUC) | The total score of W-DEQ declined more considerably in the IG than in the CG between pretrial (T0) and post-trial (T1), with a large effect size (B=−23.54, p<.001, ƞ2 = 0.27). Scores of the six subscales of W-DEQ diminished more substantially in psychotherapy than in prenatal usual care. |

W-DEQSpielberger state anxiety | FOC |

| Hamilton(2020) | UKDate of data collection could not be statedRCTweak | N=39Age: TAU+CAT: 30.2 (6.4) TAU: 31 (2.9)Not stated | IG: cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) plus treatment as usual (TAU)CG: treatment as usual (TAU) | The analysis found no difference in the primary outcome. The STAI scale at 24 weeks after randomization between the groups, with an adjusted difference in means of 6.1 points (95% CI: −4.2 to 16.3) was in favor of CAT for the State domain and 6.2 points (95% CI: −2.8 to 15.2) for the Trait domain. The IG having lower (better) STAI scores at all four post-randomization assessment points than the CG. For the four post-randomization repeated STAI measures, a simple summary measure for each individual patient, the average post-randomization score was calculated. Average post-randomization STAI scores were compared between the two arms (CAT and TAU), again with analyses unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. All the 95% CIs for the difference in mean follow-up scores between the CAT and TAU groups, include zero, which is compatible with no difference in outcomes between the randomized groups. |

Spielberger State/ Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/ Trait Anxiety |

| Hamilton (2020) | UK Date of data collection could not be stated RCT weak | N=39 Age: TAU+CAT: 30.2 (6.4) TAU: 31 (2.9) Not stated | IG: cognitive analytic therapy (CAT) plus treatment as usual (TAU) CG: treatment as usual (TAU) | The analysis found no difference in the primary outcome. The STAI scale at 24 weeks after randomization between the groups, with an adjusted difference in means of 6.1 points (95% CI: −4.2 to 16.3) was in favor of CAT for the State domain and 6.2 points (95% CI: −2.8 to 15.2) for the Trait domain. The IG having lower (better) STAI scores at all four post-randomization assessment points than the CG. For the four post-randomization repeated STAI measures, a simple summary measure for each individual patient, the average post-randomization score was calculated. Average post-randomization STAI scores were compared between the two arms (CAT and TAU), again with analyses unadjusted and adjusted for covariates. All the 95% CIs for the difference in mean follow-up scores between the CAT and TAU groups, include zero, which is compatible with no difference in outcomes between the randomized groups. |

Spielberger State/ Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/ Trait Anxiety |

| Noorbala (2019) | Iran 2015–2018 Clinical Trial Study weak | N=202 Age: 27.92 ± 5.41 Not stated | IG: life skills and stress management training, supportive psychotherapy educational package and drug therapies CG: routine pregnancy treatment | In the investigation of mental health subscales in the IGs and CGs, results demonstrated a significant intergroup difference in the 35–37 week followup in terms of anxiety (p=.003). Anxiety showed a significant decrease in the intervention group compared to the CG. | General Health Questionnaire-28 (GHQ-28) Golombok Rust Inventory of Marital State (GRIMS) | Mental health of pregnant women - anxiety |

| Uludağ (2020) | Turkey Date of data collection could not be stated RCT moderate | N=60 Age: IG: 25.66 ± 4.33 CG: 24.70 ± 4.75 Nulliparous | IG: Philosophy of HypnoBirthing CG: Routine Care | A statistically significant difference was found between the labor fear mean score in terms of group, time and group*time interaction (p<.05). There was a significant difference between the post-intervention, active phase and transition phase labor fear mean score of the groups in terms of the intervention performed: the fear of labor was lower in the IG compared to the CG. |

Visual analog scale of determining the fear and pain of labor | Labor fear |

| Rajeswari (2020) | India 2015-2016 RCT moderate | N=250 Age: Majority were in the age group of 25–29 years (IG 60 [48%]; CG 57 [45.60%]). Primigravida | IG: Routine Care + progressive muscle relaxation CG: routine antenatal care | In the posttest, the groups exhibited significant difference for stress ( F3 =24.81, p<.001) and overall anxiety ( F3 =19.80 with p<.001). After the test, there was a significant reduction in state anxiety ( F3 =17.80, p<.001) and trait anxiety ( F3 =18.60, p<.001) between the intervention and control groups. There was a strong negative correlation between PMR and state anxiety (r = -0.26, p<.001). |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/Trait Pregnancy anxiety |

| Bazrafsahn (2020) | Iran 2019RCT strong | N=72Age: IG: 28.06 ± 4.33 CG: 26.22 ± 4.43Not stated | IG: group educational counseling sessions (integration of psychological instructions and interactive lectures) + routine care CG: routine pregnancy care | There was a significant difference in the mean anxiety score between the IG and CG before the group educational counseling sessions. After this intervention, a significant reduction in the mean anxiety scores of intervened pregnant women compared to the control was found. This decrease in mean anxiety score after the 1-month postcounseling was more pronounced than the 6th week after the study onset (p<.001). Low anxiety scores in the intervention group over time were also maintained. |

Pregnancy-related anxiety questionnaire Short-form PRAQ with 17 items (PRAQ-17) | Preg-nancy related anxiety |

| Munkhondya (2020) | Malawi2018quasi-experimental studymoderate | N=70Age: IG: 19.83 (± 2.90) CG: 20.11 (± 2.70)Primigravida | IG: companionintegrated childbirth preparation (structured childbirth education)CG: Routine care | At post-test, being in the intervention group significantly decreased childbirth fears (β= −.866, t(68)=−14.27, p<.001). |

Childbirth Attitude Questionnaire (CAQ) | FOC |

| Price (2019) | USADate of data collection could not be statedone-group repeated measures designmoderate | N=12Age (median, range): 30.5 (24–40)Nulli- and Multiparous | Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting (MBCP) – online audios | The significant pre-post intervention improvements included a decrease in prenatal pregnancy anxiety (p=.002), and increased interoceptive awareness skills of self-regulation (p=.016) The significant longitudinal improvements included interoceptive awareness skills of self-regulation (p=.04). The effect sizes for these significant improvements were large, ranging from 0.62 to 1.18. |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) | General anxiety during pregnancy |

| Yang (2019) | China2018RCTstrong | N=123 Age: IG: 31.31 (4.97) CG: 30.38 (3.91)Nulli- and multiparous | IG: online mindfulness intervention program (training acceptance for internal and external experiences) CG: routine prenatal care | In the IG, the mean scores of the PHQ-9 and GAD7 before the intervention indicated mild symptoms of anxiety; these scores decreased significantly at the end of the intervention, indicating no symptoms (t=6.218, p<.001; t=5.422, p<.001, respectively). No changes in the PHQ-9 and GAD-7 scores were observed in women in the CG when scores before versus after intervention were compared. Postintervention scores of both PHQ-9 and GAD7 were significantly lower in the IG than in the CG. Additionally, a larger proportion of women in the IG had no symptoms of anxiety after the IG compared with women in the CG. | Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) | General Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Van der Zwan (2019) | NetherlandsDate of data collection could not be statedRCTweak | N=50 Age: 31.6 (5.9) Primi-/Nulli- and Multiparous | IG: heart rate variability (HRV)- biofeedback + Stress-Reducing Intervention (psycho-education + taught abdominal breathing and HRV biofeedback) CG: Waitlist condition | In both conditions anxiety and stress levels were reduced and well-being increased between preand post-test (T1–T2). In the HRV-biofeedback condition, within-group effect sizes were medium, and long-term improvements six weeks after the training (T1–T3) were similar to those at posttest for all outcome measures except depression. Statistically significant long-term improvements in the HRV-biofeedback condition were present for stress and psychological well-being. Effect sizes were larger in the HRV-biofeedback condition than in the waitlist condition on all outcome variables except anxiety. When comparing the treatment effect between pregnant and non-pregnant women (the Condition– Pregnancy interaction), a statistically significant interaction effect for anxiety appeared. Additional analyses showed that HRV-biofeedback was more beneficial regarding anxiety reduction for pregnant women than for non-pregnant women (pregnant women: B=−4.18, t=−2.74, p=.006; non-pregnant women: B=2.55, t=1.99, p=.046). |

Dutch version of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Loughnan (2019) | AustraliaDate of data collection could not be statedRCTweak | N=77 Age: 31.61 (4.00) Primi - and Multiparous | IG: internet-delivered cognitive behavioral therapy CG: treatment as usual (TAU) | The group by time interactions for psychological distress (F(2,53.93)=7.07, p<.01) and anxiety (F(2,54.67) = 6.48, p<.01) were significant. Participants in the IG demonstrated large and superior reductions in distress at post-assessment compared to CG (g(95%CI) = 0.88(0.34,1.43)), and moderate differences at follow-up, although these were not statistically significant (g(95%CI) = 0.52(-0.07,1.10)). The between group differences for anxiety severity were small and non-significant post-assessment (g(95%CI)=0.40(-0.13,0.93)). However, IG demonstrated a moderate to large effect size reduction in anxiety symptom severity at follow-up assessment compared to the CG (g=0.76; 95% CI:0.17,1.35). |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item scale (GAD-7) | General Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Zemestani (2019) | IranDate of data collection could not be statedRCTstrong | N=38Age: IG: 28.63 (3.02) CG: 30.54 (4.15)Not stated | IG: Mindfulnessbased cognitive therapy (MBCT) intervention CG: Did not receiveany intervention; after 1- month follow-up, two psychoeducational sessions were conducted | Results from the mixed method repeated measure (MMRM) indicate greater improvements in levels of anxiety in the IG than in the CG. As to BAI, results indicated a significant effect of time, F=(43.72), p<.0001, ηp² =.62; and a significant time×group interaction, F=(52.68), p<.0001, ηp² =.67. Post hoc comparisons showed that the IG had a significant decrease in BAI scores from baseline to post-treatment and BAI scores remained significantly lower than those of the CG at follow-up (p<.0001). |

Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Amiri (2019) | Iran2018RCTstrong | N=68Age: IG: 26.2 (5.4) CG: 27.0 (5.6)Not stated | IG: Counseling based on distraction techniques for controlling stress, fear and painCG: training about signs and stages of delivery and the appropriate time for a referral to the hospital | There was no statistically significant difference between the two groups before the intervention (p=.117). But in the 36th week of pregnancy the mean score of the fear of childbirth in the IG was less than that of the CG, but the difference was not statistically significant (AMD: 5.4; 95% CI: −2.4 to 13.0; p=.117). There was no statistically significant difference between the groups after intervention (p=.170). |

W-DEQ-A | FOC |

| Rahmani | IranDate of data collection could not be statedRCTmoderate | N=108Age (18-35): IG 1: 24.4 (4.14) IG 2: 26.52 (4.6) CG: 25.6 (4.35)Primi- and Multigravida | IG 1: Peer Education + training bookletIG 2: Discussion Groups + training bookletCG: not described | Significant difference among the 3 groups (p=.007) after 4 weeks of intervention. Further, the Scheffe test showed a significant difference between the peer education and control groups (p=.04), as well as the training and discussion groups with the peer education group (p=.013). The fears decreased in the IG1 and IG2 compared to the CG (p<.007) four weeks after education. |

Widget’s Maternity Fear Awareness Questionnaire | FOC |

| Zhang (2018) | China2016RCTmoderate | N=66 Age: IG: 25.7(2.79) CG: 25.58(2.33) Primi- and multiparous | IG: Mindfulness stress reduction (MBSR) CG: treatment-asusual | The results found a significant interaction between time and condition for anxiety (F=19.30, p<.001, (ƞ² =0.240) Post hoc comparisons showed that the IG had a stronger decrease in STAI from baseline to posttreatment compared to the CG. |

State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/ Trait Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Hildingsson (2019) | Sweden2016- 2017Experimental Studystrong | N=70Age: <32: 29 (41.4) ≥ 32: 41 (58.6)Primi- and Multiparous | IG: Counseling through known midwivesCG: Counseling through unknown midwives | No differences on level of fear in IG (mean FOBS 71.25; 20.41) versus CG (70.83; 21.52). |

Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) | FOC |

| Klabbers (2019) | Netherlands2012-2015RCTweak | N=134Age: IG 1: 32.8 (SD 4.6) IG 2: 31.8 (SD 3.9) CG: 32.6 (SD 5.3)Primi-and Multigravida | IG 1: Haptotherapy (HT)IG 2: Psychoeducation via the Internet (INT)CG: Care as usual (CAU) | In the intention to treat analysis, only the IG1 showed a significant decrease of fear of childbirth, F(2,99)=.321, p=.040. In the as treated analysis, the IG1 showed a greater reduction in fear of childbirth than the other two groups, F(3,83)=6.717, p<.001. |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Irmak (2019) | Turkey2016- 2017RCTstrong | N=120Age: IG 1: 27.29 ± 3.97 IG 2: 27.51 ± 4.65 CG: 27.36 ± 4.19Nulliparous | IG 1:Emotional freedom techniques (EFT)IG 2: breathing awareness (BA)CG: Standard care. | No significant difference in the scores for the W-DEQ-A between the groups (p>.05). However, the difference in the scores for the W-DEQ-B between the groups was significant (p<.001). This difference was due to the high score of the W-DEQ-B of the CG. Both IG1 and IG2 interventions enabled to reduce the level of birth fear perceived at postpartum. There was also a significant difference in the scores for the W-DEQ-B subscales related to worries about childbirth (p<.05). |

W-DEQ Subjective Units of Distress Scale (SUDS) | FOC |

| Heller (2020) | NetherlandsDate of data collection could not be statedRCTmoderate | N=79IG: 32.08 (4.61) CG: 31.94 (4.83)Nulli- and Multiparous | IG: internet-based problem solving treatment (PST)CG: Care as usual | In the IG, affective symptoms decreased more than in the CG, but between-group effect sizes were small to medium (Cohen’s d at T3=0.45, 0.21, and 0.23 for the 3 questionnaires, respectively) and statistically not significant. |

Hospital Anxiety and Depression ScaleAnxiety subscale (HADS-A) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Mohammadi (2019) | Iran2018RCTmoderate | N=60Age: IG:28.18±3.38 CG: 28.63±3.14Not stated | IG: Intervention group attended Benson’s relaxation technique (BRT) and brief psychoeducational intervention (BPI) educational sessions CG: Received no intervention | Significant statistical difference in the IG before and after intervention (p<.001). In the IG, the mean stress and anxiety scores, and total score were decreased significantly (p<.001). The CG did not show any significant statistical differences (p> .05). There was a significant difference between the mean scores of IG and CG (p<.001). In the IG the mean anxiety score significantly decreased (p<.001). |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale-21 | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Ekrami (2019) | Iran2017RCTstrong | N=80Age: IG: 28.5 (7.4) CG: 30.7 (5.4)Not stated | IG: sessions of individual counseling + sessions of group counseling CG: received routine care | The mean (SD) state anxiety score in the IG decreased from before intervention to 4 weeks after counseling; the mean (SD) state anxiety score in the CG increased from before the intervention to 4 weeks after the completion of the counseling. No significant difference between the IG and CG before the intervention in terms of state anxiety score (p=.759). The mean state anxiety score in the IG was significantly lower than on the CG (adjusted mean difference: −7.8, CI 95% −4.5 to −11.1; p<.001) after intervention. The mean (SD) trait anxiety score in the IG decreased from before counseling to 4 weeks after counseling; the mean (SD) trait anxiety score in the IG was increased from before the intervention to 4 weeks after the completion of the counseling. There was no significant difference between the IG and CG before the intervention in terms of trait anxiety score (p=.473). The mean trait anxiety score in the IG was significantly lower than on the CG (adjusted mean difference: −8.2, CI 95%−10.9 to −5.4; p<.001) after intervention |

Spielberger StateTrait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/Trait Anxiety of women with unplanned pregnancy |

| Sobhani (2019) | Iran2017RCTweak | N= 40Age could not be stated.Not stated | IG: Mindfulness Based Stress Reduction (MBSR)CG: unclear | Mindfulness training had a significant effect on reducing anxiety and stress. |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale (DASS21) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| KacperczykBartnik (2019) | Poland2016cross-sectional survey-based studymoderate | N=147Age: 31.5 (±4.8)Primi- and Multiparous | IG: Antenatal classes attendanceCG: No antenatal classes attendance | Women who gave birth for the first time and attended antenatal classes scored significantly lower in the DFS questionnaire (p<.03). No significant differences in the DFS score were observed in case of patients giving birth for the second or subsequent time. Respondents in the IG scored slightly lower in comparison to the CG (p<.90). |

Delivery Fear Scale (DFS) | FOC |

| Uçar (2019) | Turkey2012-2013pretest–posttest experimental designweak | N=111Age: 25.5 (SD 4.2)Primigravida | IG: educational program on coping with childbirth fears based on CBTCG: did not receive any intervention | The post-education W-DEQ-A score was significant higher in the CG compared to the IG (p<.000). No statistically significant difference was found between the anxiety levels of the IG and CG during the active phase of labor, according to the sum of SAI scores (p=.533). |

State Anxiety Inventory (SAI)W-DEQ-A | FOCState anxiety during pregnancy |

| Narita (2018) | JapanDate of data collection could not be statedExperimental Studyweak | N=97Age: IG: 32.4 (± 3.8) CG: 32.7 (± 5.0)Primi- and Multigravida | IG: heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback Intervention (Stress Eraser)CG: women did not agree to practice the method | The W-DEQ scores reduced significantly in women who performed HRV biofeedback (n=18, p<.001), but there was no change in those who did not perform the method (n=20). |

W-DEQ-A | FOC |

| Boryri (2018) | Iran2017Quasi Experimental Studymoderate | N=180Age: 24.54 ± 4.40Primiparous | IG 1: muscle relaxationIG 2: guided imageryCG: Routine care | The scores of delivery fear before the intervention significantly differed in the three groups (p=.01). A significant difference was found between IG1 and IG2 (p=.01), while the other groups represented no difference. However, the mean score of the fear of delivery was significant in the three groups after the intervention (p=.0001). The post-hoc test further indicated a statistically significant difference in the mean scores of childbirth fear between the IG1 and IG2 (p=.0001), IG1 and CG (p=.0001), as well as IG2 and CG (p=.0001). In the IG1 and IG2 fear of delivery was reduced significantly |

Brislin’s questionnaire | FOC |

| Warriner (2018) | UK2014-2015initial pilot studyweak | N=155 (86 women, 69 men)Age (mean): 35 yearsNot stated | IG: ‘MBCP-4-NHS’- Brief four week course (developed from the nine week Mindfulness Based Childbirth and Parenting (MBCP) intervention) | Change in mood pre-to post course showed that all scores improved and were statistically significant for prospective mothers, except for positive pregnancy experience intensity. Anxiety score has reduced to the 'mild' cut-off. |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7)Oxford Worries about Labor Scale (OWLS)Pregnancy Experience Scale (PES)Brief Tilbury Pregnancy Distress Scale (TPDS) | General anxiety during pregnancyWorries about labor Preg-nancy distress |

| Akbarian (2018) | Iran2016RCTweak | N=120Age was not stated.Primiparous | IG: couples (mental health training course; with the partner present), pregnant women (mental health training course without the partner present) CG: routine care | In the pregnant women group and couples group, the average anxiety score of pregnant women after the intervention was significantly lower than before the intervention (p<.001). A significant difference was shown among the three groups after the intervention. After the intervention, the mean anxiety score of the pregnant women group was significantly lower than that of the CG (p=.002) and this score was significantly lower in the couples group than that in the pregnant women group (p=.045). |

Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scales (DASS-42) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Krusche (2018) | UKDate of data collection could not be statedRCTMmoderate | N= 185Age (mean): 32.7Primi- and multiparous | IG: online mindfulness course (‘Be Mindful Online’) - immediate CG: waiting to take the mindfulness course after the baby was born | A pairwise comparisons showed a decrease in anxiety for immediate, [F(1,69) = 18.42, p<.001), η² =.21] (mean difference -3.88) and waitlist participants, [F(1,69) = 14.27, p<.001, η² =.17] (mean difference -2.23). There was a trend for immediate participants to have lower anxiety at T1 compared to waitlist controls, [F(1,69) = 3.15, p=.08, 2 η =.04]. |

The General Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7 | General anxiety during pregnancy |

| Rondung (2018) | Sweden2014-2015RCTmoderate | N=258Age: <25: 37 (14.3) 25- 35: 186 (72.1) >35: 35 (13.6) Primi- and multiparous | IG: Guided internetbased on cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) CG: Standard care group | The reduction in FOB over time was significantly larger in the guided IG group than in the CG group. However, the predicted level of FOB at the estimated due date did not differ significantly (t 1,240,996 =−0.24, p=.81). Hence, when comparing the intervention groups, no difference was observed in FOB in late pregnancy. |

Fear of Birth Scale (FOBS) | FOC |

| Hajmohamadi (2018) | Iran 2014 RCT moderate | N=114Age was not statedNot stated | IG: Psycho-education CG: Not stated | The mean score of depression and anxiety decreased significantly after the intervention in comparison to that before the intervention and that of CG (p<.001). |

Researcher made questionnaire based on the Predisposing, Reinforcing and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Airo (Toivanen) (2018) | Finland2007-2010Randomized trialweak | N = 460Age: IG: 29.8 (± 4.4) CG: 28.3 ± 5.0Primiparous | IG: group intervention Nyytti® (with psycheducation elements, the lifespan model of motivation, practices to support mentalisation and mind–body connection). | FOC decreased statistically significant during the intervention from the baseline (mean=7.60, SD=1.72) to the last session before childbirth (sixth session; mean=4.56, SD=2.42, Wald=230.43, df=6, p<.001) |

W-DEQ-AVisual Analog Scale (VAS) to measure subjective FOC | FOC |

| Duncan (2017) | USADate of data collection could not be statedRCTmoderate | N=30Age could not be statedNulliparous | IG: Short, timeintensive course. Mind in Labor (MIL): Working with Pain in Childbirth, based on Mindfulness-Based Childbirth and Parenting (MBCP) education CG: standard childbirth preparation course with no mindbody focus | Pain catastrophizing dropped by 3.6 points in the IG group and was essentially unchanged in the CG. The time*group interaction was not significant (t = -1.06, p=.30; estimated treatment effect = -3.26 points, 80% CI [-7.3, 0.8]). When the missing data was imputed, the result did not change (t = -.71, p=.48). |

Pain Catastrophizing Scale (PCS) | Pain catastrophizing |

| Andaroon (2017) | Iran2015-2016RCTmoderate | N=93Age could not be statedPrimiparous | IG: face to face individual counselingCG: Usual services | The present study showed that an individual counseling program provided by a midwife basedon a counseling consultant by a midwife based on BELIFE counseling is effective in reducing fear of childbirth in a way that the level of fear of childbirth in primiparous women in the weeks 36–34 of pregnancy in the IG was significantly lower than the CG. |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Seyed Kaboli (2017) | Iran2016 RCT strong | N=62Age:24-18: 19 (30.64) 29-25: 29 (46.77) 35-30: 14 (22.58)Primiparous | IG: counseling for 6 sessions of 90 minutes + routine prenatal care CG: routine prenatal care + instructional package for dealing with pregnancy stresses | The PWSQ score did not differ significantly between the 2 groups before the intervention (p >.05). After the intervention, the mean subscale scores were lower in the IG than in the CG and showed a statistically significant post-intervention difference between the groups (p=.01). These scores suggest the effectiveness of the intervention in reducing pregnancy-specific stress. |

Pregnancy Worries and Stress Questionnaire (PWSQ) | Preg-nancy worries and stress |

| Mary (2017) | IndiaDate of data collection could not be stated pre- test, posttest quantitative research design weak | N=50Age: 64 % of participants in CG and IG were between 24-29 yearsPrimi antenatal | IG: performed selected mind body interventions (Active visualisation with Birth Affirmations, yogic breathing and relaxation) for 4 weeks CG: routine standard hospital care | Statistical findings proved that there was a significant difference in anxiety level among antenatal women who were subjected to mind body intervention than those who were not. |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Legrand (2017) | FranceDate of data collection could not be stated single-subject A (baseline) – B (hypnotherapy treatment) – A’ (return-to-baseline) research design weak | N=1Age: 23 yearsPrimigravida | Hypnotherapy treatment | A statistically significant declining trend in anxiety scores was observed during the hypnosis phase, and anxiety re-increased in the return-to-baseline phase (p<.05). |

State Anxiety Inventory (SAI) | State anxiety during pregnancy |

| Waisblat (2017) | FranceDate of data collection could not be stated longitudinal repeated measures quasi-experimental design moderate | N=155Age: Group S: 44.3 (13.3) Group H: 46.3 (7.1)Not stated | Group S: standard hypnotic communication Group H: hypnotic communication | The mean fear ratings in the Group H participants were significantly lower than that of the Group S participants (p=.001). |

Rating fear of the epidural puncture using the numerical rating scale (NRS) with 0 = No pain (fear) and 10 = Worst imaginable pain (fear). | Fear of women under-going labor |

| Toosi (2017) | IranDate of data collection could not be statedsemi-experimental clinical trialmoderate | N=80Age: IG: 29.0 ± 2.4 CG: 28.7 ± 2.7Primiparous | IG: Relaxation Training (Benson’s relaxation technique) CG: Routine care | No significant difference between the two groups regarding the anxiety score before the intervention (p=.903). A statistically significant difference was observed regarding the anxiety score after the intervention (p<.001). The anxiety score had significantly decreased in the IG (p<.001), but had significantly increased in the CG (p=.033). Thus, relaxation training was effective in reduction of anxiety score after the intervention. |

Spielberger’s statetrait anxiety scale | State/ Trait anxiety during pregnancy |

| Sanaati (2017) | Iran2015RCTstrong | N=189Age: IG1: 28.2 (5.1) IG2: 27.5 (4.9) CG: 27.7 (4.9)Not stated | Lifestyle based education: included issues related to sleep, hygiene, nutrition, physical activity and exercise, self-concept and sexuality IG 1: both women and their husbands received the lifestylebased education. IG2: only women received the lifestylebased education. CG: Routine care | No significant difference on state or trait anxiety was observed between the groups before the intervention (p=.257; p=.137) The mean score of state anxiety 8 weeks after intervention showed a statistically significant difference among the groups (p<.001). The mean state anxiety scores in the IG1 and IG2 were significantly reduced compared to the CG. The mean state anxiety score was also significantly reduced in the IG1 compared to the IG2. The mean post-intervention score of trait anxiety showed a statistically significant difference among the groups (p<.001). Compared to the CG, the mean trait anxiety score was significantly reduced in the IG1 and IG2; however, no significant difference was observed between the two intervention groups. |

Spielberger StateTrait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) | State/Trait Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Kordi (2017) | Iran2015-2016RCTstrong | N=122Age: IG: 23.2±3.6 CG: 24.2±4.4 Primigravida | IG: psychoeducational program for three weeksCG: Routine prenatal care | No significant differences between the groups with respect to the mean pre-intervention FOC scores. A significant difference was observed between the IG and CG in terms of the mean post-intervention FOC scores (p=.007). The FOC score significantly diminished in the intervention group in the postintervention phase (p=.001). |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Beattie (2017) | Australia2014Pilot randomized trialmoderate | N=48Age: IG: 28.9 (5.7) CG: 28.5 (6.4)Nulli- and Multiparous | IG: mindfulnessbased support program (MiPP) CG: pregnancy support program (PSP) | No statistically significant differences between the IG and the CG were shown on perceived stress across the three time periods (p=.82). |

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-10) (PSS) | Perceived stress during preg-nancy |

| Haapio (2017) | FinlandDate of data collection has not been statedRCTweak | N=659Age (%): 18–22: IG: 3.0%; CG: 4.0% 23–29: IG: 48.0%; CG: 47.0% 30–35: IG 44.0%; CG 45.0% 36–40: IG: 5.0 %; CG: 4.0%Primiparous | IG: extended childbirth education (defined as a midwife-led intervention with low medicalization)CG: regular childbirth education | The mothers in the IG had less childbirth-related fear than those in the CG [odds ratio (OR) 0.58, 95% confidence level (CL) 0.38– 0.88]. |

‘Feelings of Fear and Security Associated with Pregnancy and Childbirth’ Questionnaire | FOC |

| Parsa (2016) | Iran2015Quasi experimental studystrong | N=110Age (IG/CG): 18-22: 16.4%/5.5% 23-27: 47.3%/49.1 % 28-32: 29.1%/36.4% 33-37: 7.3%/ 9.1%Nulliparous | IG: counseling sessions based on the GATHER approach CG: not described | Trait anxiety levels of pregnant women significantly changed (were lowered) as a result of intervention (p<.001). However, no significant difference was found in trait anxiety levels of pregnant women in the CG before and after the intervention. State anxiety levels of pregnant women significantly changed (were lowered) as a result of intervention (p<.001). However, no significant difference was found in state anxiety levels of pregnant women in the CG before and after the intervention. |

Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | State/Trait Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Aslami (2016) | Iran2015RCTmoderate | N=75Age: IG 1: 29.4±3.8 IG 2: 27±3.2 CG: 28.6±4.3Not stated | IG1: treatment of mindfulness based on Islamic spiritual schemesIG2: cognitive behavioral therapy groupCG: no course | The significant levels of all tests reveal that between the anxiety of pregnant women in the IGs and CG, at least in one of the dependent variables in the p<.001 level, there was a significant difference. This finding shows that in the aforesaid related variables statistically significant differences are seen between IG1 and IG2 and CG. These findings revealed that both IG1 and IG2 in comparison to the CG led to a decrease in anxiety in pregnant women. The difference between the average IG1 and IG2 in anxiety was significant in the level of p<.001. Therefore, the mindfulness treatment method in comparison with group cognitive behavioral therapy was more effective on the reduction of anxiety of pregnant women. |

Beck anxietydepression questionnaire | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Khojasteh (2016) | Iran2016 RCT moderate | N=75Age: IG1: 22.76 ± 3.85 IG2: 23.76 ± 3.74 CG: 23.92± 4.41Nulliparous | IG1: Massage IG2: Guided Imagery CG: Routine Care | No significant difference before intervention between groups (p.=063). The mean score of anxiety in all three groups had statistically significant differences after the intervention (p<.001). The post-hoc test showed that the IG1 (p.=.000) and IG2 (p=.000) had significant lower anxiety scores compared to the CG, while no significant differences were found between IG1 and IG2 (p=.928). |

Pregnancyrelated Anxiety Questionnaire - revised | Preg-nancy related anxiety |

| Sheikh-Azadi (2016) | IranDate of data collection could not be statedRCTmoderate | N=60Age: IG: 24 (4.388) CG: 25 (4.387)Not stated | IG: Routine pregnancy care + group discussion courses CG: Routine pregnancy care | Mean anxiety score before the intervention was not significantly different between the IG and CG (p=.674). The results showed, that the mean anxiety score of maternal state anxiety was significantly different between the two groups after the intervention (p=.001). It was significantly lower in the IG compared to the CG. |

Spielberger Anxiety Inventory | State anxiety during pregnancy |

| Salehi (2016) | Iran2015 quasi experimental trial strong | N=91Age: 26.04±4.68Nulliparous | IG1: group cognitive behavioral therapy (GCBT)IG2: interactive lectures group (IL) CG: standard prenatal care | There was a significant difference in the level of state and trait anxiety in both the IG1 and IG2 groups before and after the intervention (p<.001). However, there were no differences in state anxiety (p=.330) or trait anxiety (p=.147) in the CG between baseline and 4 weeks later. The results showed significant differences between the 3 groups in state anxiety (p=.011) and trait anxiety (p=.016). No significant difference was found between IG1 and IG2 for state anxiety (p=.079) or trait anxiety p=.069). GCBT and IL significantly reduced anxiety in pregnant women. |

Spielberger’s State-Trait Anxiety Inventory | State/Trait Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Beevi (2016) | MalaysiaDate of data collection could not be stated pre-test/post-test quasi- experimental design moderate | N=56Age: IG: M = 28.23 SD = 3.12 CG: (M = 29.28 SD = 2.65)Nulli- and Multiparous | IG: Hypnosis intervention CG: Traditional antenatal care | There was a statistically significant interaction between the group and time for anxiety symptoms, F(3,126)=7.933, p<.037, partial ƞ² =.16. Results for the simple main effect for group indicated that there was a statistically significant difference in anxiety symptoms at time point 3, F(1,44)=10.764, p=.002, partial ƞ² = .20, but not at baseline, time point 1 and time point 2. There was a statistically significant effect of time on anxiety symptoms for the IG, F(2.138,58.457)=12.352, p= .0005, partial ƞ² =.38 and the effect of time on anxiety symptoms for the CG was not significant, F(3,66) = 0.756, p=.523, partial ƞ2 =.03. Following the significant effect of time for the IG, a pairwise comparison was performed and results indicated that anxiety symptoms were statistically significantly reduced between time point 1 and baseline (M=2.48, SE=0.80, p=.035), between time point 2 and baseline (M=3.91, SE=1.18, p=.020), between time point 3 and baseline (M=6.10, SE=1.27, p=.001), between time point 3 and time point 1 (M=3.62, SE=1.13, p=.026), but not statistically significant between time point 1 and time point 2 (M=1.43, SE=0.89, p=.734) and between time point 2 and time point 3 (M=2.19, SE=0.82, p=.085) |

Depression Anxiety Stress Scale—21 (DASS-21) | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| FonteinKuipers (2016) | Netherlands2013-2015RCTstrong | N=433Age: IG: 30.11 (±4.09) CG: 29.98 (±3.71)Nulli- and multiparous | IG: Wazzup Mama?! focused 1. on the signs and symptoms of maternal distress and identification of the origin of the state of mood 2. identifying stressors 3. measurement of maternal distress. CG: antenatal care as usual | In the CG, the mean STAI scores significantly increased from baseline (T1) to post-intervention (T2) (p<.001, p<.001, p<.001). Mean PRAQ scores increased but did not reach statistical significance (p=0.12). The proportion of STAI and PRAQ scores above cut- off level significantly increased from baseline (T1) to post-intervention (T2) (p<.001, p=.045, p=.03) In the IG, the mean STAI and PRAQ scores were significantly lower at T2 compared to T1 (p=.001, p<.001, p<.001). The proportion of PRAQ scores above cut-off level were significantly lower at T2 compared to T1 (p=.002, p=.009). The STAI scores above cut-off level decreased, but this did not reach statistical significance (p=.4, p=.4). |

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) and PregnancyRelated Anxiety Questionnaire (PRAQ) | State/ Trait Anxiety in preg-nancy |

| Yazdanimehr (2016) | IranDate of data collection has not been statedRCTstrong | N=80Age: IG: 26 (5.82) CG: 26.73 (4.54)Not stated | IG: Mindfulnessintegrated cognitive behavior therapyCG: Routine prenatal care services | The differences between the study groups regarding the pretest mean scores of anxiety were not statistically significant (p<.05). The results showed that at T2 and T3, the mean scores of anxiety in the IG were significantly lower than the CG (p<.001). |

Beck Anxiety Inventory | Anxiety during pregnancy |

| Nieminen (2016) | Sweden2012- 2013feasibility studyweak | N=28Age: 30.5 (24-39)Nulliparous | IG: Internetdelivered therapistsupported self-help program based on cognitive behavioral therapy (ICBT) | Statistically significant (p<.0005) decrease of FOC. The W-DEQ sum score decreased pre- to posttherapy, with a large effect size (Cohen’s d=0.95). |

W-DEQ | FOC |

| Karabulut (2016) | Turkeydate of data collection has not been statedquasi-experimental & prospective studystrong | N=192Age: IG: 28.87 ± 4.54 CG: 25.73 ± 5.35Primiparous | IG: Antenatal educational program (health in pregnancy, birth and breathing exercises, breastfeeding, baby care, post-partum period and family planning)CG: routine pregnancy care and information | The IG’s pre-education and IG’s first measurement levels of FOC showed significant differences (p<.005). The IG’s post-education and CG’s second measurement levels of FOC also showed significant differences (p<.005). According to this finding, antenatal education was effective in reducing the FOC among primipara. |

W-DEQ-A | FOC |

| Karamoozian (2015) | IranDate of data collection has not been stated RCT moderate | N=30Age is not reportedPrimiparous | IG: cognitivebehavioral stress management (CBSM) CG: prenatal care | There is a significant difference in the adjusted average scores of total anxiety between the IG and CG. The effect of pretest was significant with ƞ² p =0.57, p<.01, and f=34.83. As a result, it can be said that CBSM significantly reduced the total anxiety in the IG. |

PregnancyRelated Anxiety Questionnaire | Preg-nancy related anxiety |

| Rouhe (2015) | Finland2007-2009RCTWeak | N=371Age not statedNot stated | IG: group psychoeducation with relaxation exercisesCG: conventional care | There was a significant difference between the groups in mean W-DEQ-B sum scores (F=1.1, df=199, p=.016 Cohen’s d=0.35, small effect size), indicating a more fearful childbirth experience in the CG. Childbirth experience was less fearful in the IG compared to the CG across all modes of delivery, although none of the differences reached significance, potentially because of small sample sizes. |

W-DEQ A+B | |

| İsbir (2015) | Turkey2014RCTstrong | N=72Age: IG: 24.9 (5.9) CG: 25.0 (4.7)Primi- and multiparous | IG: Supportive Care during labor by midwives (physical, emotional, instructional, informational, advocacy support) CG: routine hospital care | The IG reported less fear of delivery during the active and transient phases of labor than the CG (p<.05). |

W-DEQ “Delivery fear scale” | Fear of delivery |

Table 1: Summary of the included studies (Description of Studies).

Figure 2: Ratings of included studies based on the “Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies” of the “Effective Public Health Practice Project (EPHPP)”

Interventions applied to pregnant women

Online vs. offline: Interventions were delivered in two forms: Via the internet respectively online or digital or offline respectively face to face [81,83,87,89,91,95,108,118,126-128,130]. Online “mindfulness based interventions” seem to be effective online/digital [96,126,128,130]. For the offline „mindfulness-based interventions“ results are inconsistent: Several studies find a positive effect, while Beattie et al. did not show a positive effect of mindfulness-based interventions on perceived stress and Duncan et al. did not show a positive result on pain catastrophizing [103,112,121,124,125,129,13 6,139]. This result does not seem to be affected by the weak ratings of the studies from Goetz et al., Sobhani et al. and Warriner et al. [96,121,129].

There are also mixed results concerning the effectiveness of internet based cognitive behavioral therapy. While Larsson et al. and Loughnan et al. did not find a between group effect for internet based cognitive behavioral therapy, Nieminen et al., Rondung et al. and Shahsavan et al. showed significant effects in favour of internet based cognitive behavioral therapy [83,87,89,91,127]. This result has to be interpreted carefully as the studies from Larsson et al., Loughnan et al. and Nieminen et al., were rated as weak [83,87,127].

Fontein-Kuipers focused on identifying (potential) stress factors, problems or difficult situations in the past or present that may contribute to the development of maternal distress plus gave personal feedback regarding questionnaire results in a web-based tailored program [95]. In the intervention group, the mean state anxiety and pregnancy anxiety scores were significantly lower at T2 compared to T1. The proportion of pregnancy anxiety scores above cut-off level were significantly lower at T2 compared to T1 and the state trait anxiety scores above cut-off level decreased, but this did not reach statistical significance.

Categories of interventions: Summarized within this review are educational interventions: psychoeducation, and more general education [74,76,80- 82,85,92,93,108,109,117,131]. Bazrafshan et al, Boz et al., Hajmohamadi et al., Kordi et al. and Uçar and Golbasi found a positive effect for psychoeducation, while the study of Klabbers did not validate this result [74,81,82,92,109,117]. Taking the ratings of Uçar and Klabbers as weak ratings into account, the results could be interpreted as positive effects for psychoeducational interventions [81,92]. Abbasi et al., Haapio et al., Karabulut et al., Munkondhya et al. and Noorbala et al. showed a positive effect of general education, but the study of Aksoy Derya is contrary to this result [76,80,85,93,108,131]. The weak rating of the study from Haapio et al. does not seem to affect this result. One study examined the effect of partly psychoeducational, but mostly physiological education and only found a small effect of education on fear of childbirth, while Rahmani et al. showed that peer education is effective in decreasing FOC in pregnant women [47,76,88].

With regards to relaxation trainings two studies show a positive effect of relaxation techniques like progressive muscle relaxation and relaxation training [99,102].

The included studies show mixed results regarding mindfulness-based interventions and their positive effect on anxiety/fear and stress. While several authors found positive influences, two studies did not show positive effects of mindfulness-based interventions on perceived stress or on pain catastrophizing [96,103,112,121,125,126,128- 130,136,139]. This result does not seem to be affected by the weak ratings of the studies from Goetz, Sobhani and Warriner [96,121,129].

Four studies included in this review examined the effect of hypnotherapeutic interventions. Beevi et al. stated that an hypnotherapeutic intervention has a positive effect on reducing anxiety during pregnancy [116]. Legrand et al. also found a positive effect on decreasing state anxiety and also showed a re-increase in the return-to-baseline phase, but this study has to be interpreted carefully, as only one person was examined and the rating of the study was weak [105]. Waisblat et al. examined the effect of hypnotic communication on fear of women undergoing labor and found that hypnotic communication (communication that focusses on the awareness of the patient towards sensations and images that support relaxation and comfort) was more effective than standard communication [135]. In addition fear of labor was significantly lower in a “philosophy of hypnobirthing” group compared to the control group (received routine care) [134].

Boryri et al. and Khojasteh et al. studied the effect of guided imagery on FOC and pregnancy related anxiety and found a significant decrease of fear of delivery though guided imagery [73,111].

Narita et al. studied the effect of a heart rate variability (HRV) biofeedback intervention on fear of childbirth and found that FOC was significantly reduced in women who performed HRV biofeedback [86]. Contrary to this result, van der Zwan et al., who studied a heart rate variability (HRV)-biofeedback intervention combined with a stressreducing intervention, did not find significant long-term improvements in the HRV-biofeedback condition [123]. But the results on both of those biofeedback intervention studies have to be interpreted carefully due to weak ratings.

Seven studies examined the effect of counselling on anxieties and fears related to pregnancy and childbirth. Seyed Kaboli et al. showed an effect of counselling on reducing pregnancy-specific stress. Another study, that studied face to face individual counselling conducted by a midwife was effective in reducing fear of childbirth [137,72]. Ekrami et al. examined individual and group counselling [94]. The authors found that the mean state and trait anxiety score of the counselling groups were significantly reduced compared to the control group without counselling [94]. In addition Hildingsson et al. found that it does not make a difference if the counselling is done by a known or unknown midwife. Counselling based on distraction techniques did not show a significant difference compared to a control group intervention (training about signs and stages of delivery and the appropriate time for a referral to the hospital) [71,77]. Parsa et al. examined counselling sessions based on the GATHER approach and showed that trait and state anxiety levels were lowered due to the intervention [98]. Esfandiari et al. showed that group supportive counselling scores of state-anxiety were reduced more remarkably than in the CG with a large effect size [104]. Firouzan examined the difference between face to face counselling and telephone counselling sessions and found that counselling based on the BELIEF protocol was effective in decreasing childbirth fear [75].

This systematic review also included studies about different therapy tools. Montazeri et al. showed a significant and reducing effect of writing therapy sessions on anxiety during pregnancy [120]. An acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT) intervention studied by Waters et al. showed a positive effect on global distress, but must be interpreted carefully due to weak ratings [132]. Alipour et al. examined the effect of a communication skills training package combined with a couple based intervention as significantly effective in the reduction of anxiety during pregnancy [114]. A cognitive analytic therapy intervention examined by Hamilton et al. did not show any difference in trait/state anxiety between the randomized groups, but this result has to be interpreted carefully due to a weak rating [97]. Mirtabar et al. examined the effect of individual structured psychotherapy on state anxiety in preterm labor and showed a significant improvement in the state-anxiety scores compared with the control group (received inpatient medical care for preterm labor) [106]. Aslami et al. (2016) studied the effect of a cognitive behavioral therapy group on anxiety during pregnancy and revealed that the cognitive behavioral therapy group in comparison to the control group (no intervention course) led to a decrease in anxiety in pregnant women [115]. This matches the result of Salehi which also studied the effect of group cognitive behavioral therapy (GCBT) on state/trait anxiety during pregnancy [100]. There was a significant decrease in the level of state and trait anxiety in the GCBT group before and after the intervention. A study about a cognitive behavioral stress management intervention showed that this intervention significantly reduced the total anxiety [110].